- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Plant gene silencing is a crucially important phenomenon in gene expression and epigenetics. This book describes the way small RNA is produced and acts to silence genes, its likely origins in defence against viruses, and also its potential to improve plants. Plant gene silencing can be used to improve industrial traits, make plants more nutritious or more valuable to consumers, to remove allergens, and to improve resistance to weeds and pathogens.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Plant Gene Silencing by Tamas Dalmay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biotechnology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Diversity of RNA Silencing Pathways in Plants

Institut Jean-Pierre Bourgin, INRA, AgroParisTech, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, Versailles, France

*Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

1.1 Introduction

RNA silencing is a manifestation of eukaryote defences against exogenous invading nucleic acids. Indeed, infection by pathogens, including fungi, bacteria, viruses or viroids, generally results in the production of pathogen-specific short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), the hallmark of RNA silencing (Hamilton and Baulcombe, 1999; Navarro et al., 2008). When loaded onto ARGONAUTE (AGO) proteins, these siRNAs guide the cleavage of the long RNAs naturally encoded by the invader (Vaucheret, 2008). However, despite the highly sequence-specific effect of siRNAs, pathogen-derived RNAs generally are not eliminated because most pathogens encode proteins that counteract the biogenesis or the action of siRNAs (Pumplin and Voinnet, 2013; Csorba et al., 2015).

RNA silencing is also used to control endogenous invading nucleic acids such as transposable elements (TE). In fact, TE silencing is mandatory to prevent uncontrolled expansion of these elements within the genome and avoiding subsequent deleterious effects, including gene disruption, gene activation or internal recombination. Unlike viruses, TEs generally do not encode proteins that have the capacity to block RNA silencing. Therefore, TEs generally are efficiently controlled by RNA silencing. Nevertheless, the protection of TE RNAs by TE proteins has been reported (Mari-Ordonez et al., 2013). Moreover, TE silencing can be erased under certain stress conditions (for example heat stress), leading to transient expression of TE RNAs and possible TE movement (Pecinka et al., 2010; Ito et al., 2011).

In contrast to pathogens and TEs, endogenous protein-coding genes generally are not a source for siRNA production and therefore are not subjected to RNA silencing. Indeed, only a handful of endogenous genes, in particular varieties, have been shown to produce siRNAs at levels that allow blocking transcription (transcriptional gene silencing or TGS) or degrading mRNAs (post-transcriptional gene silencing or PTGS), depending whether the siRNAs derive from the promoter or the transcribed region. Remarkably, these varieties exhibit genomic rearrangements, involving either duplication events or TEs inserted within or adjacent to the gene, whereas regular varieties that lack such rearrangements do not produce siRNAs and do not show silencing (Coen and Carpenter, 1988; Bender and Fink, 1995; Cubas et al., 1999; Clough et al., 2004; Tuteja et al., 2004; Della Vedova et al., 2005; Manning et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2009; Tuteja et al., 2009; Durand et al., 2012). It is assumed that genomic rearrangements resulting in the silencing of endogenous protein-coding genes are tolerated because they affect dispensable genes, and that cells undergoing genomic rearrangements that provoke the silencing of essential genes do not survive. This hypothesis implies that, during evolution, endogenous protein-coding genes are shaped to avoid producing siRNAs and undergoing silencing.

1.2 Transgene-based Genetic Screens to Unravel Silencing Pathways

The situation of endogenous protein-coding genes contrasts sharply to that of transgenes, which often undergo RNA silencing, although they are designed to structurally resemble and function like endogenous protein-coding genes. Note that RNA silencing was actually discovered as an unintended consequence of plant transformation (Matzke et al., 1989; Napoli et al., 1990; Smith et al., 1990; van der Krol et al., 1990). Indeed, it is now known that introduction of transgenes in the form of naked DNA, or by infection with disarmed bacteria such as Agrobacterium, always activates the production of siRNAs (Llave et al., 2002). Following stable integration in the genome, transgenes are either expressed or silenced. Nevertheless, silencing sometimes occurs after a period of normal expression that can last several generations. The reasons why certain transformants express a transgene whereas others undergo silencing by TGS or PTGS remain not well understood, and this raises important issues about the reliability of transgene expression. Importantly, when the transgene undergoing silencing carries sequences derived from an endogenous gene, transgene-derived siRNAs also affect the endogenous copy or copies, a phenomenon referred to as co-suppression (Napoli et al., 1990).

The fact that transgenes frequently undergo silencing whereas endogenous protein-coding genes do not, indicates that transgenes are often perceived as invaders that need to be silenced like pathogens or TEs. During the transient phase of extra-chromosomal expression, transgenes are generally present in high copy number, which may result in abnormally high levels of RNAs, thus mimicking what happens with invader RNAs during an infection, and activation of RNA silencing. Following integration in genomic areas allowing high levels of transcription, transgenes can still continue to produce high levels of RNAs, thus maintaining RNA silencing active against them. Supporting this hypothesis, transgenes that carry strongly expressed promoters are generally more prone to undergo silencing than transgenes that carry weakly expressed promoters. Stable integration of several transgene copies within the genome can also activate anti-transposons RNA silencing. Supporting this second hypothesis, transgenic plants exhibiting high transgene copy numbers are generally more prone to undergo silencing than plants carrying single copies.

Almost 20 years ago, the first forward genetic screens based on the reactivation of silenced transgenes identified the core components of the PTGS and TGS pathways. Enhancer screens were then set up, revealing cellular functions that antagonize silencing. More recently refined genetic screens, including sensitized screens and suppressor screens, have allowed identification of a variety of regulatory components. So far, 12 and 18 forward genetic screens dedicated to PTGS and TGS, respectively, have been published. The outcome of these screens is described in Table 1.1 and Table 1.2. Because transgenes only serve as excellent reporters of endogenous functions, we do not describe further how each transgene locus is silenced. In the next sections, we describe what transgene-based genetic screens have told us about natural silencing pathways.

Table 1.1. Mutants identified in PTGS genetic screens.

Table 1.2. Mutants identified in TGS genetic screens.

1.3 PTGS Pathways

1.3.1 Antiviral PTGS

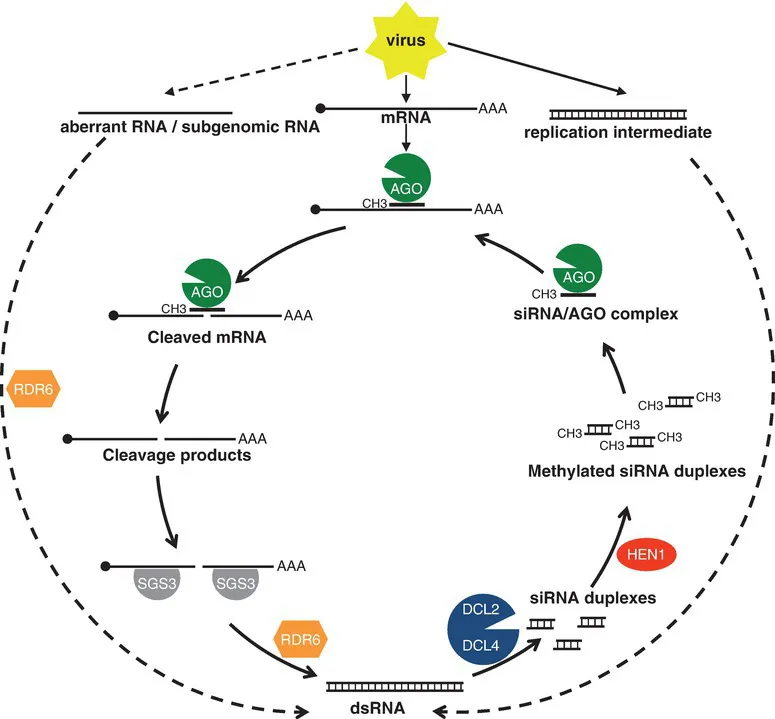

Antiviral PTGS starts by the processing of virus-derived dsRNA into 21- and 22-nt primary siRNAs by DICER-LIKE 4 (DCL4) and DCL2, respectively (Bouche et al., 2006; Deleris et al., 2006; Fusaro et al., 2006). Virus-derived dsRNA molecules represent either: (i) the natural form of dsRNA viruses; (ii) intermediate forms of the replication of ssRNA viruses; (iii) partially folded viral ssRNAs; or (iv) molecules resulting from the action of RNA-DEPENDENT-RNA-POLYMERASE (RDR) enzymes on aberrant or subgenomic viral ssRNA. Primary siRNAs are methylated at their 3´ end by the methyltransferase HUA ENHANCER 1 (HEN1) (Boutet et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005) before loading onto AGO proteins, mainly AGO1 and AGO2 but also AGO5 or AGO7 (Morel et al., 2002; Qu et al., 2008; Harvey et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011b; Brosseau and Moffett, 2015) to guide the cleavage of viral ssRNA through sequence homology. AGO-mediated cleavage generates RNA fragments that escape degradation due to the protective activity of SUPPRESSOR OF GENE SILENCING 3 (SGS3) (Mourrain et al., 2000; Yoshikawa et al., 2013). With the assistance of the putative RNA export protein SILENCING-DEFECTIVE (SDE5) (Hernandez-Pinzon et al., 2007), SGS3-protected cleavage products are transformed into dsRNA by RDR6 (Mourrain et al., 2000). These dsRNA are processed into siRNA duplexes by DCL4 to produce secondary siRNAs that reinforce AGO-mediated RNA cleavage, thus creating an amplification loop (Fig. 1.1). Such a process should eliminate viral RNA; however, most viruses have developed strategies to handle PTGS by expressing proteins called VSR (viral suppressors of RNA silencing), which block one or other of the steps of the PTGS pathway (Pumplin and Voinnet, 2013; Csorba et al., 2015).

Fig. 1.1. Model for antiviral PTGS. Dashed arrows indicate putative initiation routes. Plain arrows indicate the amplification step. See section 1.3.1 of the text for details on the mechanisms and for additional actors involved.

This antiviral PTGS model also explains how PTGS is activated against sense transgenes that are not supposed to produce dsRNAs. Accordingly, transgenes that produce aberrant RNAs in sufficient amounts to escape degradation by nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA quality control (RQC) pathways (see below) are transformed into dsRNA by RDR6. The nature of transgene aberrant RNAs has long remained a mystery until the recent identification of uncapped transgene RNAs resulting from the 3´ end processing of readthrough transcripts (Parent et al., 2015b). RDR6-derived transgene dsRNAs are processed into 21-nt and 22-nt primary by DCL4 and DCL2 (Parent et al., 2015a), and loaded onto AGO1, which cleaves complementary target RNAs (Morel et al., 2002; Baumberger and Baulcombe, 2005). Transgene RNA cleavage fragments are transformed into dsRNA through the action of SGS3, SDE5 and RDR6 (Mourrain et al., 2000; Jauvion et al., 2010) and processed into siRNA duplexes by DCL4 to produce secondary 21-nt siRNAs that reinforce the cleavage of transgene mRNA through AGO1. Additional factors contribute to the efficiency of transgene PTGS, for example the RNA helicase SDE3 that binds to AGO1 (Dalmay e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Diversity of RNA Silencing Pathways in Plants

- 2 Induction and Suppression of Silencing by Plant Viruses

- 3 Artificial Induction and Maintenance of Epigenetic Variations in Plants

- 4 Gene Silencing in Archaeplastida Algae

- 5 Gene Silencing in Fungi: A Diversity of Pathways and Functions

- 6 Artificial Small RNA-based Strategies for Effective and Specific Gene Silencing in Plants

- 7 Application of RNA Silencing in Improving Plant Traits for Industrial Use

- 8 Increasing Nutritional Value by RNA Silencing

- 9 RNA-based Control of Plant Diseases: A Case Study with Fusarium graminearum

- 10 Targeting Nematode Genes by RNA Silencing

- 11 Gene Silencing Provides Efficient Protection against Plant Viruses

- Index

- Back Cover