Christmas in Digby County

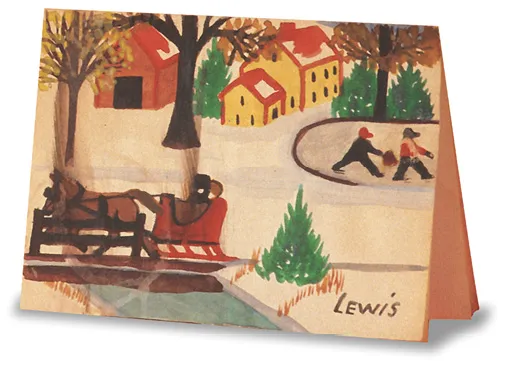

Maud Lewis loved to paint horses and oxen at work, and her home counties of Yarmouth and Digby were among the last places in North America where these working beasts could still be seen on the roads and in the fields and woods. Like the people, they had a special dress for holidays, and as the daughter of a harness-maker, Maud knew well how pretty and attractive this dress was. The horses themselves, the great Clydesdales and Percherons, were not decorated with bells or yokes for the holidays. Instead, their harnesses carried sleigh bells, “silver bells,” and their sound was lighter and brighter and more musical than the sound of the bells worn by the oxen. These bells decorated the teams pulling even the most humdrum logging sledge. On a Christmas tree expedition you could tell what was coming around the next corner by the sound that preceded it.

The oxen on the snow-choked roads were much slower than the horse teams but much stronger, as they proved at the summer fairs. Despite their great weight and strength, they seemed placid, resigned to life. Whether a family would chance upon an ox team during a Christmas tree expedition had to do with the weather. A man might cut his wood in the summer or fall and leave it in the woods to dry before bringing it home. Once the snow had fallen, the first snow of winter, the logs could more easily be skidded out to the roads. It was not unusual for the snowfall to be as late as Christmas, nor to see some bringing home their winter’s wood while others were out looking for their holiday tree. If the teamster was in good spirits he would allow children to pat the big beasts’ snuffling and sniffing noses, from which the steam would rise in the crisp air. A lucky child might get a lick from an ox’s rasping tongue.

Leaving the well-travelled country roads for the wooded roads lined with maple, birch, oak and fir and spruce, an expedition stood a good chance of seeing many of the deep woods citizens Maud Lewis painted: the scurrying rabbits, the ambling, shuffling porcupines. The quiet deer stayed perfectly still until, certain of discovery, their nerve broken, they silently bounded over the fence and flicked into the dark of the woods like Saint Nicholas’s reindeer, to the top of the porch and the top of the wall and into the Christmas night.

Everyone knew that bears ought to be in bed by Christmas time, but it was felt wise to be aware of them. They are the shyest animal in the woods, and generally nocturnal, but so common in the Digby County of Maud’s time that there was a bounty on them; they were said to be hard on the farmers’ sheep, in the same way that hawks were said to raid chicken coops. It was difficult for a child to chop down a Christmas tree without thinking the noise might awaken some slumbering bear, a preoccupation that did not improve the unskilled use of the axe and saw. This amateur gnawing of a tree, however, would certainly have alerted every blue jay, crow and raven in the neighbourhood, and these vigilant ones would have warned every deer, rabbit and bear to stay well away.

Maud decorated the horn tips, bells, and harnesses of these oxen with gold paint.

In Digby, once the Christmas tree was up, it was time for dispersed friends and relatives to return home for the season. As well as seamen on the gypsum boats, and fishermen on the scallop boats and offshore draggers, and lumberjacks in the interior camps, there were students away at college to be ransomed home. Old girls whose marriages had taken them away returned, now widowed, to spend a Christmas like their childhood Christmases with their old sisters. There were young men and women working in Ontario factories and on construction jobs in Quebec, and it was their strongest desire to come home for the holidays. The return home for Christmas was a mark of how well things were going. It was considered a terrible thing if one could not get home, somehow, and whatever else one could hide about the situation, not turning up for Christmas was cause for comment and alarm. The conclusive evidence, indeed disgrace, was having to be sent for.

Many former townspeople came home for Christmas on the last few sailings of the SS Princess Helene. This is the steamship to be seen in Maud’s paintings, with a big black smoky funnel, steaming through Digby Gut. This beautiful steamship no longer runs from Saint John, New Brunswick, to Digby, Nova Scotia, across the Bay of Fundy; when last heard of, the Princess had been sold to a Greek company for a route in the Mediterranean. Yet in the 1950s it was considered by all, it was a fact that no one would argue, that the Princess Helene not only carried the most beautiful name, but was the most beautiful steamship ever to grace the Fundy line.

At Christmas there would be a big crowd on the Long Wharf, all dressed as heavily as Russian infantry, waiting for hours to greet their arrivals. Everyone dressed in overcoats, and in truth there were not a few who had been in the Southwest Novas or the North Novas or the Black Watch and had kept their old army greatcoats. In Maud’s time the last great war was a recent memory, and those army great-coats were in many cases the best their wearers had ever been blessed with. The richer ladies wore furs, the poorer cloth, and most of them a bit of both. Everyone wore hats then, the doctors and lawyers sporting fedoras with creases in them and little colourful feathers in the hatbands, and the workmen cloth caps made in Newfoundland; and below and about the hats long scarves, ranging from cashmere scarves bought at Wright’s and imported from Scotland to home-knitted woollen rigs that could twine twice around your body, let alone your neck; and mittens and gloves. The most distinctive mittens in Digby were the rough three-fingered lobster fishermen’s mittens, made from the wool of sheep raised on the outlying islands off Digby Neck. They were famously warm because it didn’t matter how wet they were: you could pull a hundred lobster traps by hand and still they were proof against the cold waters of the Basin and the whistling winds. It was funny to see everybody on the Long Wharf, not only dressed up but overdressed, a joyous occasion for all strata of the town. Only the taxi drivers were a little upset, what with everyone who owned a car parking it as near as they could to “the boat” and fewer fares than one would expect for all this crowd. The Long Wharf was jammed with chubby, boxy Fords and Chevs, it being the only time of the year when there could possibly be a traffic jam in such a little town as Digby.

The Princess Helene steaming through Digby Gut.

Meeting relatives arriving on the night sailing was more of a magical scene than a merry one. There were fewer attendants on the wharf. Those waiting huddled together, exchanging information on their returning children — “No no! He’s doin’ good!” “Yes yes! She got her course!” — who it might be they were waiting for, how they were doing, what was the latest on the weather outside Digby Gut and on the bay. The dark-as-night water of the basin, the sounds of the waves about the pilings, the expectancy in the dark and cold, with all the nervous looking out to sea past the lighthouses and wishing to be the first to spy the sparkling lights of the Princess, stranger than any star, which somehow appeared pale and quivering, like doused sparks at a forge, and winking like a constellation, and wavering like a candle, until her lights were cried out, and she advanced like a cathedral, like a country fair at night — all this was far more powerful and wonderful than the daytime arrivals. And if the winds and tide were not right for docking, the Princess came in anyway, the best she could, smacking the timbers of the Long Wharf with such a thump and shivering of the buttressing planks the crowd was afraid and wished themselves off the wharf and a hundred and twenty feet west on dry land. Occasionally the Princess made such a poor approach, due to the capricious swirls of the currents, that two or three passes at the wharf were needed before the deckhands could fire the steel ball over our heads to be tied up at the bollard, the throwing line knotted to a hawser so big and thick it could have been a python, with the crowd going Ah! if the deckhand’s throw was good, and Oh! if it was short and landed in the water. Then it had to be hauled out and tried again, bringing the fear that the Princess might not be able to tie up at all but be forced to stand off, bow to the wind, until the tide and wind were right. But with this last successful toss the line was caught, the hawser hauled, and the Princess secured. The tides in Digby were so enormous, forty feet and more of a vertical rise, that when your friends and relations came down the gangplank they seemed to walk straight up if the tide was out, or straight down if the tide was in.

Relations coming by train were met at the station in the centre of town, although the train came through the heart of town to the Long Wharf as well. It was a source of income for young entrepreneurs to carry bags from the train station to the Long Wharf, or from the Long Wharf to nearby hotels. In the summertime the last half-mile on the train from the country to the station was one long garden of flowers; in the winter the approaches were rather bleak, except for the anticipation of wondering who might be at the station to greet and meet. There was an overhanging roof at the station, built “a purpose” as shelter, and it was under this covering that everyone stood (it was too wet to sit on the benches; there was a fire in the stove in the waiting room but no one but old ladies went in there) to listen for the whistle warning at the edge of town, where the tracks crossed the highway. One spectacular day before one well-remembered Christmas, the huge, black, big-boilered monster of a steam locomotive jumped off the tracks in the middle of town, landing on its side like some stricken, steaming dragon. The ice had built up on the steel rails, and the bed had heaved in the cold. Had the dragon fallen to the east it would have landed in the living room of Aunt Jim MacNutt, mother of the famous Bucky MacNutt and wife of the painter Boob MacNutt, but it fell west, and no one was hurt, and the red-and-black passenger cars stayed erect. The travellers were able to walk to the station, a few hundred yards. It was great entertainment for the season, as good as a hockey game, much better than a fudge sale, to watch the men at work, to see the locomotive lifted to its wheels by the construction crane and its fierce grinding and surging up the railroad ramp guiding it on its ride back to the rails. This story was told again and again, Christmas after Christmas, until the station and the Long Wharf and the whistle at the edge of town and the lights on the water became things of the past. To see the Princess now or the old aunt’s arrival at the station or the delivery of Christmas present...