eBook - ePub

Fundamentals of Theatrical Design

A Guide to the Basics of Scenic, Costume, and Lighting Design

Karen Brewster, Melissa Shafer

This is a test

Share book

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fundamentals of Theatrical Design

A Guide to the Basics of Scenic, Costume, and Lighting Design

Karen Brewster, Melissa Shafer

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Veteran theater designers Karen Brewster and Melissa Shafer have consulted with a broad range of seasoned theater industry professionals to provide an exhaustive guide full of sound advice and insight. With clear examples and hands-on exercises, Fundamentals of Theatrical Design illustrates the way in which the three major areas of theatrical design—scenery, costumes, and lighting—are intrinsically linked. Attractively priced for use as a classroom text, this is a comprehensive resource for all levels of designers and directors.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Fundamentals of Theatrical Design an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Fundamentals of Theatrical Design by Karen Brewster, Melissa Shafer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre Stagecraft & Scenography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Script Analysis for Designers

Theater begins and is grounded in a story. The story, usually created by a playwright in the form of a script, is the foundation for the collaborative theatrical experience; it is the central work that all of the other artists interpret. Stories about human circumstances can be expressed in a myriad of ways, and literary works generally fall into several broad categories such as poetry, prose, essays, fiction, and drama or plays. The structure of a play and a play’s intent are distinct from those in other categories, in that playwrights write plays to be performed, not read. So, reading a play can be a challenging venture. It must be kept in mind that learning to read plays effectively is a fundamental skill for all theater artisans and is vital to successful designing. It is such an important skill, in fact, that beginners should ideally learn how to read a play effectively before embarking on any other study in the theater.

In this chapter, we will explore the physical aspects of a play script. We will learn what to expect when first looking at any play and then ascertain how to acquire the basic skills needed to effectively read plays. Imagination is of prime importance to any theater artist and in this chapter we will discover the essentials of imaginative engagement. We will realize how effective reading and imaginative engagement ultimately work hand in hand with collaboration in the creation of purposeful production concepts and evocative designs for plays.

HOW TO READ A PLAY

Learning to focus on the dialogue, and to visualize the play’s action while doing so, will lead to a successful play-reading technique. Reading the play aloud with friends or attending a first rehearsal or read-through is a great way to learn to focus on the dialogue and visualize the play. When a play is read aloud, we are able to hear it and get a sense of the characterizations and action. Hearing it helps us visualize it. Readers will eventually acquire the ability to do this independently and silently, but in the meantime, if it helps to read a play aloud, then do it!

In order to read a play, aloud or otherwise, one must be able to access the playwright’s words and intent. Part of the challenge of reading a play is the way the dialogue and action are presented, or the formatting of the script. In order to focus proper attention on the dialogue and successfully interpret any script, readers must acknowledge and understand the structure of the script itself, otherwise called formatting.

Script Formatting

Plays or scripts can be found in anthologies, collections of plays, as well as bound for individual sale. Individually bound play scripts can be obtained through a number of publishers specializing in plays, including Samuel French, Inc., Dramatists Play Service, Inc., Dramatic Publishing, Baker’s Plays, Anchorage Press Plays, and Theatre Communications Group, to name a few. Each publisher has a consistent formatting approach they use when publishing plays. For example, Samuel French, Inc. formats the front matter of their scripts as follows:

Page 1: Title page

Page 2: Copyright and licensing information

Page 3: Licensing cautions and special billing requirements

Page 4: Previous/premier production credits

Page 5: Cast list/time/place

Page 6: Blank page

Page 7: Play begins

There may be some variation within this basic structure. For example, authors may include additional notes, dedications, or special thanks with the script. Play scripts included in anthologies will eliminate much of the information regarding previous productions and contractual arrangements. Readers quickly note that publishers pay special attention to the margins, typeface, and the indentations utilized when printing scripts—these choices are usually made to enhance readability and actor usage.

Dialogue

Italicized stage directions precede (or are imbedded in) many lines of dialogue. Some playwrights, such as George Bernard Shaw, include very detailed italicized directions in their plays. However, readers must keep in mind that the italicized directions in many scripts are not the playwright’s words. Often (particularly in plays published in the mid-twentieth century) these italicized directions are a record of stage directions from the original production gleaned from the stage manager’s notes. Experienced theater artisans often totally ignore these italicized references on the first reading because they do not want to be influenced by other productions of the play. Others may read the italicized directions with interest, treating them as adjunct information to the play rather than essential instructions. Whichever the case, beginning play readers will find the formatting (the way the play is typed on the page) very different from prose writing:

ARMS AND THE MAN ACT I

CATHERINE (entering hastily, full of good news). Raina—(she pronounces it Rah-eena, with the stress on the ee) Raina—(she goes to the bed, expecting to find Raina there.) Why, where—(Raina looks into the room.) Heavens! Child, are you out in the night air instead of in your bed? You’ll catch your death. Louka told me you were asleep.

RAINA (coming in). I sent her away. I wanted to be alone. The stars are so beautiful! What is the matter?

CATHERINE. Such news. There has been a battle!

RAINA (her eyes dilating). Ah! (She throws the cloak on the ottoman, and comes eagerly to Catherine in her nightgown, a pretty garment, but evidently the only one she has on.)

CATHERINE. A great battle at Slivnitza! A victory! And it was won by Sergius.

RAINA (with a cry of delight). Ah! (Rapturously.) Oh, mother! (Then, with sudden anxiety) Is father safe?

CATHERINE. Of course: he sent me the news. Sergius is the hero of the hour, the idol of the regiment.

In this example from George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man, the dialogue is interrupted frequently by descriptive text. It is easy to see how the formatting, while helpful and informative, can get in the way of reading the play—especially for beginners. Generally, most plays are presented in this same fashion, with the bulk of the script dedicated to pages of dialogue such as these. Because this formatting can prevent or hinder beginning readers from successfully accessing the continuity and flow of the play, it is vitally important for theater artisans to develop an effectual play-reading technique; otherwise basic information such as meaning, tone, rhythm, and nuance may be overlooked.

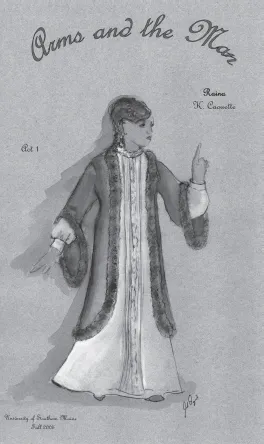

Costume Design for Arms and the Man by Jodi Ozimek for University of Southern Maine.

At the end of the play, when the dialogue pages are complete, most scripts leave the “artistic” aspects of the play and return to more “business” aspects of the script. Samuel French, Inc. refers to this section as “back matters.” Production lists from original productions may be included in the back matters pages of the script. Theater professionals treat these pages much as they do the aforementioned italicized stage directions, often totally ignoring the information or treating the pages as adjunct information to the play rather than primary source information.

Reading Plays—Language and Subtext

We must always keep in mind that, for designers, the essential information in any script is the “art” of the piece: the message, meaning, or theme of the play. That message is not just delivered through the spoken dialogue; it is also delivered by the actions performed by the characters. In order to best absorb the meaning of the play, designers must also learn to become part detective and part psychologist. Characters in a play, like people in real life, do not always say what they mean and often their actions belie their statements. Theater artisans must become adept at reading between the lines, gleaning information not only from the obvious dialogue but from the subtext of the play. For example, in the opening scene of the play Proof by David Auburn, twenty-five-year-old Catherine speaks to her father Robert, who happens to be a famous mathematician.

| ROBERT | Can’t sleep? |

| CATHERINE | Jesus, you scared me. |

| ROBERT | Sorry. |

| CATHERINE | What are you doing here? |

| ROBERT | I thought I’d check up on you. Why aren’t you in bed? |

| CATHERINE | Your student is still here. He’s up in your study, |

| ROBERT | He can let himself out. |

These lines have one obvious layer of meaning that is easily ascertained on first inspection. But, when we discover that Robert is not only mentally ill, but also dead, it gives this dialogue another deeper, richer layer of meaning. It is the subtext that provides the intrigue in this play, and understanding the subtext informs the dialogue and should also inform the design work for any production of Proof.

Subtext refers to the hidden or underlying meaning of a line of dialogue or action. Text is the line of dialogue; subtext is the way that line is spoken, or more specifically, the meaning behind the text. In another example, Yasmina Reza’s God of Carnage is a play that is very dependent on subtext. In this play, there are four characters, consisting of two married couples. We learn very quickly that these couples are the parents of two eleven-year-old boys, who recently got into a violent altercation in a city park where one boy attacked the other with a stick, knocking out his teeth. Reza’s play finds the four parents meeting together at the home of one of the families in an effort to discuss the brutality of the attack. The dialogue begins very collegially, at least on the surface. Through the course of the play we discover that the children are products of their own environments, as many truths and secrets are revealed about all four people and their marriages. Though the characters behave in a civil manner at first, the play ends much less civilly, even violently, as it becomes evident in Reza’s dialogue that profound tensions run deep in the lives of all four characters.

| MICHEL | I don’t think she needs any. |

| VERONIQUE | Give me a drink, Michel. |

| MICHEL | No. |

| VERONIQUE | Michel! |

| MICHEL | No. |

| Veronique tries to snatch the bottle out of his hands. Michel resists. | |

| ANNETTE | What’s the matter with you, Michel?! |

| MICHEL | All right, there you are, take it. Drink, drink, who cares? |

| ANNETTE | Is alcohol bad for you? |

| VERONIQUE | It’s wonderful. |

| She slumps. |

As in the plays Proof and God of Carnage, or when considering subtext in any play, the crux is to determine what the characters are doing, how they are doing it, why they are doing it, and the consequences of their actions. The ability to gather and assess information from any script comes with practice and sensitivity and is necessary to effectively read and interpret plays for the stage.

The best way to further develop the ability to access information from plays is to read more plays! The more plays one reads, the more informed one becomes with the various styles and structures. Some scripts are more challenging to read than others. Many designers state that the more challenging plays to read or access include the following:

• Plays written in verse (elevated language)

• Musical theater pieces

• Theatre of the Absurd or avant-garde pieces (non sequitur language)

• Plays with overlapping dialogue and/or actions Plays with mostly action and little dialogue

• Nonscripted ”concept” or devised pieces

If the dialogue in a play is written in verse or elevated language, the complexity of the language may sometimes make reading and understanding the play more difficult. Classical works by playwrights such as Shakespeare or Euripides or even American musical song lyrics contain unconventional and unrealistic methods of communicating characters’ thoughts and feelings, and take a bit more skill and patience to decipher. The reader must be mindful not to let the poetic form or archaic word usage get in the way of retrieving meaningful information about the story, but instead see the form itself as a revealing stylistic technique. Scripts with complex language or unfamiliar styles may require several additional readings in order for the nuance to become clear.

Musical theater pieces are particularly difficult to visualize when reading because of the diminished emphasis on dialogue and a significant emphasis on song and dance. For example, when the music and lyrics are removed from a musical theater script, what is left is the dialogue, known as the book or libretto, and it can be very thin. There is an emphasis on dance, movement, or action in musical theater that can be time-consuming when actually performed on stage, but can take very little space when typed into a play script. In the modern “book musical,” the lyrics are an essential part of the script and give vital information about character and storyline. Designers must become very adept at piecing together information from the many methods of delivery (dialogue, song lyrics, and stage directions) when visualizing the intent of the composer, lyricist, and playwright.

There are even scripts, such as works that are categorized as Theatre of the Absurd, where dialogue is purposefully enigmatic and nonsensical. Reading these scripts is particularly challenging and demands an open mind and a vivid imag...