eBook - ePub

Imperialism A Study

John Atkinson Hobson

This is a test

Share book

- 418 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Imperialism A Study

John Atkinson Hobson

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Imperialism A Study an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Imperialism A Study by John Atkinson Hobson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Imperialism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE ECONOMICS OF IMPERIALISM

CHAPTER I

THE MEASURE OF IMPERIALISM

QUIBBLES about the modern meaning of the term Imperialism are best resolved by reference to concrete facts in the history of the last thirty years. During that period a number of European nations, Great Britain being first and foremost, have annexed or otherwise asserted political away over vast portions of Africa and Asia, and over numerous islands in the Pacific and elsewhere. The extent to which this policy of expansion has been carried on, and in particular the enormous size and the peculiar character of the British acquisitions, are not adequately realised even by those who pay some attention to Imperial politics.

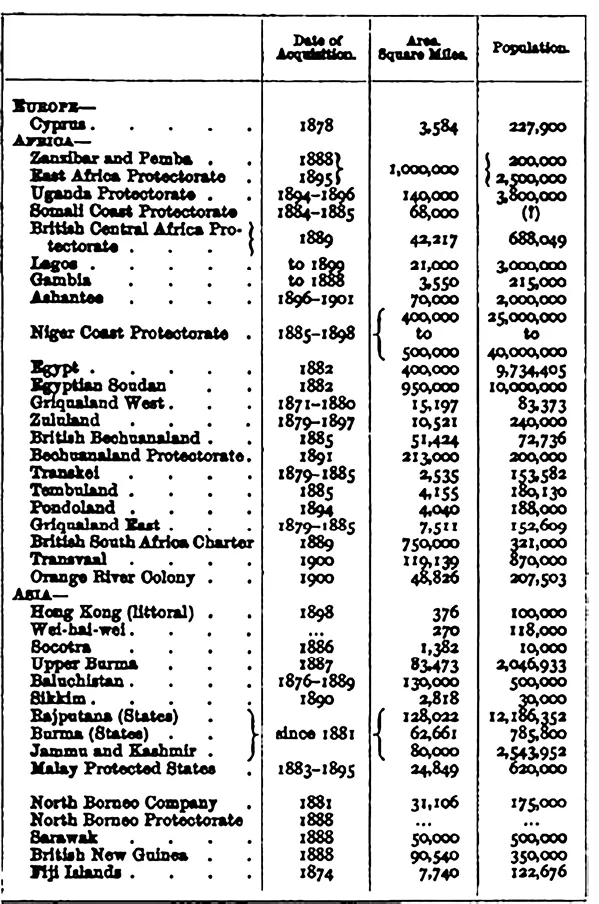

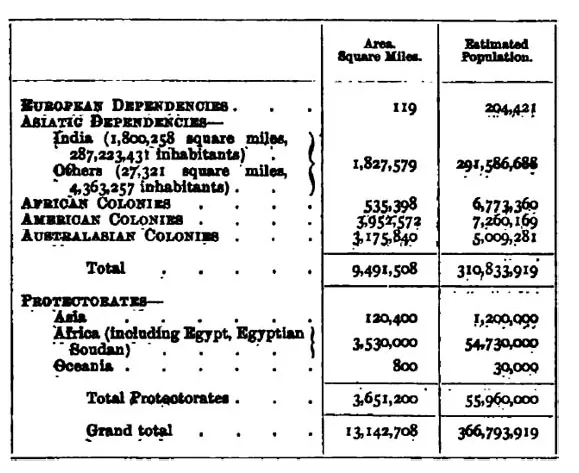

The following lists, giving the area and, where possible, the population of the new acquisitions, are designed to give definiteness to the term Imperialism. Though derived from official sources, they do not, however, profess strict accuracy. The sliding scale of political terminology along which no-man’s land, or hinterland, passes into some kind of definite protectorate is often applied so as to conceal the process; “rectification” of a fluid frontier is continually taking place; paper “partitions” of spheres of influence or protection in Africa and Asia are often obscure, and in some cases the area and the population are highly speculative.

In a few instances it is possible that portions of territory put down as acquired since 1870 may have been ear-marked by a European Power at some earlier date. But care is taken to include only such territories as have come within this period under the definite political control of the Power to which they are assigned. The figures in the case of Great Britain are so startling as to call for a little further interpretation. I have thought it right to add to the recognised list of colonies and protectorates the “veiled Protectorate” of Egypt, with its vast Soudanese claim, the entire territories assigned to Chartered Companies, and the native or feudatory States in India which acknowledge our paramountcy by the admission of a British Agent or other official endowed with real political control.

All these lands are rightly accredited to the British Empire, and if our past policy is still pursued, the intensive as distinct from the extensive Imperialism will draw them under an ever-tightening grasp.

In a few other instances, as, for example, in West Africa, countries are included in this list where some small dominion had obtained before 1870, but where the vast majority of the present area of the colony is of recent acquisition. Any older colonial possession thus included in Lagos or Gambia is, however, far more than counterbalanced by the increased area of the Gold Coast Colony, which is not included in this list, and which grew from 29,000 square miles in 1873 to 39,000 square miles in 1893.

The list is by no means complete. It takes no account of several large regions which have passed under the control of our Indian Government as native or feudatory States, but of which no statistics of area or population, even approximate, are available. Such are the Shan States, the Burma Frontier, and the Upper Burma Frontier, the districts of Chitral, Bajam, Swat, Waziristan, which came under our “sphere of influence” in 1893, and have been since taken under a closer protectorate. The increase of British India itself between 1871 and 1891 amounted to an area of 104,993 Square miles, with a population of 25,330,000, while no reliable measurement of the formation of new native States within that period and since is available. Many of the measurements here given are in round numbers, indicative of their uncertainty, but they are taken, wherever available, from official publications of the Colonial Office, corroborated or supplemented from the “Statesman’s Year-book.” They will by no means comprise the full tale of our expansion during the thirty years, for many enlargements made by the several colonies themselves are omitted.

But taken as they stand they make a formidable addition to the growth of an Empire whose nucleus is only 120,000 square miles, with 40,000,000 population.

For so small a nation to add to its domains in the course of a single generation an area of 4,754,000 square miles,1 with an estimated population of 88,000,000, is a historical fact of great significance.

Accepting Sir Robert Giffen’s estimate2 of the size of our Empire (including Egypt and the Soudan) at about 13,000,000 square miles, with a population of some 400 to 420 millions (of whom about 50,000,000 are of British race and speech), we find that one-third of this Empire, containing quite one-fourth of the total population of the Empire, has been acquired within the last generation. This is in tolerably close agreement with other independent estimates.3

The character of this Imperial expansion is clearly exhibited in the list of new territories.

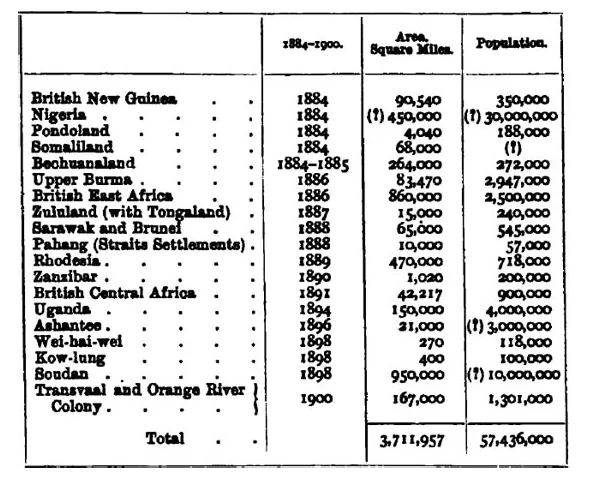

Though, for convenience, the year 1870 has been taken as indicative of the beginning of a conscious policy of Imperialism, it will be evident that the movement did not attain its full impetus until the middle of the eighties. The vast increase of territory, and the method of wholesale partition which assigned to us great tracts of African land, may be dated from about 1884. Within fifteen years some three and three-quarter millions of square miles have been added to the British Empire.4

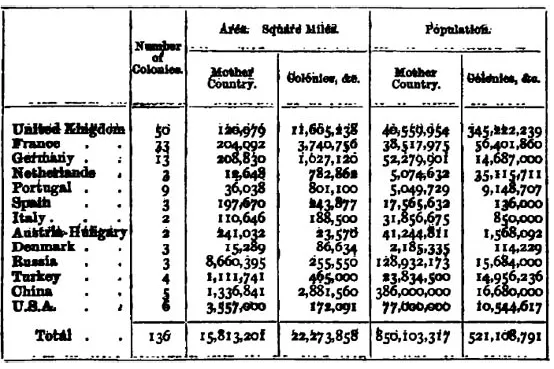

Nor does Great Britain stand alone in this enterprise. The leading characteristic of modern Imperialism, the competition of rival Empires, is the product of this same period. The close of the Franco-German war marks the beginning of a new colonial policy in France and Germany, destined to take effect in the next decade. It was not unnatural that the newly-founded German Empire, surrounded by powerful enemies and doubtful allies, and perceiving its more adventurous youth drawn into the United States and other foreign lands, should form the idea of a colonial empire. During the seventies a vigorous literature sprang up in advocacy of the policy5 which took shape a little later in the powerful hands of Bismarck. The earliest instance of official aid for the promotion of German commerce abroad occurred in 1880 in the Government aid granted to the “German Commercial and Plantation Association of the Southern Seas.” German connection with Samoa dates from the same year, but the definite advance of Germany upon its Imperialist career began in 1884, with a policy of African protectorates and annexations of Oceanic islands. During the next fifteen years she brought under her colonial sway about 1,000,000 square miles, with an estimated population of 14,000,000. Almost the whole of this territory is tropical, and the white population forms a total of a few thousands.

(Compiled from Morris’ “History of Colonisation,”

vol. ii. P. 87, and “Statesman’s Year-book,” 1900.)

Total area, British Empire, January 1884—

square miles, 8,059,179. Population, 248,000,000.

Similarly in France a great revival of the old colonial spirit took place in the early eighties, the most influential of the revivalists being the eminent economist, M. Paul Leroy-Beaulieu. The extension of empire in Senegal and Sahara in 1880 was followed next year by the annexation of Tunis, and France was soon actively engaged in the scramble for Africa in 1884, while at the same time she was fastening her rule on Tonking and Laos in Asia. Her acquisitions since 1880 (exclusive of the extension of New Caledonia and its dependencies) amount to an area of over three and a half million square miles, with a native population of some 37,000,000, almost the whole tropical or sub-tropical, inhabited by lower races and incapable of genuine French colonisation.

Italian aspirations took similar shape from 1880 onwards, though the disastrous experience of the Abyssinian expeditions has given a check to Italian Imperialism. Her possessions in East Africa are confined to the northern colony of Eritrea and the protectorate of Somaliland.

Of the other European States; two only, Portugal6 and Belgium, enter directly into the competition of the new Imperialism. The African arrangements of 1884–6 assigned to Portugal the large district of Angola on the Congo Coast, while a large Strip of East Africa passed definitely under her political control in 1891. The anomalous position of the great Congo Free State, eeded to the King of Belgium in 1883, and growing since then by vast accretions, must be regarded as involving Belgium in the competition for African empire.

Spain may be said to have definitely retired from imperial competition. The large and important possessions of Holland in the East and West Indies, though involving her in imperial politics to some degree, belong to older colonialism: she takes no part in the new imperial expansion.

Russia, the only active expansionist country of the North, stands alone in the character of her imperial growth; which differs from other Imperialism in that it has been principally Asiatie in its achievements and has proceeded by direct extension of imperial boundaries, partaking to a larger extent than in the other cases of a regular colonial policy of settlement for purposes of agriculture and industry. It is, however, evident that Russian expansion, though of a more normal and natural order than that which characterises the new Imperialism, comes definitely into contact and into competition with the claims and aspirations of the latter in Asia; and has been advancing rapidly during the period which is the object of our study.

The recent entrance of the powerful and progressive nation of the United States of America upon Imperialism by the annexation of Hawaii and the taking over of the relics of ancient Spanish empire not only adds a new formidable competitor for trade and territory, but changes and complicates the issues. As the focus of political attention and activity shifts more to the Pacific States, and the commercial aspirations of America are more and more set upon trade with the Pacific islands and the Asiatic coast, the same forces which are driving European States along the path of territorial expansion seem likely to act upon the United States, leading her to a virtual abandonment of the principle of American isolation which has hitherto dominated her policy.

The following comparative table of colonisation, compiled from the “Statesman’s Year-book” for 1900 by Mr. H. C. Morris,7 marks the present expansion of the political control of Western nations:—

The political nature of the new British Imperialism may be authoritatively ascertained by considering the governmental relations which the newly annexed territories hold with the Crown.

Officially,8 British “colonial possessions” fall into three classes—(I) “Crown colonies, in which the Crown has the entire control of legislation, while the administration is carried on by public officers under the control of the Home Government; (2)...