- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

History of the 508th Parachute Infantry

About this book

The 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment was an airborne infantry regiment of the United States Army, first formed in October 1942 during World War II at Camp Blanding, Florida by Lieutenant-Colonel Roy E. Lindquist, who would remain its commander throughout the war.

The 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment participated in Operation Overlord, jumping into Normandy at 2:15 a.m. on 6 June 1944, and was awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation for its gallantry and combat action during the first three days of fighting.

The Regiment also saw active service in Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands, jumping on 17 September 1944, and continued fighting the Germans in the longest-running battle on German soil ever fought by the U.S. Army, before crossing the border into Belgium.

They played a major part in the Battle of the Bulge in late December 1944, during which they screened the withdrawal of some 20,000 troops from St. Vith, defended their positions against the German Panzer divisions, and participated in the assault led by the 2nd Ranger Battalion to capture (successfully) Hill 400.

U.S. D-Day paratrooper William G. Lord II's History of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which was originally published in 1948, provides an extensive and fascinating chronicle for the period from October 20, 1942 to January 1, 1946, and will appeal to discerning World War II historians and scholars alike.

Richly illustrated throughout with photographs and maps, this volume also includes in its appendix a list of combat awards, unit citations, and battle casualties.

The 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment participated in Operation Overlord, jumping into Normandy at 2:15 a.m. on 6 June 1944, and was awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation for its gallantry and combat action during the first three days of fighting.

The Regiment also saw active service in Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands, jumping on 17 September 1944, and continued fighting the Germans in the longest-running battle on German soil ever fought by the U.S. Army, before crossing the border into Belgium.

They played a major part in the Battle of the Bulge in late December 1944, during which they screened the withdrawal of some 20,000 troops from St. Vith, defended their positions against the German Panzer divisions, and participated in the assault led by the 2nd Ranger Battalion to capture (successfully) Hill 400.

U.S. D-Day paratrooper William G. Lord II's History of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which was originally published in 1948, provides an extensive and fascinating chronicle for the period from October 20, 1942 to January 1, 1946, and will appeal to discerning World War II historians and scholars alike.

Richly illustrated throughout with photographs and maps, this volume also includes in its appendix a list of combat awards, unit citations, and battle casualties.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

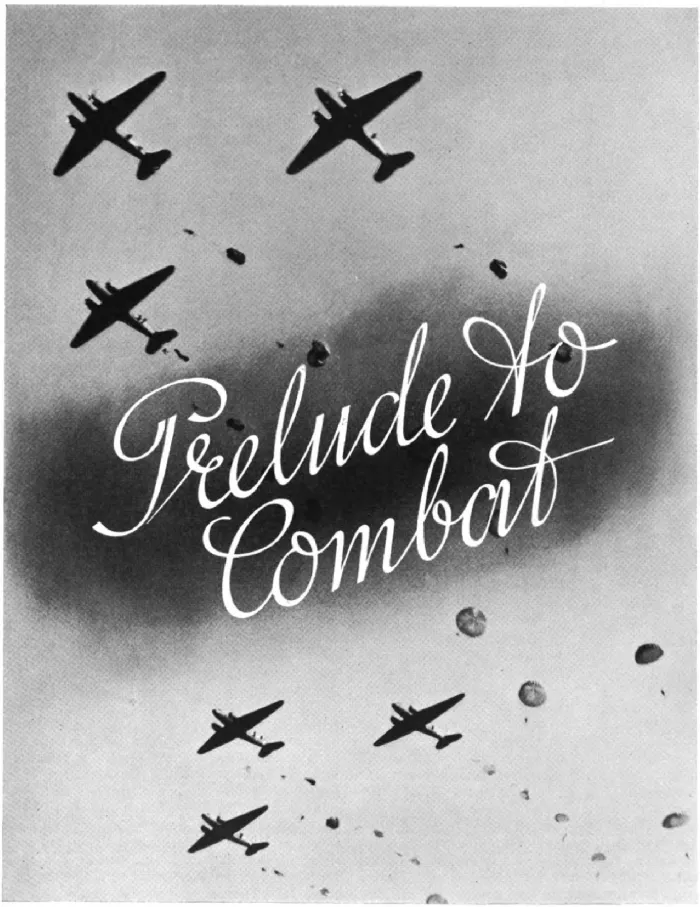

PART ONE: PRELUDE TO COMBAT

ON the 20th of October, 1942, the 508th Parachute Infantry was born at Camp Blanding, Florida, This date, however, in no way marked the beginning of the formation of a new regiment in the United States Army, for since early in September Major Roy E. Lindquist had been laying plans for the activation of the unit he was to command.

The cadre for the 508th came almost entirely from three sources; the 502nd Parachute Infantry, the Parachute School at Fort Benning, and the 26th Infantry Division. Every officer and man who became a part of the cadre was personally screened by Major Lindquist. Before they could be expected to tram recruits, these officers and men had to satisfy the major that they were thoroughly versed in matters military, and so special training was given the cadre at Fort Benning. Not all of the cadre had qualified at the Parachute School, but in each mind was imbedded the belief that the parachutist in the U.S. Army was the best soldier in the world, and it was around this belief that the morale of the new outfit was to be built.

On the 20th of October at Blanding troop trains began to arrive bringing the regimental commander, now a lieutenant colonel, and his first recruits—men who had been in the Army only a few weeks and who had volunteered for parachute duty. The average age of the new arrivals was low, under twenty. Most were in excellent physical and mental shape, and those that weren’t were immediately transferred. For six weeks the processing of the new men went on, and the Regiment was built up to full strength, battalion by battalion. By the middle of December the regimental strength was 2300 officers and men, but 4500 had to be processed before this number was accepted.

The first days in Camp Blanding were almost a repetition of what had gone on in the reception centers with the very noticeable difference of a tightening of discipline. There was the thorough physical exam, the drawing of equipment, and the innumerable shots with the huge hooked needle. In addition there was the comprehensive program of physical training, consisting of calisthentics, tumbling, rope-climbing, and running. Every time there was a spare moment, it became normal procedure to run a mile. Soon it was hard to convince the men that they weren’t training for a track meet.

As well as the physical sorting of candidates for the Regiment, a board of officers was set up in each battalion to determine the mental fitness of every man. Sometimes it became difficult for the new arrivals to realize that they were to form a regiment of rough-and-tumble parachutists. Major Louis G. Mendez, Jr., commanding the 3d Battalion, tested the mental alertness of his men by firing questions at them in rapid succession: “What is your name? Why? Is Mickey Mouse a boy or girl? Lift your left foot off the ground. Lift your right foot off the ground. Lift both feet off the ground.” By the time the interview was over, the recruit was not sure exactly what he had gotten himself into.

After these first active days, life in the Regiment settled down to a steady grind of hard work. From six in the morning till six in the evening the men of the 508th trained. A typical work day started at 0730 after breakfast and general clean-up of barracks. A half-hour run was followed by calisthenics at which Lieutenant Fleming presided. Addressing his attention to a battalion at a time, Lieutenant Fleming got more work out of the men in half an hour than most had believed it possible to accomplish in a week. His bellowing voice made a public-address system unnecessary and gave each man the idea that he was being watched personally by the huge man on the platform, as physical maneuvers unknown even to a yogi were attempted. The rest of the morning was spent doing close-order drill, the manual of arms, and listening to lectures on military subjects.

After a noon meal which often left something to be desired by these men with huge appetites, the work started again. Weapons drill or a speed march was followed by an hour of physical hardening. There were those who believed that the regimental commander was offering large prizes to the officers who could think of the most diabolical ways to spend this last period. One of the most frequently used exercises was a game where half the men attempted to climb the limbless pines that covered the camp while the other half was engrossed in the work of hauling them down. The whole was accompanied by a great twisting of arms, legs, and necks.

Within a few weeks men were qualifying on the range with weapons they had not even seen till they came to Blanding. The physical conditioning of the Regiment was rapidly approaching a peak. The morale of the Regiment, despite the lack of passes and the many restrictions, was excellent. After a gruelling day in the field, the men would sometimes answer chow call by running and tumbling out of their huts.

A few weeks previous to Christmas passes were issued for Christmas shopping in nearby Jacksonville. A few scientific experiments designed to test the extent of the toughness recently attained in camp made this the last day of passes till the Regiment was ready to move to jump school some months later.

Proficiency in military skills was increased by creating company competition throughout the Regiment. Streamers were placed on the guidon of the company that had proven itself best in qualifying with basic weapons, in doing close-order drill, and in achieving physical prowess. A regimental contest was opened for the best suggestions for a regimental patch to be worn on the field jacket and the best war-cry for the regiment. Sergeant Andrew J. Sklivis won the contest with a drawing of a parachuting red devil carrying a grenade and a tommy-gun. The adopted battle-cry was “Diablo!”

By the end of January interest in moving to jump school was rabid. The reason most men tried so hard to complete their basic training in the best possible manner was to qualify for a chance to go to jump school. Unsatisfactory results in any phase of the first month’s work at Blanding resulted in the loss of this opportunity for some individuals. Soon it got so every class held was greeted by the instructor with, “How many days?” The answer shouted in unison by all present was the number of days remaining before the Regiment would begin the move to Fort Benning.

Parades were held about once a week to insure that the Regiment was smart-looking as well as a highly trained organization. It did not take long for the men to become proud of their Regiment, the only airborne unit on the post. Even punitive measures were constructive. A lapse in memory, a blunder, or any inefficiency was rewarded by the assignment of a number of push-ups to the offender.

When the move to the Parachute School was initiated by the 1st Battalion on the 3rd of February, 1943, the physical and mental alertness of the men could properly be called superior. Many men have remarked since that they had never seen a unit in such good shape as the Regiment was when it left Blanding. Twenty-three hundred civilians had been transferred into good soldiers in a few short months.

II

On detraining at Fort Benning, Georgia, and looking around the first things to strike the newcomer’s eyes are the four 250-foot jump towers on the training field of the Parachute School. On viewing these steel mammoths the men of the 508th grew tense with anticipation.

Back in Camp Blanding one of the officers who had already qualified at the Parachute School had remarked to his men that going through the school was much like going to an amusement park, except that all attractions were free. When the 1st Battalion was taken on a tour of the school a few days before their class began, these words seemed to bounce back in their face. Jump school to them seemed more like an assembly of medieval tortures.

Because of the intensive physical training program which was inaugurated in the Regiment at Camp Blanding, the first week of the course at the Parachute School, known as “A” Stage, was omitted by the 508th. Normally this week consisted of eight hours a day of tumbling, judo, calisthenics, and running. Designed originally to build up the men for the following three weeks of work, this hell week seemed rather to have a deteriorating effect on most of those who survived it.

Work for the Regiment therefore, began in B” Stage. The outfit was divided into three classes of battalion strength which followed each other at one-week intervals. The first week of work for each class was divided into four hours a day learning to pack parachutes, and four hours a day on the low towers. Several devices, not really diabolical when compared to what was held in store for the following weeks, were evidenced at this time.

First, there was the suspended harness. This was a parachute harness hung from a ring several feet above the ground with which the student was supposed to learn to maneuver his chute, and from which he was taught to execute several kinds of quick escapes for water and tree landings. For the beginner at least one strap usually stuck, making the quick release a faulty and sometimes embarrassing operation.

When this had been mastered, or when the allotted time had been devoted to it, the class moved to the landing trainer. Here on a suspended harness attached to an inclined ramp the student learned to land forwards and backwards, and to make a quick body turn while landing. If everything was not done properly here, a good bit of time was spent double timing around the training field wearing the heavy harness on special invitation from the instructors.

The final piece of special equipment used here was the mock tower. This was a wooden imitation of the door of a C-47 on top of a platform thirty-five feet high. The tower was placed between two poles between which was suspended a cable. To the cable on a trolley was fastened a parachute harness. At a signal from the instructor the student leaped from the door, fell free for eighteen feet, and then was snapped out for a ride down the wire to a sawdust landing pit. Here too proper form and composure were necessary to prevent several trips around the field. By Saturday afternoon everyone was ready for the twenty-four-hour rest which preceded the next phase.

The second week of training at the Parachute School for the men of the 508th was again a combination of half-days in the packing sheds and half days on the training field. This time all the work Centered around the 250-foot towers. The first ride was in the control tower, wher...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- MAPS

- LEGEND

- FOREWORD

- PART ONE: PRELUDE TO COMBAT

- PART TWO: NORMANDY

- PART THREE: HOLLAND

- PART FOUR: THE ARDENNES

- PART FIVE: OCCUPATION

- BATTLE CREDITS

- HONOR ROLL

- APPENDIX I-HIGHLIGHTS OF THE REGIMENTAL HISTORY

- APPENDIX II-MEN KILLED IN TRAINING ACCIDENTS

- APPENDIX III-BATTLE CASUALTIES

- APPENDIX IV-COMBAT AWARDS

- APPENDIX V-COMBAT AWARDS

- FOREIGN DECORATIONS

- APPENDIX VI - BATTLEFIELD COMMISSIONED OFFICERS

- APPENDIX VII-UNIT CITATIONS

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access History of the 508th Parachute Infantry by William G. Lord II in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.