Beyond the Bubble Test

How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning

Linda Darling-Hammond, Frank Adamson

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Beyond the Bubble Test

How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning

Linda Darling-Hammond, Frank Adamson

About This Book

Performance assessment is a hot topic in school systems, and educators continue to analyze its costs, benefits, and feasibility as a replacement for high-stakes testing. Until now, researchers and policymakers have had to dig to find out what we know and what we still have to learn about performance assessment. Beyond the Bubble Test: How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning synthesizes the latest findings in the field, and not a moment too soon.

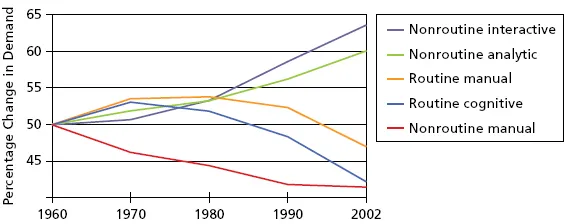

Statistics indicate that the United States is in danger of falling behind if it fails to adapt to our changing world. The memory and recall strategies of traditional testing are no longer adequate to equip our students with the skills they need to excel in the global economy. Instead teachers need to engage students in deeper learning, assessing their ability to use higher-order skills.

Skills like synthesizing information, understanding evidence, and critical problem-solving are not achieved when we teach to multiple-choice exams. Examples in Beyond the Bubble Test paint a useful picture of how schools can begin to supplement traditional tests with something that works better. This book provides new perspectives on current performance assessment research, plus an incisive look at what's possible at the local and state levels.

Linda Darling-Hammond, with a team of leading scholars, bring together lessons learned, new directions, and solid recommendations into a single, readily accessible compendium. Beyond the Bubble Test situates the current debate on performance assessment within the context of testing in the United States. This comprehensive resource also looks beyond our U.S. borders to Singapore, Hong Kong, and other places whose reform-mindedness can serve as an example to us.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: The Rationale and Context for Performance Assessment

I am calling on our nation’s Governors and state education chiefs to develop standards and assessments that don’t simply measure whether students can fill in a bubble on a test, but whether they possess 21st century skills like problem-solving and critical thinking, entrepreneurship and creativity.—President Barack Obama, March 2009

To be helpful in achieving the learning goals laid out in the Common Core, assessments must fully represent the competencies that the increasingly complex and changing world demands. The best assessments can accelerate the acquisition of these competencies if they guide the actions of teachers and enable students to gauge their progress. To do so, the tasks and activities in the assessments must be models worthy of the attention and energy of teachers and students. The Commission calls on policy makers at all levels to actively promote this badly needed transformation in current assessment practice. . . . The assessment systems [must] be robust enough to drive the instructional changes required to meet the standards . . . and provide evidence of student learning useful to teachers.New assessments must advance competencies that are matched to the era in which we live. Contemporary students must be able to evaluate the validity and relevance of disparate pieces of information and draw conclusions from them. They need to use what they know to make conjectures and seek evidence to test them, come up with new ideas, and contribute productively to their networks, whether on the job or in their communities. As the world grows increasingly complex and interconnected, people need to be able to recognize patterns, make comparisons, resolve contradictions, and understand causes and effects. They need to learn to be comfortable with ambiguity and recognize that perspective shapes information and the meanings we draw from it. At the most general level, the emphasis in our educational systems needs to be on helping individuals make sense out of the world and how to operate effectively within it. Finally, it is also important that assessments do more than document what students are capable of and what they know. To be as useful as possible, assessments should provide clues as to why students think the way they do and how they are learning as well as the reasons for misunderstandings. (p. 7)