![]()

Part I

Before Jutland

![]()

1

British Strategic Planning

Of all the decisions which shaped the conduct of the naval war in the North Sea, by far the most important was that taken by the British Admiralty only a month before the outbreak of war. On July 3 1914 the war plans issued to the Grand Fleet restated the general policy on which they were based, but also introduced a fundamental change to the strategy to be pursued.

The basic policy was stated in terms which reflected its gradual evolution over a number of years:

The general idea is primarily to ensure the destruction of the enemy’s naval forces and obtain command of the North Sea and Channel with the object of preventing the enemy from making any serious attack upon British territory or trade or interfering with the transport of British troops to France should the situation necessitate their despatch. Until the primary object is attained, the continual movement in the North Sea of a fleet superior in all classes of vessels to that of the enemy will cut off German shipping from direct oceanic trade, and will as time passes inflict a steadily increasing degree of injury on German interests and credit sufficient to cause serious economic and social consequences. To prevent or counter this Germany may send a force into the North Sea sufficient not only to break up the Squadrons actually employed in watching the entrances, but also to offer a general action. Germany may also in combination with the above attempt raids upon our coasts by military disembarkations.

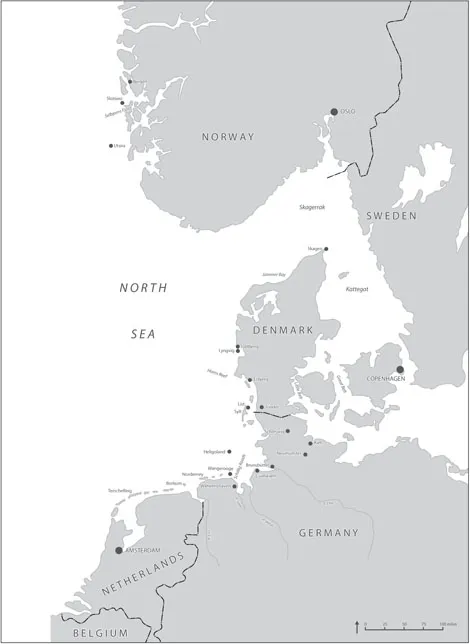

What was significant about the new plans was that they finally gave up the notion of an observational blockade, which had been gradually introduced into Admiralty thinking between 1888 and 1904 in substitution for the policy of close blockade on which strategy had previously been loosely based. An observational blockade had involved the principle of patrolling a line from South West Norway to a point midway between Britain and Germany roughly level with Newcastle on Tyne, and then south to the Dutch coast. The Grand Fleet was to remain to the west of this line. Following the incorporation of this idea into the war plans, there arose serious misgivings about its efficacy. The line was nearly 300 miles long, and it was doubtful if it could really be watched effectively day and night, or that it could be properly supported if the Germans launched an attack, while it would require the employment of very many cruisers and destroyers required elsewhere.

Instead, the Grand Fleet would now be based in northern waters, probably at Scapa Flow, while the Channel Fleet would effectively close the Straits of Dover. In this way the only two exits from the North Sea would be blocked to the German fleet. The war plans set out the Grand Fleet’s task, and explained the reason for the change:

As it is at present impracticable to maintain a perpetual close watch off the enemy’s ports, the maritime domination of the North Sea, upon which our whole policy must be based, will be established as far as practicable by occasional driving or sweeping movements carried out by the Grand Fleet traversing in superior force the area between the 54th and 58th parallels … The movements should be sufficiently frequent and sufficiently advanced to impress upon the enemy that he cannot at any time venture far from his home ports without such serious risk of encountering an overwhelming force that no enterprise is likely to reach its destination.

As Professor Marder has pointed out, the new plans removed at a stroke one of the most significant means available to the Germans of gradually reducing British superiority by the attritional opportunities afforded by a blockade. The German Naval Staff had certainly worked out that the British would move away from the principle of a close blockade; but they still counted on the probability that a distant blockade and close blockade ‘would alternate or merge frequently into one another as the situation changes’:

It is very probable that during the first days of the war, when attacks on our part may be expected, our waters will be closely blockaded … also when it is intended to transport the Expeditionary Force to the Continent.

The consequences of a British decision to conduct only a distant blockade was remarked upon by Admiral August von Heeringen, the Chief of Admiralty Staff, when he observed in 1912:

If the English have really adopted a wide blockade, then the role of our beautiful High Seas Fleet could be a very sad one. Our U-boats will have to do the job then!

The policy of trying to shut up an enemy in his ports went back a long way. In the Seven Years War, and again in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the British fleet maintained, with varying success, a blockade of key French naval bases. It was these operations more than anything else which prompted Admiral Mahan’s famous observation: ‘Those far distant, storm beaten ships, upon which the Grand Army never looked, stood between it and the domination of the world.’

By the 1880s, of course, there had been huge technological developments. Steam propulsion, long range gunnery, the torpedo and the mine had completely changed the environment in which any blockade of any kind could be maintained, and it was argued by many that the concept of blockade had become wholly obsolete as a means of neutralising an enemy fleet. In fact, however, the policy of conducting a close blockade was not entirely abandoned by the British Admiralty as a viable strategy even after 1887, when naval manoeuvres began to demonstrate the difficulties which now existed.

In his brilliant and detailed analysis of the development of British strategy in the three decades before the outbreak of the First World War, Shawn T Grimes has pointed out that the evidence that close blockade was no longer considered feasible ‘is not that definitive’. The problems of maintaining a blockade were still being constantly examined in annual naval manoeuvres. In fact, what the Naval Intelligence Department, founded in 1887 and effectively for many years the centre of naval war planning, evolved was the principle of maintaining an observational blockade. This was to be based on the establishment of advanced flotilla bases, and would fulfil the Admiralty’s primary objectives of defeating the enemy’s fleet, preventing invasion and defending the trade routes. By 1896 this policy was seen as the primary means of meeting the threat posed by the French ‘Jeune Ecole’ strategy of commerce raiding; later it was to be applied to the case of war against Germany, as that possibility gradually became the more likely contingency.

This policy naturally required an emphasis on the effectiveness of torpedo craft. A war plan produced by the Naval Intelligence Department in July 1904, assuming a war with France provided for three formations consisting of the new Scout class cruisers, torpedo gunboats and destroyer flotillas to be based at Falmouth, Portland and Dover, serving as inshore squadrons keeping watch on Brest, Cherbourg and Dunkirk. Manoeuvres in August 1904 tested the plan; although these were too short to produce a definitive conclusion, it was argued by many of the senior officers involved that these manoeuvres had demonstrated ‘that the close blockade and observation of an enemy’s ports were extinct.’

Although historians have disputed the precise point of the Admiralty’s recognition that it was Germany and not France that was the more likely adversary, the 1904 manoeuvres showed that France was still perceived as a most serious threat. Thereafter, the focus shifted. The NID had, by 1902, already started looking at the conditions that would exist in the case of war with Germany. Early planning for this contingency was based around an offensive, inshore, observational blockade, together with combined operations against the German North Sea and Baltic coasts.

The continuous review by the Admiralty of the correct strategy to be followed in the event of war against Germany took place, during the decade before it broke out, against a background of vigorous intellectual dispute. This, fundamentally, resolved itself into the question of whether to adopt an offensive or a defensive strategy. The former view was based to some extent on the influential teachings of Admiral Mahan, who drew from his studies of the influence of sea power the conclusion that attack was the best form of defence. He laid down the principle on which naval strategy should be based in the first of his great books on the influence of sea power:

It is not the taking of individual ships or convoys, be they few or many, that strikes down the money power of a nation, it is the possession of that overbearing power on the sea which drives the enemy’s flag from it, or allows it to appear only as a fugitive; and which by controlling the great common, closes the highways by which commerce moves to and from the enemy’s shores. This overbearing power can only be exercised by great navies.

It was, he argued, the decisive command of the sea that was of prime importance; the attainment of this meant that the purpose for which a navy existed was above all an offensive purpose. This being so, it was a key feature of his philosophy that the fleet was never to be divided or dispersed, but must be concentrated where it could best strike a decisive blow at the enemy. Its first duty was always to seek out and destroy the enemy; the corollary of this was that in respect of blockading operations these must be conducted as close as possible to the enemy’s coast.

A different view was put forward by Julian Corbett. Unlike Mahan, he was not a naval officer; his civilian background meant that his views did not always carry conviction to the minds of traditionalist naval officers. Nevertheless, Corbett had become a very talented and authoritative naval historian. He was recruited by the Admiralty to teach at the War Course, where he was able to develop his conclusions as to the principles of naval strategy. His audience, consisting largely of captains, appears to have been not altogether receptive. Donald M Schurman, in a paper written for a conference held in 1992, has observed that ‘when Corbett showed that the real significance of a historical event might be more appreciated by someone other than a naval officer, they felt threatened or patronised.’

However, Corbett enjoyed the support and respect of Sir John Fisher, and by 1906 he was serving as a member of an ad hoc sub committee under Captain George Ballard, the task of which was to draft the Naval War Plans. Five years later, Corbett set out his fundamental principle in Some Principles of Maritime Strategy:

The object of naval warfare must always be directly or indirectly either to secure the command of the sea or to prevent the enemy from securing it.

He went on to emphasise the alternative:

The second part of the proposition should be noted with special care in order to exclude a habit of thought, which is one of the commonest sources of error in naval speculation. That error is the very general assumption that if one belligerent loses the command of the sea it passes at once to the other belligerent. The most cursory study of naval history is enough to reveal the falseness of such an assumption.

The alternative objective which Corbett thus put forward at once marked out his departure from Mahan’s position. This defensive option was at odds with the views of many naval officers, who saw the next naval war in terms of major battlefleet confrontation. This, indeed, was hardly surprising; their entire professional upbringing, steeped in the tradition of past victories, was heavily reinforced by the building of bigger and better battleships, the function of which was to destroy an enemy. When, in the United States, naval war planners quoted in 1911 with approval a passage from Corbett’s England in the Seven Years War, Mahan was quick after reading it to express his disagreement with views which suggested that taking the offensive at all times was ‘not to show vigour but to play stupidly into the enemy’s hands.’ Anything which qualified the importance of an offensive strategy was anathema to Mahan and to those who accepted his basic propositions.

The fact that Corbett was to a certain extent a protegé of Fisher did not mean that he approved of Fisher’s approach to strategic planning. The First Sea Lord was very much given to grandiose statements about the first duty of the Royal Navy in wartime, and Corbett sought in the introduction which he wrote to the report of the Ballard Committee to apply a corrective:

For the purpose of forming war plans it must always be remembered that when we state the maxim that command [of the sea] depends on the battle fleet, we are stating the conclusion of a logical argument, the initial steps of which are highly important and cannot be ignored. The habitual oblivion of them frequently leads to false strategical conclusions ...Again when we say that the function of the battle fleet is to seek out and destroy the enemy’s battle fleet, although we are stating what is usually true, we are not helping ourselves to a logica...