![]()

Chapter 1

The Difficult Birth of Honeybee Colour Vision

Scientists . . . need to explain what is being done and why, ensuring that conflicts of interest are revealed, and that it is clear what knowledge is secure and what is not. [my emphasis]

(Sir Paul Nurse, Anniversary Address, 2015)

We expect to see colours everywhere, and use them to distinguish, for example, ripe fruit. Not to see colours as constant would be very worrying, but we depend also on a peculiar property of human colour vision. White or coloured surfaces or lamps do not change colour with changes of intensity over many orders of magnitude: for example, from moonlight to bright sunlight (a factor of 107). A neutral filter is said to be neutral because it absorbs some of the light but leaves constant the composition of the light, as humans perceive it.

Bees have excellent eyes, as anyone can infer when watching them forage. Throughout the 19th century, a number of competent scientists used coloured and neutral grey filters to test whether bees had colour vision (Forel, 1908; von Hess, 1912). They were aware that people who were totally colour-blind could distinguish between two colours by their relative brightness. They used the attraction of insects to light, called phototaxis, and found that bees walking out of a dark box preferred blue when the test colours appeared equally bright, but the bees’ preference could be shifted away from blue when other colours were simply made brighter. Bees obviously confused colours with brightness in a way that was no different from colour-blind people. This seemed a straightforward demonstration that bees did not have true colour vision.

A young boy, John Lubbock (later Sir John, later Baron Avebury, MP for Westminster), who lived next door to Charles Darwin, was urged by the old scientist to observe nature and experiment, when he left Eton School to join his father’s London bank. From 1874 onwards, John published his observations on ants, bees and wasps. He found that bees have an order for spontaneous preference: blue, then white, yellow, green and orange, while red was generally the least preferred. At the time, no one recognized that, apart from yellow, this was a rough scale of diminishing content of blue. He found that hungry bees could learn which of several colours indicated honey (Lubbock, 1881). He understood that observing bees on flowers told one very little. To discover what bees actually detected, it was essential to train them on a target, or discriminate between two targets, then test them. The essential technique was to move the colour and the reward with it while the training was in progress, so that the bees became accustomed to search for the colour in several places. Then, in subsequent tests with other colours, they made an effort to search; in fact, they were trained to search. For the first time, it was noticed that they took a much longer time to learn, because they could no longer use the fixed local landmarks or odours to head straight to the reward. Lubbock’s popular books reinforced the view that bees distinguish colours like humans do, but that was not the academic opinion at the time.

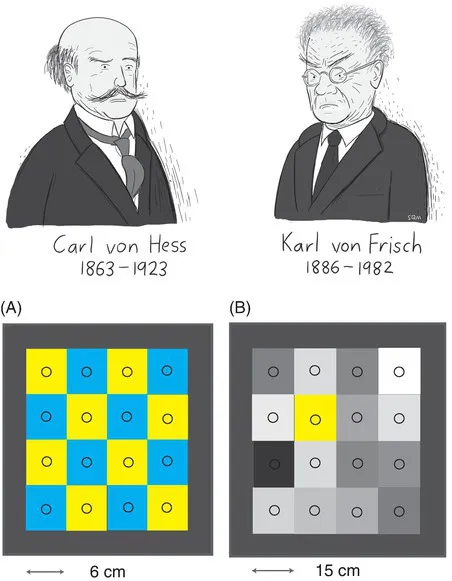

In 1912, Carl von Hess, Professor of Ophthalmology at Münich University and Director of the Münich Eye Clinic, published a well-researched book on the comparative physiology of vision. As a result, he was regarded as a sound authority on the whole topic. He had newly arrived from Würzburg, a powerful professor at the height of his powers, which meant a lot in a German university at that time. For some years, at the Naples Marine Laboratory, he had collected data on a variety of animals, including fish. There his findings had been challenged by a young assistant called Karl von Frisch. Hess had shown that several species were colour-blind in the phototaxis response. Octopus and other cephalopods reacted similarly in his apparatus. They went to the brightest place irrespective of colour.

In his book, as a true scientist, Hess began his account of honeybee vision with his own phototaxis experiments in which freely flying or walking bees could choose between two compartments with coloured lamps of controlled brightness. With colours of similar intensity, he validated the earlier demonstrations that bees in a dark box preferred blue, but on increasing the brightness they could change their preference to another colour. Later, Hess showed that in the escape response bees are attracted to ultraviolet (UV), which was a signpost to the escape route to the sky. Later still, Menzel and Greggers (1985) showed that when bees move out of darkness, they detect the total photon capture including green receptors. Therefore, total summation of receptors is possible, as well as specific attraction to UV, in the escape response and in the righting response, which is a directional response to UV that keeps them in level flight. This shows how easily we may be confused, even before we have reached the foraging behaviour.

In his book, Hess discussed much of the vast amount of information collected in the 19th century about visits of bees to flowers, and questioned the universal belief that they distinguished flower colours. All observations were about successes of the bees, so any reasonable theory of how they succeeded would have fitted the evidence. In all this mass of data on foraging, even by John Lubbock, there were no studies where colour and brightness were separately tested with foraging bees.

Hess, however, found more secure evidence, which modern authors usually fail to quote. Between 1885 and 1906, in a long series of experiments with coloured artificial flowers, Felix Plateau, Professor of Zoology at Ghent University and a son of the famous mathematician, found that shapes or colours of artificial flowers could be changed with little effect, and were not critical for the bees to find the reward. Plateau concluded that bees used odour, not colour, as the cue (Plateau, 1885–1899; cited in Forel, 1908).

Auguste Forel, a medical professor and entomologist at Zürich, heavily criticized Plateau. Forel found that odours or vision were not essential guides, but the bees used surrounding landmarks that included flowers. The odours, colours and shapes of flowers were cues only in so far as they were consistent parts of the scene. Forel used Professor Plateau’s own data as evidence against his conclusions. There is no better way to demonstrate the weakness of an intuitive leap from the safe ground of data to an apparently obvious but incorrect conclusion. After 50 pages of fierce criticisms, Forel accepted Plateau’s data but not the false conclusions.

Hess must be given credit for quoting in his book a suggestion by Forel that bees should be trained to go to a colour, and then tested with that colour versus other colours and against various shades of grey. The criterion was still based on performance and inspired by human vision. In fact, whether or not bees could distinguish colours from grey would not reveal much about bee vision; because they could not detect grey. However, this experiment had to wait.

In 1898, Albrecht Bethe, Professor of Physiology at the University of Strasbourg, showed that bees apparently did not recognize even familiar objects such as their hive, or a tree, as separate things. In fact, for centuries beekeepers had known that the bees did not recognize their own hive if it was moved only a metre sideways, whatever its colour. The fact that these distinguished professors experimented and argued for years should add some support for their main conclusion that the bees did not see the shapes or colours of flowers in the way that humans do. Hess also reviewed this research and concluded in his book that essential evidence for colour vision of bees was lacking. Later reviewers, if they mentioned Hess at all, said incorrectly that he referred only to the attraction to coloured lights.

We now know that bees are not interested in the shapes or colours of flowers or of any other thing. They learn a few landmarks that bring them to the place where they find nectar or sugar solution. If the experiment involved a change in flower colour or shape, they scarcely noticed, as Plateau found, but if their familiar landmarks were moved or hidden, they went away and looked elsewhere, making it difficult to discover what they had learned.

Too late to be in the book by Hess, Lovell (1910) showed that bees discriminated between colours irrespective of the intensity of illumination, and they could also learn to avoid a particular colour. Also in the USA, a remarkable Chicago schoolmaster, Charles Turner (1910) displayed a colour or pattern on the outside of a small box with a reward of sugar inside, and a different colour or pattern on a similar box with no reward. He changed the positions of the boxes at intervals to make the bees examine them irrespective of the exact place. The bees learned to look for the boxes and ignore the local landmarks. This experimental strategy made possible all the subsequent discoveries about bee vision of pattern and colour.

On the other hand, bees rewarded at a fixed place learned the local landmarks after a single reward. On their return they never made an error, but they did not reveal what they had learned because, when they were given unfamiliar tests, they went away or simply started to learn the landmarks afresh. Bees had to be trained to search before they could be tested with a variety of unfamiliar targets.

In his book, Hess did not distinguish clearly between results from foraging bees and those from bees in the phototactic response. At the time, there was no clear understanding that a bee could distinguish colours in one kind of behaviour but be colour-blind in another situation. This was the missing thought that could have helped to distinguish different strands in the data.

Karl von Frisch (1886–1982) was from an intellectual family based in Vienna in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His maternal grandparents were Jewish converts to Catholicism. This generation of professors, Bethe, Chun, Anton Dohrn, Eimer, the Exners, Goldschmidt, Haeckel, von Uexküll, and Oscar and Richard Hertwig, left a huge legacy of wonderfully accurate descriptions of the anatomy and physiology of invertebrates, often based on research in Naples, bringing Mediterranean fauna into European classical zoology.

Young Karl was appointed by a relative, Professor Richard Hertwig, as an assistant in the Zoology Department in the University of Münich in 1910 at the age of 24. Like Hess, he had investigated the colour vision of fish at the Naples Marine Laboratory, but he trained fish to come to a coloured target and then, as in the test for defects in human colour vision, he tested them with various shades of grey papers, finding that they distinguished the colour. Also at Naples, Hess found by the phototaxis method that they were colour-blind (not necessarily the same species). At the time, no one guessed that two different kinds of vision of colour could exist in one animal. From that time on, they were fierce antagonists: Frisch even visited Naples in 1913 just to prove that cephalopods have colour vision, and contradict von Hess, but he failed in that effort, and never mentioned it again (Dröscher, 2016).

The conclusion by Hess, that bees do not have colour vision like humans, obviously stimulated Frisch to disprove the senior professor, a strategy that gives a young man a good start. He was able to use the family holiday chalet at the idyllic village of Brunnwinkl in the Austrian Alps for his own work, training bees and fish, then testing their senses. Several members of his family, including his uncles Sigmund (Physiology) and Karl Exner (Physics), both professors at Vienna, helped as his assistants there. Working through three successive summers, he was able to collect a vast amount of data by counting arrivals of trained bees at black or grey feeding tables. Almost certainly he knew of the work on colour vision of bees by Turner and by Lovell, and cited the book by Lubbock. He quickly adapted the techniques used by Hess and Turner (with a reference to them) and started a long series of tests on trained bees with his own unique method developed for fish, which for some strange reason, has never been repeated, even by his own students.

Von Frisch trained bees for several days to come to a single coloured paper laid flat on a table in sunlight and then tested with it placed on a panel of 15 grey papers (Fig. 1.1B). It was a crucial choice of experimental arrangement. If Frisch had trained bees to discriminate between two colours and then tested with all colours and grey levels separately, he would have immediately revealed a lack of colour vision of the human type.

In 1914, it seemed obvious that the test for colour vision with a colour versus all grey levels would prove or disprove colour vision, but that was a test for defects in the colour vision of man. It was just bad luck that the bees distinguished green contrasts at edges and measured the average blue content of areas of grey.

From the start, Frisch was absolutely convinced that bees trained on a certain colour distinguish the training colour from other colours, as research of others had shown:

Dass sich die Insekten an gewisse Farben gewöhnen, auf sie ‘dressieren’ lassen und sie von anderen farben zu unterscheiden vermögen, ...