eBook - ePub

Positive Psychology and Change

How Leadership, Collaboration, and Appreciative Inquiry Create Transformational Results

Sarah Lewis

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Positive Psychology and Change

How Leadership, Collaboration, and Appreciative Inquiry Create Transformational Results

Sarah Lewis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Positive Psychology and Change explores how areas of positive psychology such as strengths, flow, and psychological capital can be applied to the everyday challenges of leading a dynamic and adaptive work community, and how collaborative group approaches to transformational change can be combined with a positive mindset to maintain optimism and motivation in an unpredictable working environment.

- Articulates a unique vision for organizational leadership in the 21st century that combines positive psychology, Appreciative Inquiry (AI), and collaborative group technologies

- Focuses on four specific co-creative approaches (Appreciative Inquiry, Open Space, World Café and SimuReal) and the ways in which they surpass traditional methods for organizational change

- Explains the latest theory, research, and practice, and translates it into concrete, actionable ideas for meeting the day-to-day challenges of effective and adaptive leadership and management

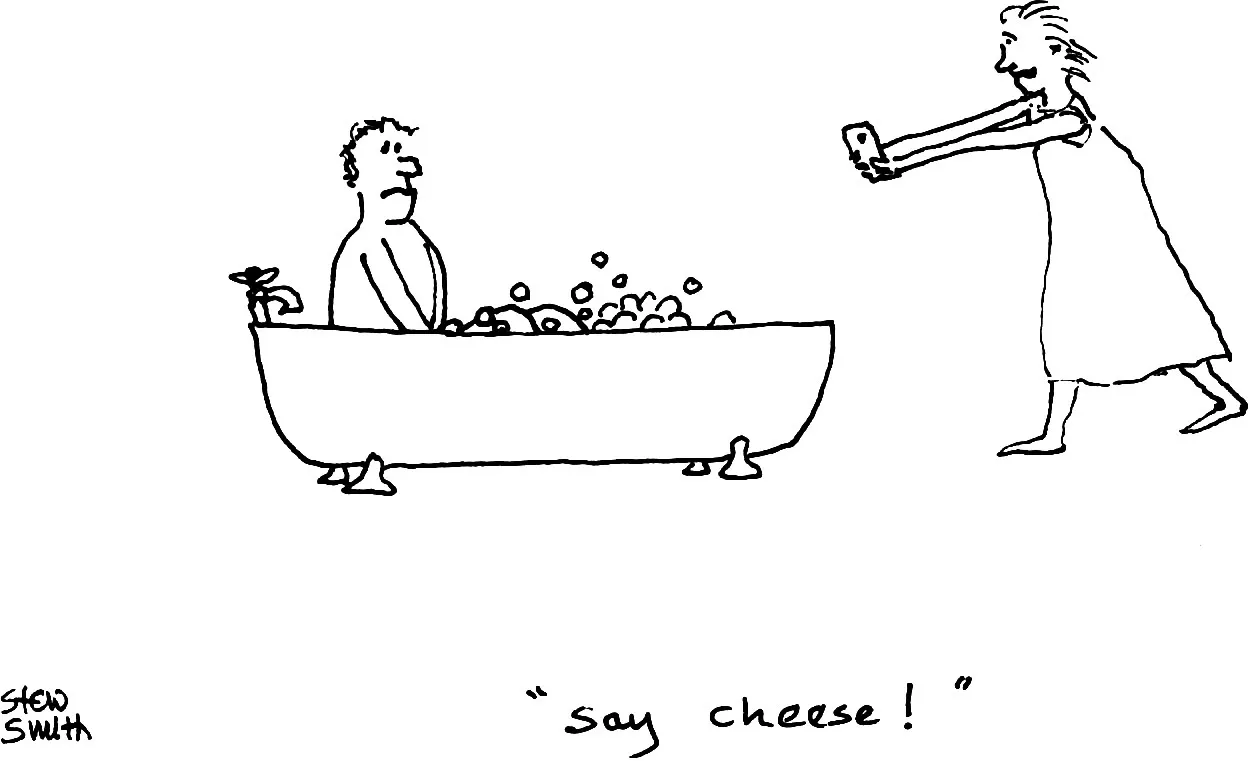

- Includes learning features such as boxed text, short case studies, stories, and cartoons

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Positive Psychology and Change an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Positive Psychology and Change by Sarah Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Leadership. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Legacy of Twentieth-Century Ideas about Organizational Change

Picture the scene. I’m watching Boardwalk Empire on DVD with someone who came of age well into the twenty-first century. We get to the scene where a young “gofer” is asked his name by another gofer. He replies, “Al, Al Capone.” My young friend says, “Wasn’t he a real person?” I don’t answer immediately, pausing while I wait for a suitable gap in the dialogue. She answers her own question: “Yes he was.” She reads a few sentences about Al Capone from her iPhone. She then asks, “Are any of the other characters real?” “I don’t know,” I say. A slight pause and then, “What’s Nucky’s proper name?” “Enoch.” She looks up “Enoch Thompson” on the phone. “Oh yes, he’s real too.” Throughout our programme-watching her phone whistles at her intermittently, and each time she attends for maybe 30 seconds, smiling, pouting, texting.

There is nothing new in this account, and everything. My dinosaur ways, such as watching a DVD rather than viewing content direct from the internet, my assumption that all relevant information is present in the vision and sound on the screen, my distance from my electronic “work” devices (it is the weekend, my mobile phone is in a bag somewhere, undoubtedly still on silent from the last meeting on Friday), all mark me out as essentially from the pre-digital age. My young friend engages with the world differently. Her phone lives in her hand. She is a cyber-person at one with the internet. It is always on and so is she. Any curiosity, mild or strong, can be instantly gratified. When she cooks a meal, before we are allowed to eat it a picture must be sent to friends. Arrangements with friends are so fluid as to be at times indiscernible to the naked eye as commitments. Fraught and loaded conversations with the boyfriend about “the state of the relationship” are conducted in 20-word text bites. She truly lives in a different world to me.

Introduction

My young friend and her colleagues are the inhabitants and creators of future, as yet unrealized, organizations. These organizations need to be fit for the changing world. At present we are in a state of transition from the solid certainties of the latter half of the twentieth century (the programme is shown once, at 9.00 p.m. on BBC1 – make it or miss it) to the increasing fluidity of the twenty-first century (watch it now, watch it later, on the TV, on a tablet, legally or illegally – whatever, whenever). This isn’t only the case in the media world; it can be argued that the organizational development world is in a similar state of flux.

Many of the organizational development approaches and techniques that are in common use in organizations today were developed in the1940s and 1950s. Most of the theorists were male, European and living in America. Their ideas are located in a specific time and context. Their ideas and theories are not timeless truths about organizations and organizational life; rather they are a product of, and are suited to, their time and context. This chapter examines the key features of these organizational development models and their influence on current beliefs about how to produce organizational change. First though, a reminder of how much the world has changed since the 1940s.

A Changing World

The jury is still out on whether the recession of the last six years (as experienced by most of the Western world at least), is a temporary glitch in the upward path of increasing productivity and affluence, or the dawning of a new economic world order. What it has brought into sharp unavoidable focus is the interconnectedness of the world, and the complexity of that interconnectedness. Michael Lewis’s books The Big Short (2010) and Boomerang (2011) spell out in words of few syllables how the US property and financial markets came crashing down, bursting property bubbles all over Western Europe, and bringing other markets down with them. One of the many insights to be drawn from this calamitous tale is that the level of complexity developed in the money market obscured the connective links between actions. One of the few who seemed to understand something of this before the event is Nassim Taleb, who, in his book The Black Swan (2008) (a somewhat more challenging read than Michael Lewis, and not for the faint hearted), essentially says that the real threat isn’t what can be predicted, precisely because we can prepare for that; it is what can’t be predicted. And his argument essentially is that the degree of fundamental unpredictability, for organizations, is growing partly because of the increasing level of complexity and interconnectivity of the world at large.

Unpredictability and complexity create challenges for change initiatives. When there is a high degree of unpredictability and complexity it becomes more obvious that not all the variables relevant to a situation can be known. Not all the likely consequences of actions can be predicted in their entirety, and the effects of our actions can’t be bounded. Cheung-Judge and Holbeche note that “overall the challenges for leaders relate to dealing with the complexity, speed and low predictability of today’s competitive landscape” (2011, p. 283). And yet we all, leaders and consultants, frequently act in the organizational change context as if we can control all the variables and predict all the consequences of our actions. A contributing factor to this misplaced sense of omniscience is that many of our change theories and models are predicated on the idea that organizational change is predictable and controllable. To understand this, we need to recognize that many of them are the direct descendants of ideas developed over 60 years ago, when the world was a very different place.

The Roots of Many Change Models

In the 1940s Europe was busy tearing itself apart in the second large-scale conflict of the century. It managed to drag in most of the rest of the world through alliance and empire as the war ranged over large parts of the globe. Every continent (barring the South Pole) and almost every country was involved. The German Nazi party gave itself the mission of purifying the German race by removing various Nazi-defined undesirable or foreign elements that lived among them. This desire to eradicate perceived threat was focused mainly on the large German and later Polish and other annexed countries’ Jewish populations, but it was also aimed at homosexual men, Gypsies, and the mentally deficient. As the reality of the Nazi ambition became apparent, many under threat sought to leave Europe. America was a place of sanctuary before and during the war for those under threat of death, particularly the European Jewish population.

The genocidal intent of the Nazis and the industrialization of death through the extermination camps were a horrific and terrifying new reality in the world of human possibility. After the war the phrase “never again” encapsulated the ambition of many to understand and prevent such a tragedy from ever happening again. Many people devoted their remaining lives to trying to understand how it was possible for people to persuade themselves that such ambition and activity was not only acceptable but desirable and to be actively pursued. For some this expressed itself in an interest in understanding group dynamics. Organizations are a particular expression of social grouping. One German American Jewish refugee in particular wanted to understand how what had happened had happened, and more particularly, how to prevent it happening again.

Kurt Lewin was an immigrant German Jewish psychologist who found employment at Cornell University and then MIT. An applied researcher, he was interested in achieving social change and he developed the research methodology known as action research as a way of creating practical and applicable knowledge. As part of his work and research, Lewin developed models to understand and effect organizational change which still reverberate in organizational thinking. His three-step model of organizational change (1947), namely, unfreeze, change, freeze, is at the base of many more recent change models. This model understands organizations to exist in an essentially stable state, one that is periodically interrupted by short episodes of disruptive change. The use of the “frozen” image to describe the before and after state around the period of change suggests not so much stability as a deep stolidity, like a block of ice. This suggests that change is not something that might grow internally from within the organization, but rather something external that needs to be applied to organizations to encourage change, to create the necessary unfreezing of the present state to allow change to happen. Lewin also described these external forces as a force field, and advocated force field analysis.

He suggested that at any point a stable organizational state is held in place by a force field of restraining and driving forces (1947). The field is revealed through the creation of a vector analysis diagram of any particular context, identifying the pertinent forces. The restraining forces, things such as organizational norms, structure, and so on, he argued, hold the situation in place. Driving forces, such as managerial desire or the consequences of not changing, are those that push in the direction of the desired change. While they are in balance the situation is in stasis. To achieve change, he arg...