![]()

Turkish troops muster on the Plain of Esdraelon in preparation for the attack on the Suez Canal. All Ottoman Army infantry divisions were permitted a military band. Under combat conditions the bandsmen performed duties as litter bearers and orderlies.

CHAPTER 1

Suez and the Caucasus

The assault on the town of Sarikamis, deep in the Caucasus Mountains, was the first major Ottoman offensive of the war, and sought to surround and annihilate the Russian forces present in the area. A further offensive aimed at severing the Suez Canal was launched, which sought to seriously damage the British Empire's commercial lifeline to its Eastern colonies. Both of these operations would end in failure.

As the Ottoman Empire tumbled towards war in autumn 1914, there were bitter disputes in Constantinople between Bronsart von Schellendorf and his Ottoman counterpart Hafiz Hakki Bey over the strategic direction of the coming conflict. The Ottomans had never foreseen a multi-front war against a combination of Great Powers and, especially, against their long-time friend Great Britain. Consequently, the concentration plan, which had been written the previous April for a war against Bulgaria, stripped away forces from Palestine and Mesopotamia and left the Caucasus devoid of reinforcements as well. In fact, the military deployment of the empire's armies did not align at all with the diplomatic situation as it developed. This situation vexed both men, who were aggressive professionals and, as both were trained general staff officers, recognized that wars are won by offensive action. Hafiz Hakki pushed for offensives in Caucasia, Palestine and even Persia while the Germans advocated an amphibious attack on the Russian Black Sea coastline.

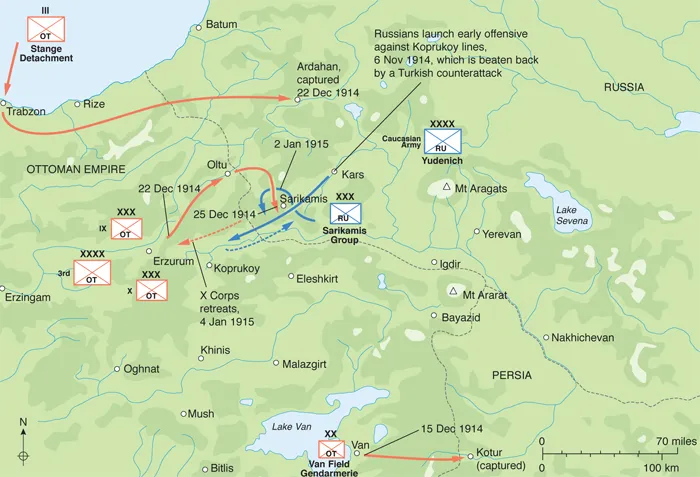

The Caucasus, November 1914–January 1915, including the Battle of Sarikamis. The Sarikamis encirclement was designed to create the conditions for an Ottoman version of Tannenberg and sought to annihilate the Russian Army.

In October, plans crystallized around offensives in the Caucasus and Palestine, and formal orders were sent to the respective armies. Liman von Sanders was offered command of the Ottoman Third Army, headquartered in the Anatolian city of Erzurum, but wisely declined. Although the Third Army and the Fourth Army in Palestine remained in the hands of Ottoman commanders, they had German chiefs of staff, Colonel Guse and Colonel von Frankenberg respectively, to coordinate and assist in planning. Although short of equipment, both armies were at full strength in manpower, much of which had combat experience in the recent Balkan Wars.

THE SARIKAMIS CAMPAIGN

The first major Ottoman offensive of the war was aimed at the town of Sarikamis, deep in the Caucasus Mountains, and which in December 1914 was blanketed with snow and gripped by sub-zero temperatures. It was the brainchild of Enver Pasha, and contrary to the version of events in most histories, was not a massive effort designed to recover lands inhabited by fellow Turkish peoples. Moreover, to this day Enver's plan is almost universally seen as recklessly ill conceived and doomed from the start. On the contrary, it was, in fact, carefully crafted and modelled on the German victory in September over the Russians at Tannenberg (in East Prussia); German operational reports from the latter indicated that when Russian units were surrounded, command and control collapsed and surrender soon followed. Enver envisioned a single envelopment of the over-extended Russian Army along the Ottoman northeast frontier, and thought that cutting their lines of communications at Sarikamis would force a collapse and surrender.

Turkish troops muster in 1914. This is the famous ‘Constantinople Fire Brigade’, which performed ceremonial guard duties as well serving as the city's fire fighters. They are easily distinguished by their helmets.

The actual planning guidance for offensive operations was sent from the general staff to the Ottoman Third Army in early September, when it became apparent that war against the Entente Powers was more likely than war against Bulgaria and Greece. There were two schools of thought within the staff concerning how this should be done: the first, from Colonel Bronsart von Schellendorf, envisioned a limited-scope offensive with the forces at hand, while the second, from Colonel Hafiz Hakki Bey, foresaw a massive reinforcement of the Third Army, which would enable a large-scale offensive complete with an amphibious landing north of Batum on the Black Sea. For his part, General Liman von Sanders thought neither idea was sound, and advanced the idea that the Turks should maintain a defensive strategic posture. As autumn set in, the Tannenberg reports began to arrive and Enver sent Bronsart von Schellendorf and Hafiz Hakki Bey to Berlin in late October 1914 for strategic consultations. When they returned (after the outbreak of hostilities), planning for a Caucasian offensive resumed in earnest as all opposition to an offensive strategic posture was extinguished.

Ottoman Encirclement Operations

The Ottoman Army embraced the ‘German way of war’ as a result of the establishment of the German general staff system and German war academy curriculum. Part of this German legacy included campaign planning for battles of encirclement and annihilation. The German curriculum glorified Hannibal's battle at Cannae as the ultimate expression of the operational art, and the Schlieffen Plan would come to exemplify this concept. Over a period of several decades Ottoman commanders became wedded to this doctrine. In the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, Ottoman commanders consistently tried to encircle their enemies, notably at the battles of Kirkkilise, Kumanova, Bitola and Sarkoy. This doctrinal pattern of planning for encirclement operations continued into World War I, notably at Sarikamis, Kut al-Amara, the Caucasus in 1916 and First Gaza. Ottoman commanders failed in these ambitious attempts to execute the ne plus ultra of the military art. In 1922, however, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk would destroy the Greek Army in a dramatic battle of encirclement and annihilation known as the Great Offensive.

Russian troops in the trenches at Sarikamis. One of the lessons learned by the Russian Army in the Russo-Japanese War was to dig trenches quickly. A group of staff officers can be seen observing from the centre of the trench line.

On 8 November 1914, the Ottoman Navy cruiser Mecidiye brought Hafiz Hakki Bey to Trabzon on the Black Sea coast. His mission was to energize the offensive spirit of the Third Army, and he went directly to the headquarters at Erzurum. There Hafiz Hakki Bey delivered explicit guidance to the chief of staff, German Colonel Guse, to prepare an operational offensive against the Russians. Tannenberg was used as a model of how this might be accomplished, and Hafiz Hakki Bey hoped to use the oncoming winter weather for additional leverage against the Russians. He encountered immediate resistance from the commanders of the Third Army and the IX Corps, who opposed the ambitious plan. Enver summarily relieved the latter, and sent a message to the army by placing Hafiz Hakki Bey in command of the corps.

Planning now proceeded at an accelerated rate, and the Turks secretly massed six of their nine available divisions (which were organized into the IX and X corps) into a powerful attack force along the left flank of the Koprukoy lines. The attack force was to march northeast through Oltu and then pivot sharply to the southeast toward Sarikamis, which lay on the only paved road leading from the Russian supply base at Kars to the Russian frontline troops facing Koprukoy. Possession of the town of Sarikamis effectively cut off the Russians from their rear, isolating them in winter weather; if the Tannenberg paradigm held true, this would cause confusion and a collapse in morale.

The general staff was unable to send large reinforcements for the Third Army offensive due to time constraints and the distances involved, but it was able to send the 8th Infantry Regiment by sea to Trabzon as a limited reinforcement and to conduct a diversionary operation. This operation would shield the northern flank of the Third Army in the area south of Batum by advancing on the city of Ardahan, acting as a sort of matador's cloak to distract the Russians. To the south of the operational area, the Third Army thinned its lines to allow the concentration of effort, leaving mostly cavalry and gendarmes to watch the long southern front.

The Russian Caucasian Army had five infantry divisions, two Cossack divisions, and a handful of infantry brigades and cavalry regiments. Altogether in October 1914, it comprised about 100,000 infantry, 15,000 cavalry and 256 guns. The nominal commander was the regional viceroy, but the real work of planning and organizing the army lay in the hands of the chief of staff, General Yudenich. The Ottoman Third Army was slightly smaller with about 90,000 infantry and 250 guns. The Ottoman cavalry was organized into a regular cavalry division and four reserve cavalry divisions of irregulars, formerly known as the Hamidiye cavalry, whose value in combat was debatable. The Turks fielded 4000 regular cavalry and possibly as many as 10,000 tribal warriors. The Russians broke their army down into tactical groups, the largest of which, the Sarikamis Group, stood at the Koprukoy lines and was composed of about 65,000 infantry and 172 guns. For the attack the Turks massed 49,000 men in their enveloping wing and left 27,000 men, including their cavalry (which was of limited value in the rugged mountains northeast of Erzurum), on the line. This deployment gave the Turks a small numerical margin of superiority over the troops of the Sarikamis Group.

The attack began before dawn on 22 December in good weather. Together with his assistant chief of staff Bronsart von Schellendorf, Enver Pasha had made the long journey to Erzurum and was on hand to watch the troops cross the frontier. The infantry of X Corps conducted a remarkable foot march advancing 75km (46 miles) through the mountains at Oltu to reach Sarikamis on 25 December. However, as they progressed the weather turned colder. The adjacent IX Corps also came up, so that the Third Army had two corps in position to attack Sarikamis. But as they approached the city the Turks began to encounter resistance centred on the old town. Unlike the events of August in the dark forests of East Prussia, the Russians in Sarikamis fought hard for the town. Moreover, their command and control apparatus remained intact and they were able to take several regiments off the Koprukoy line and send them to reinforce the Sarikamis garrison. In spite of this, the Turks took most of the old town. Reacting to this, on 28 December the Ottoman X Corps seized blocking positions to the north along the Kars–Sarikamis road, aiming to further weaken Russian resolve. Enver now expected a rapid Russian collapse, but instead the aggressive General Yudenich kept his head and coolly orchestrated a counterattack using forces pulled off the line and fresh forces from Kars. Yudenich's effective actions now gave the Russians numerical superiority in the immediate vicinity of Sarikamis. To make matters worse, the weather turned against the outnumbered Turks, with temperatures dropping to minus 26 degrees centigrade; the Turks were unprepared and lacked winter kit, having expected a quick victory. The tempo of fighting slowed and the Russians used this time to plan an encirclement of their own.

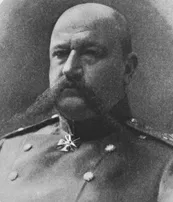

Nikolai Yudenich (1862–1933)

Yudenich was, arguably, the most successful Russian commander of World War I. Born in 1862, Yudenich entered the Imperial Russian Army in 1879, graduating from the General Staff Academy eight years later, after which he served on the general staff until 1902. He served in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 as a regimental commander and rose rapidly to general officer rank. Yudenich was appointed chief of staff of Russian forces in the Caucasian area in 1913 (having served as deputy chief of staff from 1907). He was instrumental in inflicting a series of defeats on the Turks, including that at Sarikamis in December 1914. In the following year he turned back Ottoman offensives, and captured Erzurum in February 1916 and Erzincan in July. In March 1917 Yudenich was forced to discontinue active operations in the Caucasus because of the ongoing revolution. The Provisional Government forcibly retired him and Yudenich fled to Finland during the October Revolution. He became a commander in the White armies and marched on Petrograd in the autumn of 1919, but was forced back into Estonia where the armies were disbanded. Fleeing for the second time, Yudenich went into exile in France, and died there in 1933.

Turkish riflemen en route to war. The Ottoman Empire had very few railroads. Those that existed were built by foreign entrepreneurs and seldom ran to the combat fronts. Ottoman soldiers usually deployed to their areas on foot.

‘There was one road out of the Turnagel Woods that night and only the X Corps returned – the IX Corps did not return.’

Colonel Hafiz Hakki, Ottoman General Staff, 1915

On 2 January 1915, Yudenich unleashed a powerful counter-offensive that swiftly re-enveloped the Ottoman left wing around Sarikamis. Enver reacted by placing both Ottoman corps under a single commander – ironically, the general staff's strategic planner Hafiz Hakki Bey, who had argued for the Caucasian offensive earlier in the autumn. The battered Turks tried to form a perimeter, but the Russians turned it into a noose. By 4 January 1915, Hafiz Hakki Bey was forced to choose between losing his entire force or leaving a rearguard to die while the others escaped. In the end, he left IX Corps in the Turnagel Woods to the northwest of Sarikamis in order to buy time for X Corps to retreat. IX Corps’ three infantry divisions were destroyed and its commander Ali Insan Pasha was captured with his staff. The Turkish collapse and the subsequent rout lost them an entire army corps – a third of Ottoman Third Army's combat strength.

The Sarikamis campaign ranks as one of the greatest military disasters of the twentieth century. It was neither badly planned nor badly conceived, rather it came up against unexpected and brilliantly effective the Russian command and control in the form of General Yudenich. A humiliated Enver, who had come to the front to glory in his victory, crept back to Constantinople in early January 1915. Western estimates of 90,000 Turks killed are exaggerated, with the actual losses consisting of some 30,000 dead and 7000 taken prisoner. In scenes reminiscent of Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, many of the casualties froze to death or suffered serious frostbite. The shattered Ottoman Third Army returned to its defensive positions to begin rebuilding itself.

At the same time as the Sarikamis campaign, Ottoman military activity took place to the north and southeast. To occupy the Russians and divert their attention and reserves from the Sarikamis region, the Ottoman general staff sent an infantry regiment and artillery by ship to the Black Sea port of Trabzon. Command of the regiment (and some frontier forces) was given to German Major Stange, a Prussian artilleryman who had been assigned to the fortress at Erzurum; the entire force was named the Stange Detachment. Stange's mission was to advance and tie down the Russian Army near Batum. Instea...