eBook - ePub

The New Testament in Antiquity, 2nd Edition

A Survey of the New Testament within Its Cultural Contexts

Gary M. Burge,Gene L. Green

This is a test

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The New Testament in Antiquity, 2nd Edition

A Survey of the New Testament within Its Cultural Contexts

Gary M. Burge,Gene L. Green

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This completely revised and updated second edition of The New Testament in Antiquity skillfully develops how Jewish, Hellenistic, and Roman cultures formed the essential environment in which the New Testament authors wrote their books and letters. Understanding of the land, history, and culture of the ancient world brings remarkable new insights into how we read the New Testament itself.

Throughout the book, numerous features provide windows into the first-century world. Nearly 500 full color photos, charts, maps, and drawings have been carefully selected. Additional features include sidebars that integrate the book's material with issues of interpretation, discussion questions, and bibliographies.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The New Testament in Antiquity, 2nd Edition an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The New Testament in Antiquity, 2nd Edition by Gary M. Burge,Gene L. Green in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

STUDYING THE

NEW TESTAMENT

A rolling stone tomb complex from the first century, Nazareth

Alamy Stock Photo

Alamy Stock Photo

PERSPECTIVE

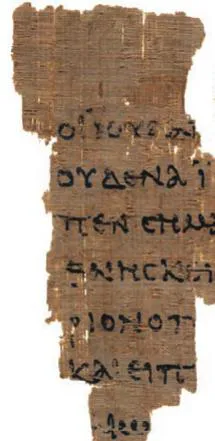

The New Testament consists of twenty-seven individual “books” written in Greek almost two thousand years ago, and some or all of the New Testament has been translated into 1,168 languages, a characteristic of no other book. Today about 2,500 new translations are underway.1 But it is not mere curiosity that inspires this study. It is the story contained in these books, a story about a Jewish Messiah and his followers that has led millions in every era to join the ranks of his disciples.

The New Testament is first and foremost about Jesus of Nazareth, a man called “Messiah” by his followers, who was killed in Jerusalem and who rose from the grave. His followers were transformed by what they saw and experienced, and they carried the gospel of Jesus to the entire Mediterranean world. The New Testament contains four gospels outlining Jesus’s life, a brief history of the early church, and a collection of letters from many of early Christianity’s most prominent leaders. They were penned during the fifty years or so following Jesus’s death and resurrection.

© The University of Manchester

Today many Christians know the basic elements of this story and enjoy an intimate, deeply personal love for many passages of the New Testament. But few understand the breadth of this story, much less how to interpret each book. Many of us gravitate to familiar texts but lack confidence interpreting more difficult sections. Some know the major characters, such as Jesus, Peter, and Paul, but are vague about the details of their lives or the more complex elements in their teachings.

The aims of this book are simple: to assist students to become alert, capable readers of the New Testament—to guide them through its many books, giving not only essential background information but also a digest of the New Testament’s most important teachings.

METHODOLOGICAL PRESUPPOSITIONS

All authors come to the task of writing with presuppositions. For instance, historical optimism—or skepticism—will unwittingly surface in every study of the New Testament. The same is true of this book. Its goals are the same as many other surveys of the New Testament, but some crucial differences will stand out in our approach to reading the New Testament.

Scripture and Study

As Christians we are eager to affirm our commitment that the New Testament is Scripture. These words of the Bible are not like other words; God has employed them—indeed, he still employs them—through the work of his Spirit in his church to reveal himself to the world. Therefore, we do not hold merely a historical or antiquarian interest in the New Testament. Rather, God is at work in and through these chapters to bring life and transformation to all who seek him there. Thus, it is appropriate for us to refer to the New Testament (as well as the entire Bible) as Scripture, or the divinely inspired Word of God.

This high affirmation of the Bible does not mean that readers in the twenty-first century are capable of understanding the New Testament as if by magic. The message of the Bible may be timeless, but the form of that message is not. To accomplish his self-revelation in history, God necessarily had to embed that revelation in the historical and cultural context of its original readers. When Jesus told a parable, he framed it in ways that made sense to first-century farmers and fishermen. When Paul wrote a letter, he used not only his own personal cultural preferences, but he wrote to be understood, using words and ideas meaningful to a first-century audience. Today we may understand a great deal of that message, but probing its depths requires effort. In many ways, we are foreigners to this story, outsiders looking in and struggling to comprehend it fully. Which means that we will need to become historians and archaeologists as we read these ancient manuscripts.

A Reader’s Bias

Meaning can be missed not only by our ignorance of ideas and images presupposed by the New Testament’s original audience but also by the cultural framework we ourselves bring to the task of study. Without realizing it, we bring the cultural values and the historical framework of our own world to the text of the New Testament. This is understandable. We only make sense of something we read when the concepts we encounter register with something in our own experience. When we read about the “church” of Corinth, our own images of “church” leap quickly to mind. When Jesus refers to a “sower,” our Western notions of farming and seed distribution fill in the picture. Readers bring their own understanding—sometimes called preunderstanding—to any text they encounter.

How do we cope with this? First, we work hard to understand our own context. That is, as interpreters of the New Testament we must become increasingly suspicious of our own preferences and ourselves. For example, if we come from a highly individualistic culture (so common in the West) in which the church emphasizes private salvation, we may have difficulty understanding the biblical notion of corporate sin. Or we may be unprepared to see how Jesus’s proclamation of “the kingdom of God” had social and economic implications. If we come from a society where religion and politics are strictly separated, it may be impossible to see how Jesus’s kingdom bore down on the political structures of his day.

Second, we must embrace the cultural context of the biblical world. If we do not share some of the reflexes of Paul’s first readers, if we cannot appreciate the difficulties of gentiles and Jews living side by side in first-century churches, it will be impossible to understand much of the New Testament. This means that the ancient context has precedence because we are interpreting ancient texts. What may seem perfectly obvious to us may not have been obvious to an original ancient reader. This matter of contextual precedence is often behind many disputed passages of the New Testament. When Paul writes, “Does not the very nature of things teach you that if a man has long hair, it is a disgrace to him?” (1 Cor. 11:14) we have to pause and think carefully about Paul’s appeal to what is “natural.” Natural to whom? And what is “long hair,” and why did Paul think it was important? Questions from culture and context pile up quickly around a little text like this.

Context, Context, Context

Words have a certain indeterminacy of meaning. That is, they gain meaning only when they are set firmly in a context. If a modern politician is referred to as “green,” it could mean a variety of things. She could be “new” to the field, deeply jealous, an environmentalist, or belong to a party that wears green uniforms. Perhaps she is Irish. For that matter, one of our authors is named “Green.” Perhaps that is the politician’s surname! We have no idea. In other words, “green” has little meaning unless it is tied to a context. The meaning of the word itself is not “determined” without a context. It must fit its range of meanings, or what is called its semantic range. Green cannot mean some things (green cannot mean “red”), but it can mean a lot of other things within limits.

For us to understand the New Testament effectively, therefore, we must rebuild the context of its words as carefully as possible. When John the Baptist introduces Jesus as the “Lamb of God” (John 1:36), does he mean that Jesus is meek? Or helpless? Or does it refer to lambs that are sacrificed at Jerusalem’s temple? If this refers to sacrifice, what sacrificial ceremony does John have in mind? The daily sacrifices of temple worship? Or the great annual Passover sacrifices each spring? Knowing the context is the key. But without the context, the phrase “Lamb of God” has little usefulness or meaning. The job of interpretation thus requires humility of the first order because we are admitting that we are reading this story as foreigners and outsiders, not as readers who share its original context.

The title of this book is deliberate: The New Testament in Antiquity. Our primary responsibility is to gain the meaning of our Scriptures by understanding not only our own interpretative contexts but also the original context of the New Testament. The context of antiquity should control how we understand the New Testament today.

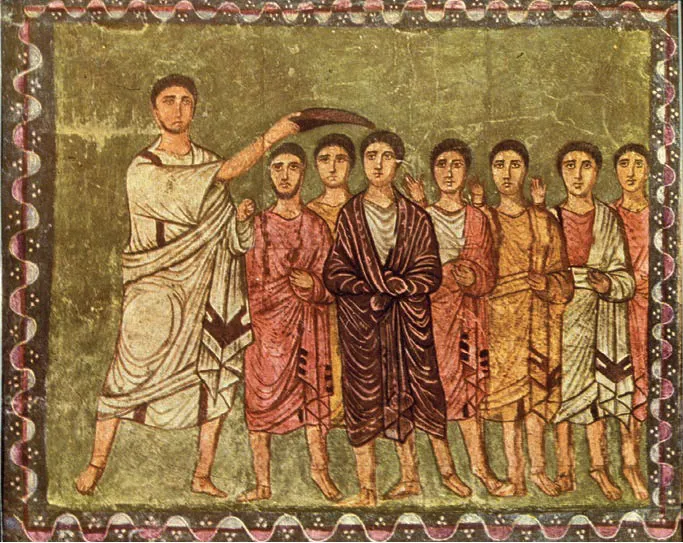

Our earliest picture of Jewish dress comes from the third-century synagogue of Dura-Europos on the Euphrates River, Syria. This fresco shows Samuel anointing David. But note how the dress is strictly Hellenistic and that no fringes are evident on the garments.

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.co

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.co

RE-CREATING THE CONTEXT

What basic elements are necessary if we are going to be diligent in building this “context of antiquity”? Three important elements contribute to rebuilding the New Testament context: the land, the history, and the culture. Every interpreter of the New Testament must have some mastery of each.

Knowing the Land

When Jesus moved through Galilee or traveled to Judea, he knew where he was. He knew the landscape, the roads, Hellenistic cities such as Scythopolis, and Jewish fishing villages like Capernaum. When Paul organized his missionary journeys, he had a good sense which cities would be strategic for the growth of the church. On his second missionary tour, Paul did not travel north to the region of the Black Sea for good reason. Instead, he headed west to Troas, which was a gateway to the major population centers of the Greek world. These places sound confusing to us. But they were crystal clear to someone like Paul. He could refer to Sardis as easily as we refer to Boston or London.

Such knowledge of geography—landscape, geology, climate, water resources, roads, settlement patterns, and political boundaries—is common among all societies. Most literature simply presupposes that its audience will know these details naturally. The Gospels refer to the Sea of Galilee without telling us its location. They also mention places such as Bethsaida and Cana as if they are familiar to us. The disciples of Jesus are known as “Galileans” when they are in Jerusalem (Acts 2:7), and this word alone carried loads of innuendo and cultural weight. It is the same reason today that Egyptians in Cairo make jokes about other Egyptians “from the south.” Everyone knows (supposedly) what an Arab from Al Minya is like!

Our acquaintance with the specifics of biblical geography will play an important role in how we understand the story. When Jesus moves from Judea to Samaria, we must not only know where Samaria ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- 1. Studying the New Testament

- 2. The Historical Setting of the New Testament

- 3. The World of Jesus In His Jewish Homeland

- 4. The Mediterranean World of the Apostle Paul

- 5. Sources for the Story of Jesus

- 6. The Story of Jesus

- 7. The Teachings of Jesus

- 8. The Gospel According to Matthew

- 9. The Gospel According to Mark

- 10. The Gospel According to Luke

- 11. The Gospel According to John

- 12. The Acts of the Apostles

- 13. Paul of Tarsus: Life and Teachings

- 14. The Letter to the Galatians

- 15. 1 and 2 Thessalonians

- 16. 1 Corinthians

- 17. 2 Corinthians

- 18. The Letter to the Romans

- 19. Colossians and Ephesians

- 20. Philippians and Philemon

- 21. The Pastoral Letters: 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus

- 22. The Letter to the Hebrews

- 23. The Letter of James

- 24. 1 and 2 Peter and Jude

- 25. The Letters of John

- 26. The Revelation of John

- 27. The Preservation and Communication of the New Testament

- Scripture Index

- Noncanonical Ancient Sources Index

- Subject Index