1

THE (NOT SO) SECRET SECRETS

Awareness about what is happening in the post–September 11, 2001, airline industry comes to each of us in different ways with varying intensity. One thing is certain: aviation in the United States changed forever after 9/11. Only now, over a decade later, is it becoming apparent how much. And I don’t just mean increased security measures during the flight check-in process. The entire aviation industry has changed radically over the past decade with serious risk and safety implications, and certain sectors continue to hope no one will “alarm the passengers.”

We know what happened on 9/11. And we also know about the economic instability of the aviation industry that followed. But what is less frequently discussed is why that instability really occurred and where the decisions made to address it are taking us now. Commercial airline executives want us to believe that the terrorist attacks caused the post-9/11 aviation industry downturn thus creating the current hypercompetitive environment. They use that logic to justify charging fees for everything from soft drinks and pillows to ticket changes and checked baggage. It’s a lucrative strategy. In 2011, the top airlines at the time (United, Delta, American, Southwest, US Airways, and Alaska) generated $3.4 billion in revenue from checked bags, up from $464 million in 2007, the year most airlines began the practice. These airlines also collected $2.4 billion from passenger penalty fees for rebooking nonrefundable reservations. Add in other incidentals and we find passengers paid an astonishing $12.4 billion in extra fees in 2011 alone—and this revenue is not taxed like traditional airfares.1

Yet, well before that crisp fall day in New York, informed insiders considered the aviation industry overdue for an adjustment. September 11 simply handed the already struggling airlines a popularly accepted excuse to downsize and adopt other changes executives had long wanted to implement. Major airlines used the event as an excuse to slash jobs, eliminating over two hundred thousand employees in the post-9/11 period, all the while eliciting sympathy and government support as one of the most visible images of America’s struggle against terrorism. As of 2010, airline employees continued to give up more than $12 billion a year in wages, benefits, pensions, and other work rules, while over 10,000 pilot jobs had disappeared at major air carriers.2 (Table 1 reflects total layoffs and hiring 2000–2012.)

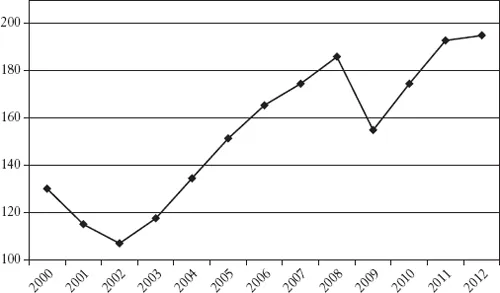

Like a clever magic trick, industry leaders used 9/11 as a foil, distracting the public by blaming the airlines’ financial slump on war, recession, terrorism, and travel scares such as SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), while pointing to rising fuel costs, greedy employees, aggressive labor groups, and frugal consumers’ bargain shopping online to explain airline insolvencies. Meanwhile, US air carriers quietly pocketed over $2 trillion in revenue between 2000 and 2012,3 and airline executives earned millions of dollars for themselves (fig. 1). Consider Jeffrey A. Smisek, president and CEO of United Continental Holdings, the company created after the United-Continental merger in 2010. Number 123 on the list of America’s highest-paid CEOs, Smisek earned $13.3 million in compensation in 2011, falling just behind Wall Street executives such as Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan Chase, Lloyd C. Blankfein of Goldman Sachs, and Vikram S. Pandit of Citigroup.4

You might think that staying out of bankruptcy was the primary job of an airline executive. However, in an odd twist of the bankruptcy process, on exiting Chapter 11 airline management teams typically keep between 5 and 10 percent of the company’s shares. CEOs often keep 1 percent just for themselves.5 That means managers are handsomely rewarded for getting their company out of financial messes they created in the first place. It is a nice payoff for stiffing creditors, wiping out shareholders, furloughing employees, and alienating passengers. Over the last several decades, this is where airline CEOs have gotten rich. United’s CEO Glenn Tilton received a pay package worth nearly $40 million in new shares and other compensation after the airline emerged from bankruptcy in 2005. Northwest’s CEO Doug Steenland received a package worth some $26.6 million when the company emerged from Chapter 11 in 2007. And the process continues to this day, unregulated.6

TABLE 1. Total number of pilots per US airline, 2000–2012*

FIGURE 1. US airline revenue in billions of dollars, 2000–2012. Source: Data from http://www.transtats.bts.gov/Data_Elements_Financial.aspx?Data=7.

In 2012, American Airlines and US Airways were negotiating a merger as well. Most industry analysts agree that American, the third-largest US airline, and US Airways, the fourth-largest, will eventually have to merge if they are to stand a chance of competing against the United-Continental and Delta-Northwest conglomerates. However, American’s CEO, Tom Horton, and his management team will profit more if American emerges from bankruptcy first, earning them somewhere between $300 and $600 million. Meanwhile, US Airways’ CEO Doug Parker’s contract has a change-of-control provision that could earn him more than $20 million if his airline is bought by another company and he is forced out.7

During this same period, when airline executives like Tilton, Smisek, Steenland, and their management teams were collecting record compensation, thousands of their airlines’ employees remained out of work. When challenged about this inequity, airline executives defended their managerial decisions and compensation strategies. Like the financial industry’s defensiveness about Wall Street’s executive bonuses paid just months after the $700 billion government bailout of the Street’s “troubled assets” in 2008, airlines justified the post-9/11 executive rewards as appropriate and necessary to attract and retain top performers.8 Are these high-priced, short-term managerial strategies—and the shady deals and organizational culture they foster—mere coincidence, or are there identifiable patterns between the business practices of these two boom-or-bust American industries?

Both finance and aviation have long histories of secret deals and political gamesmanship behind exorbitant financial wins and losses. As both industries became increasingly deregulated over the past few decades, a new type of manager took over the executive suites, and troubling evidence emerged of a managerial fixation on maximizing short-term profits for themselves at the expense of long-term company sustainability while disregarding the resultant systemic risks. The following chapters unpack the details of this confluence of events. For now, let us consider that if this pattern of risk taking brought Wall Street to the brink of collapse in 2008, might growing cracks in the airline industry related to self-serving risk taking be threatening air safety as well?

My review of government documents and accident reports, along with interviews with hundreds of aviation industry professionals, provides evidence that hidden fractures have been widening in the aviation industry in ways alarmingly resonant with patterns preceding the financial crisis of 2008.9 Contrary to the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) claim that “this is the golden age of safety, the safest period in the safest mode, in the history of the world,”10 we seem to be entering a period of unprecedented global risk. Perhaps US Airways Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, the pilot who landed his Airbus-turned-glider on the icy surface of the Hudson River, said it best when he spoke to Congress in 2009.11 Voicing concerns held by most veteran airline employees, he testified, “While I love my profession, I do not like what has happened to it.” US airline employees “have been hit by an economic tsunami.” Citing bankruptcies, layoffs, pension loss, pay cuts, mergers, and “revolving door management teams who have used airline employees as an ATM” as causes for the turmoil, Captain Sullenberger confided that he was “deeply worried” about safety and the industry’s future, claiming, “I do not know a single professional airline pilot who wants his or her children to follow in their footsteps.” With airlines no longer able to “attract the best and the brightest” to aviation careers, he worried that “future pilots” will be “less experienced and less skilled” with “negative consequences to the flying public—and to our country.” To avoid this, he insisted that “airline companies must refocus their attention—and their resources—on the recruitment and retention of highly experienced, well trained pilots,” making that a priority “at least equal to their financial bottom line.”12

Captain Sullenberger is not alone in expressing these concerns. The chaotic state of the post-9/11 aviation industry generated such widespread attention in Congress that the Government Accounting Office (GAO) was asked to investigate the implications of airline bankruptcies, mergers, loss of pension plans, and high fuel prices, and even consider re-regulating the struggling industry.13 One study claimed that “the airline bankruptcy process is well developed and understood” and went on to document the liquidation of employee pension plans, offering examples of the significant loss of benefits senior airline employees, such as Captain Sullenberger, will experience when they retire. Yet it nonetheless contended there is “no evidence” that bankruptcy “harms the industry.”14 Another report noted, “The historically high number of airline bankruptcies and liquidations is a reflection of the industry’s inherent instability.”15 However, the GAO failed to investigate the implications of this instability for employees or passengers. In fact, not one of the government’s reports considered the impact of this tumultuous climate of outsourcing, mergers, downsizing, furloughs, and changing work rules on employees, their job performance, risk, or airline safety.

What do I mean when I talk about risk and safety? Risk is commonly understood as a situation involving exposure to danger, harm, or loss. And safety is the process of controlling situations to minimize exposure to these hazards. How can managing risk and safety be a profitable process? In the nineteenth century, commercial trade in risk emerged as a commodity much like the exchange of timber, cotton, and tobacco. Marine insurance became the first form of risk management when merchants insured their cargo against “perils of the sea” and insurers sold these policies to each other for financial gain.16 Since then, shifting risk has become a lucrative business strategy.

As corporations began to amass extraordinary wealth, questions soon followed about whether industrial profit making should come from assuming risk, as with marine insurance, or from reducing it through better work practices.17 In response, three risk-related roles emerged in the corporate industrial economy: the entrepreneurial “risk-maker” who jumpstarts the industrial process, the financial “risk-taker” who invests in corporations and their stock, and the managerial “risk-reducer” who rationally supervises economic production.18 Over time, neoliberalism, and the increasingly deregulated marketplace associated with it, blurred the boundaries between these risk management roles, as executives, previously risk-reducers, now adopted risk-maker strategies throughout corporate America. I will return to this important managerial shift and its implications for risk and safety.

Obviously, no airline flight, business decision, or financial investment is 100 percent risk free. So what then are acceptable levels of risk? It depends. To determine which air safety regulations to adopt and which situations to risk, the FAA, nicknamed the “tombstone agency” for basing their decisions on body counts,19 conducts a cost-benefit analysis. “The basic approach taken to value an avoided fatality,” the FAA explained, “is to determine how much an individual or group of individuals is willing to pay for a small reduction in risk.”20 For instance, the FAA might weigh the risk of a fatal accident occurring every year by considering the loss of the aircraft ($100 million) and the death of its one hundred passengers, each life valued at $3 million ($300 million) versus the cost to airlines to fix a reoccurring mechanical flaw ($10 million) in every airplane of this type in service (1,000).21 In this example, the avia...