![]()

Chapter One

Indian Shore

Someone looking and idly turning his head, saw the low lines of the whole world—pale horizon, vapory sky, wide-shadowed green sea, the mist-white shore … and the powdery browns of the people moving at what they did.

Paul Horgan,

Great River, 1954

On the eve of the American Revolution, a Philadelphia-born naturalist named William Bartram entered British East Florida and made his way toward the Gulf Coast. This was Seminole country, and Bartram dutifully met with one of their chiefs to ask if he could travel the area freely and gather plant specimens. The chief was bemused at the thought of this thirty-five-year-old white man struggling through swamps and bogs in search of harmless botanical wonders, and promptly dubbed him “Pug Puggy,” meaning “flower hunter.” Happily, permission was granted, and Bartram subsequently wrote almost as much about the Seminoles he encountered as the otherworldly flora and fauna.1

Their name comes from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning “untamed” or “wild.” They were mostly Creek Indians who had moved south from Georgia and made a new life in Florida’s swamps and woods. Bartram liked them at once. “The visage, action, and deportment of the Siminoles,” he wrote admiringly, “form the most striking pictures of happiness in this life; joy, contentment, love, and friendship, without guile or affectation.” The young men were colorful to behold, “all dressed and painted with singular elegance, and richly ornamented with silver plates, chains, &c. after the Siminole mode, with waving plumes of feathers on their crests.” They warmly welcomed this peculiar stranger into their midst, clasping his hand, laughing frequently, sharing game, and exchanging stories around crackling campfires.2

Bartram established himself at Talahasochte, a small village on the banks of the Suwannee River twenty miles from the Gulf. It consisted of a trading house, several dozen log cabins, and a large council house. The cabins were roofed with cypress bark, measured about thirty by twelve feet, and had two rooms, one a kitchen and the other a bedroom. Twenty yards distant from every dwelling stood a “chickee,” a covered platform reached by a short ladder, “a pleasant, cool, airy situation,” where the owner generally received guests. Despite its small size, Talahasochte was a busy place, and while there Bartram observed steady river traffic. The Seminoles traveled by “large handsome canoes,” he wrote, “which they form out of the trunks of Cypress trees, some of them commodious enough to accommodate twenty or thirty warriors.” Typical journeys included forays to the seacoast and, amazingly, all the way “to the point of Florida, and sometimes across the gulph, extending their navigations to the Bahama islands and even to Cuba.” Few Europeans at the time would have dared venture into the open Gulf without a vessel featuring a keel as well as more beam and freeboard than a narrow log canoe. Yet the Seminoles did so routinely. During his short stay Bartram witnessed “a crew of these adventurers” glide upstream and nose into the bank, their cargo “spirituous liquors, Coffee, Sugar, and Tobacco.” One of the paddlers gave the naturalist a tobacco plug reportedly from the Cuban governor himself and explained that in exchange they had taken deer hides, dried fish, honey, and bear oil.3

Clearly Bartram had encountered a people who had perfectly adapted to their part of the world. Despite the colonies’ unsettled political situation and white encroachment, the Seminoles were prospering. Even without European trade goods, which had thoroughly penetrated the local culture in the form of flintlock muskets, iron hatchets, pots, and tools, glass beads, bright cloth, and cotton hunting shirts, there were more than enough natural resources to maintain their existence. The woods were thick with deer, bear, opossum, and rabbit, and cultivated fields of corn, beans, squash, and melon ringed the village. The Suwannee, broad and deep at Talahasochte, was an especially productive larder. Its muddy banks were populated by crawfish, turtles, and frogs sheltered by scuppernong, persimmon, laurel oak, and blueberry. The water immediately next to the banks, Bartram noted, was “turbid” and swarming with “amphibious insects,” providing an ideal nursery for small fry, which in turn became food for the larger fish. Midstream the water was startlingly clear and teeming with “finny inhabitants.” On one short expedition, Bartram delighted in hooking trout so large they actually pulled the canoe “over the floods before we got them in.” After catching several he was hailed by a canoe of Indians, “cheerful merry fellows,” who traded a mess of bream, “my favorite fish,” for some of the trout. Down on the Gulf, the Seminoles heavily fished the marshy river mouth’s tidal creeks and passes, smoking their catch and sometimes trading with Cuban fishermen. They also harvested mollusks and killed the occasional manatee, a bountiful source of fat.4

Like every other Indian tribe in the Americas, the Seminoles were descendants of a small East Asian founder group who migrated across the Bering Land Bridge some twenty thousand years earlier. By 12000 B.C.E. these peoples had advanced to the very ends of South America and were probably roaming the northern Gulf rim into Florida as well. By about 4000 B.C.E. they had filtered into Cuba, either from other Caribbean islands, Florida or both. All of these early Gulf inhabitants were Paleo-Indians, small bands of hunter-gatherers who moved constantly in search of the best game. Sea levels were much lower during the earliest phases of this period, and these Indians stalked megafauna such as mastodon, mammoth, bison, and sloths well out onto what is today submerged continental shelf. Those people closest to the ancient seashores learned to exploit the plenteous marine resources. Women and children foraged for mollusks and crustaceans while lithe adolescent boys probably indulged in a little hand fishing to test their skill. The men spear-fished and killed manatee and sea turtles, butchering the large carcasses with beautifully faceted stone knives.5

Over succeeding millennia the climate warmed, sea levels rose, and the megafauna disappeared or were hunted to extinction. In response the Indians adjusted their habits and improved their tools, entering what modern archaeologists refer to as the Archaic Period (7500–1000 B.C.E.). Groups became more settled and threw refuse like mussel shells, turtle bones, potsherds, and stone flakes onto small piles that eventually grew into larger middens, valuable sources of archaeological data. Increasingly skilled potters learned to temper their clay with Spanish moss and shredded palmetto leaves for additional strength before firing it. Women handwove natural materials into cloth, mats, and baskets. Hunters made smaller spear points and like their ancestors multiplied their throwing power with the atlatl, a small stick with a hooked base. When he wanted to throw his spear, a hunter simply fitted the base of his dart against the atlatl’s base, gripped it at the opposite end, and retaining his hold on the device hurled the spear. The atlatl acted as an extension of the thrower’s arm, essentially providing an extra elbow and significantly multiplying the throw’s force. No one knows exactly when, but it was also likely during this era that people first looked at the multitudinous waters of their world—rivers, streams, lakes, bays, bayous, and lagoons, as well as the blue-green Gulf itself—and decided to embark upon them.6

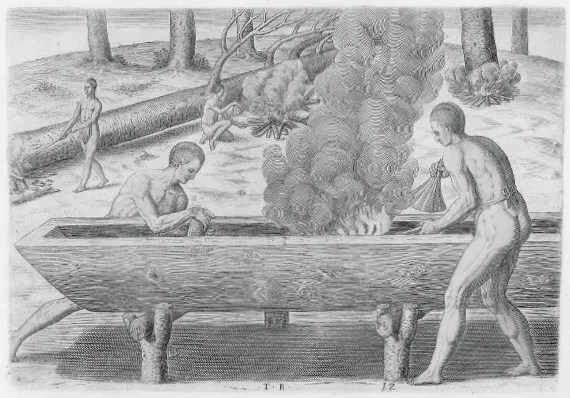

Simple dugout canoes were their means. The basics of making a good dugout probably changed little over the millennia, and an eyewitness description by the naturalist Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz in 1700s Louisiana may safely be considered the Indian standard until European trade goods changed everything. The builders’ first task was to select a likely tree—cedar, ceiba, or even mahogany in the Yucatán; cypress or poplar along the northern shore; or yellow pine in south Florida. Then they had to bring it down. Fire was the best method, since as du Pratz noted, stone axes “could not cut wood, but only bruise it.” After a small fire was set at the tree base the Indians let the flames do their work, perhaps chopping a bit here and there, until the great trunk fell with a crash. They then burned off the top, hacked off the limbs, and placed the trunk onto a large wooden frame. Hot coals were laid along the top of the log and, according to du Pratz, “when the wood is consumed it is scraped so that the insides may catch fire better and may be hollowed out more easily, and they continue thus until the fire has consumed all of the wood in the inside of the tree.” In order to control the burn and keep it from eating too deeply into the sides, ends, or bottom of the intended vessel, Indians carefully packed wet clay against the wood, thinning it or slathering on more as needed. The boat was finished off using scrapers and even shark skin as sandpaper. Canoe lengths varied, from short craft that could carry two or three people to large war canoes capable of holding dozens. “I have seen some 40 feet long by 3 broad,” du Pratz wrote. “They are about 3 inches thick which makes them very heavy.” Du Pratz claimed that the labor required to finish a good dugout was “infinite,” but steady effort could usually turn one out in a few weeks.7

How They Build Boats, Theodor de Bry, 1590. Indians fashion a dugout canoe using fire and hand tools. COURTESY LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

Dugout canoes proved highly serviceable on inland waterways and protected bays. Modern tourists and museumgoers are often surprised to learn this, since the vessels look so unstable. But the Indians were expert handlers, using paddles or poles to deftly propel and steer their craft toward another village or to check a fish trap. Even an unexpected capsize was no problem, according to one sixteenth-century Spaniard. If a canoe flipped, he explained, the Indians “take their vessel between them and turn it so as to have its mouth straight downward.” When it comes up full of water, “all simultaneously give it a shake, and when the water in falling is collected on one side, they immediately give it a shake in the opposite direction. After two such shakes, not a drop of water remains in the canoe, and the Indians reenter it.” It was all done in a twinkling. The numerous streams emptying into the Gulf, especially along the northern shore, were natural highways and far preferable to difficult overland routes through broken terrain, jungle, swamps, or thorny thickets. One careful student of the matter has calculated that water routes generally cut travel times to important points in half, and that four Indians paddling a canoe for fifty miles conserved twenty-five thousand calories over a comparable land journey.8

Unfortunately, dugouts possessed none of the qualities desired in a good sea boat. Their low ends lacked enough buoyancy to breast oncoming waves or manage a following sea, and the meager freeboard was dangerous in a heavy chop, though the gunwales could be augmented by plank strakes to reduce over wash and spray. Furthermore, their lack of tillers or keels meant poor stability and susceptibility to inefficient lateral movement while under way. Even so, as Bartram observed, American Indians were not afraid to venture into blue water when the occasion warranted. But it was not for the fainthearted. The Gulf’s frequent calms were an advantage, but the weather had to be watched closely, and one wonders how many Indian crews were lost to sudden squalls or rogue waves. There would be refinements to and variations among dugouts depending on the tribe and the era including different bow designs and, among the Calusa of southwest Florida, possible sail use and the development of catamarans, but the dugout was never to be a good ocean vessel.9

Rafts are easier to make than dugout canoes, as any schoolboy living near a creek knows, and the early Indians frequently resorted to them, especially when traveling overland and confronted by a stream to be crossed. Du Pratz wrote that the Louisiana Indians made rafts out of “bundles of canes bound side by side then crossed double (i.e., a second tier being placed at right angles crosswise).” This made a workable ferry that could be either broken up or left on the bank for future use. Down in Mexico, the enigmatic Olmecs (ca. 1200 to 400 B.C.E.) used big rafts to ferry giant sculpted basalt heads. Some of these heads weighed up to forty tons and were quarried and carved miles from their intended destinations. Gangs of Indian laborers rolled the heads across the ground on logs and maneuvered them onto rafts consisting of balsa trunks resting atop canoes. Once positioned on the raft, the fantastic assembly was towed by hundreds of Indians straining against long yucca lines.10

Over time some of the Gulf’s native inhabitants developed increasingly sophisticated cultures that at their apogee featured highly stratified city-states, monumental architecture, astronomical and mathematical knowledge, literacy, elaborate myth and ritual, organized warfare, extensive agricultural production, trade routes, and an ongoing dependence on and exploitation of the sea. There were far too many tribes over the centuries to adequately cover in a survey such as this, but by the eve of European contact several native groups were notable for their cultural and maritime achievements. They included the Maya in southern Mexico, the Indians around Mobile Bay, and the Calusa of Florida’s Mangrove Coast.

The Maya emerged out of the Mesoamerican Archaic era and by 500 B.C.E. had established themselves in Central America and Mexico. Scholars divide their civilization into preclassic, classic, and postclassic periods, with significant achievements occurring during each of these. When the Spanish first encountered the Maya during the late postclassic period, they were in decline but still formidable. Even at their peak they were never a unified people, settling rather into small city-states that shared a common culture and alternatively warred and traded with one another. Their greatest cities, such as Tikal and El Mirador (in Guatemala) and Uxmal and Chichén Itzá (in northern Yucatán) are now popular tourist destinations, famous for their awe-inspiring stepped pyramids as much as two hundred feet in height, paved plazas, palaces, temples, ball courts, and elaborate sculpture. Each city-state had a king and royal family, a warrior elite, noble priests who conducted frequent and bloody human sacrifices, and tens of thousands of commoners who labored in town and tilled the nearby fields.11

The Maya’s physical geography included highlands to the south and the Yucatán’s broad flat lowlands to the north where the bordering Gulf and Caribbean provided plentiful food, and meaning, to their society. The Spanish priest Diego de Landa wondered that the Maya had been able to survive on the stony Yucatán Peninsula at all, calling it the “country with the least earth that I have ever seen, since all of it is one living rock.” Yet the Maya carved out their cities amid the dense forests and improved their prospects by draining swamps, building up fields, constructing irrigation canals to deal with the long dry season, and maintaining household garden patches of maize, beans, squash, and peppers. In the surrounding country they practiced conservation techniques to preserve deer stocks. Along the Peninsula’s northern margin, just off the Gulf, stretched a large saline marsh that yielded what Landa called “the finest salt I have seen in my life.” During the rainy season clumps of the highly desirable mineral appeared on the surface so thickly that, according to Landa, it looked just like “sugar candy.” The natives regularly harvested this bounty, trading it far and wide. Lastly, impressive natural limestone cenotes, or sinkholes, dot the northern third of the Peninsula and served the Maya as sacred shrines and reliable freshwater wells.12

Water was important to the Maya for several reasons. They needed it to live, of course, but it also physically linked them together via streams and the sea, and metaphorically defined their spiritual horizons and bounded their underworld. The Mayan pantheon was crowded by dozens of deities, but among the most important were the founder gods Kukulkán (the feathered serpent known as Quetzalcoatl to the Aztecs) and Hurakan. Scholars surmise that Kukulkán was based on an actual warrior prince who arrived at Chichén Itzá around 1000 C.E. and was deified. His cult soon spread, and the Maya came to believe that when he left them he went east over the sea, promising to return. This myth was eventually to bear disastrous fruit for all the Mesoamerican peoples, but prior to that it gave daring and ambitious warriors a powerful motivation to journey offshore. Hurakan, by contrast, was a fearsome storm god who could summon howling winds and lashing rains to knock down trees and destroy villages. Hurakan had conjured the very earth from beneath the ocean, the Maya believed, and populated it with sluggish mud men, whom he subsequently destroyed with water. When Hurakan wasn’t visiting ruinous floods on people, the god Chaak was in charge of the rain, and the deeper cenotes were thought to be portals into his realm. If these gods wanted to travel through the watery underworld themselves, they depended on a pair of paddler gods and, what else but a dugout canoe.13

Frighteningly, the diverse Maya pantheon had to be continually placated by human sacrifice and bloodletting. Sacrifice usually involved battle captives or losing ballplayers. The victims were marched to the pyramid tops, held down upon stone altars, and their chests ripped open by longhaired priests wielding obsidian knives. Their hearts were displayed to throngs below and offered to the gods, their bodies unceremoniously thrown down the steps. During drough...