![]()

Part I

An Overview of Nonprofits’ Legal Needs

![]()

Chapter 1

What Good Counsel Can Do for Nonprofits

This chapter surveys the broad landscape of nonprofit organizations, clarifying often-confusing terminology and pinpointing what differentiates nonprofits from for-profits (hint: it’s not whether or not the entity makes a profit). The chapter then introduces the main legal concerns that set nonprofits apart from other kinds of business entities. Different from most other books about nonprofit law, it goes on to describe other kinds of business laws that apply to all entities—whether nonprofit or for-profit—much to the surprise of many nonprofit executives, who may have the erroneous impression that their organizations are not only tax exempt but law exempt! The wide array of laws applicable to nonprofits, the similarities and differences between how business laws apply to nonprofits and other kinds of business entities, and how compliance with applicable laws can help the organization make good on its mission, are recurring themes throughout the book.

Board members, management and incoming counsel may benefit from reading together the three chapters in Part I.

Because of the broad sweep of the nonprofit sector, generalizations about legal needs are hard to make. The sector encompasses large institutions and smaller ones; some that predate the founding of our nation and some that are still in the process of being formed; some that attract nationwide attention and others that labor in relative anonymity; some with an international footprint and some that operate out of the founder’s living room.

What Legal Needs Do Nonprofits Have in Common?

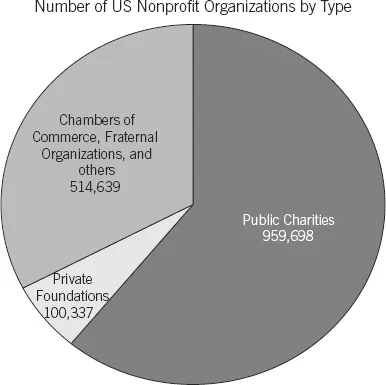

The primary focus of this book, and the largest category of nonprofit organizations, is the million or so public charities that are tax exempt under Section 501(c)(3) of the United States Internal Revenue Code. These organizations include hospitals, museums, private schools, religious congregations, orchestras, public television and radio stations, soup kitchens, and certain types of foundations, such as organizations that prevent cruelty to children or animals or foster a cleaner environment. (Although private foundations and some other types of nonprofit organizations under Section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code face legal issues that are similar in many respects to public charities, there are enough differences that it would not be practical to identify each one in this book.) For convenience, this book will use the term nonprofit organizations, or nonprofits, to refer to Section 501(c)(3) public charities.1

Other kinds of nonprofit organizations, such as chambers of commerce, fraternal organizations, or civic and athletic leagues, may be tax exempt, but contributions to them are not tax-deductible.

Figure 1.1 may help readers visualize these various categories.

⇒ Practice Pointer

This volume is aimed at Section 501(c)(3) organizations that qualify as public charities.

Confusion abounds regarding terminology. Tax-exempt organizations, nonprofit organizations, and not-for-profits are often used interchangeably but, technically speaking, these terms have different meanings. The term tax-exempt organization refers to organizations that are exempted from certain kinds of taxes by the federal, state, and local governments. The term nonprofit organization is broader, and may refer to all kinds of entities that exist not to make profits for owners but for a broader purpose. State laws, under which nonprofits are organized, generally prohibit the organizations from making distributions to their founders or insiders, or otherwise operating primarily for the financial benefit of any private party. Instead of paying dividends to shareholders or creating other economic value for private persons, nonprofit organizations plow the net proceeds (that is, profits) from their operations back into their mission-related activities, in furtherance of their stated public purpose.

Different states use different terminology—some use nonprofit, some use not-for-profit, and others use other terminology and different criteria for organizations to qualify as nonprofit corporations. Further confusing matters, experts in the field often use the word charity to refer to all kinds of 501(c)(3) organizations, including organizations with scientific research, culture, or the advancement of religion as their mission, even though the word charity, in common parlance, connotes an organization that primarily serves the poor.

For purposes of this book, the words nonprofit or nonprofit organization refer to organizations that are recognized by their states’ laws as nonprofits, that are publicly supported, and that have obtained recognition of tax exempt status by the federal government under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.

The public charities that are the subjects of this book fall into eight major areas of focus:

1. Arts, culture, and humanities—such as museums, symphonies and orchestras, and community theatres. These may include everything from the renowned Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the tiny Tidewater Classic Guitar Society in Norfolk, VA.

2. Education and research—such as private colleges and universities, independent elementary and secondary schools, and noncommercial research institutions. This category includes multi-billion dollar Ivy League universities as well as small local or regional high school dropout prevention programs such as Seven Lakes High School’s Project Graduation in Cut Off, Louisiana.

3. Environmental and animals—such as zoos, bird sanctuaries, wildlife organizations, and land protection groups. The National Geographic Society in Washington, DC falls into this category, as do local organizations such as Friends of the Verona Street Animal Shelter Inc. in Pittsford, NY.

4. Health services—such as hospitals, public clinics, and nursing facilities, mental health and crisis intervention clinics. Examples abound, large and small, from the enormous Kaiser Foundation in Portland, OR to the Trinity Group Homes for addiction treatment in Coeur d’Alene, ID.

5. Human services—such as housing and shelter, organizers of sport and recreation programs, and youth programs. Nonprofits in this category include the mighty Legal Services Corporation of Washington, DC, which takes in and expends some $350 million a year providing legal services to indigent people, and the local food pantries that feed the hungry throughout our nation.

6. International and foreign affairs—such as overseas relief and development assistance, including Feed the Children (Oklahoma City, OK) and the Hands Across the Border Foundation, a small nonprofit in Boulder, CO dedicated to improving cultural understanding among citizens of the border states of Mexico, Canada, and the United States.

7. Public and societal benefit organizations—such as private and community foundations, and civil rights organizations. The ACLU, is one example; the Special Equestrians of Vero Beach, FL, which provides educational and therapeutic horseback riding for the physically and mentally challenged is another.

8. Religion-related charities—this includes faith-based programs and congregations large and small.2

Clearly these organizations are serving a tremendous range of interests. What do they have in common by way of legal needs? The common threads are their missions, their fiduciary duties, and their tax-exempt status. Let’s examine each of these common elements in turn.

Laws About Mission

A nonprofit’s mission is its reason for being. Charitable nonprofit organizations are intended to serve a public purpose rather than provide a private benefit to individuals, corporations, industries and others. It follows that the organization’s assets and activities must be devoted to the public purpose for which it was incorporated. Everyone in a leadership role must deeply understand that the purpose of the organization is charitable, and that it must engage primarily in activities that accomplish one or more of its public purposes. Deviating from its mission can expose the organization and the people within it to serious consequences: possible personal liability for directors and officers for breach of fiduciary duty; possible removal of board members from service; state Attorney General’s action to restrain the organization from carrying on unauthorized activities; reputational and monetary costs to the organization; and, in extreme cases, revocation of tax exempt status or even revocation of charter.

Many organizations, their boards, and their staff are confused about what the mission is and how to identify it. Technically the mission is what the organization has told the IRS its mission is in its application for tax-exempt status, as well as what is reflected in the organization’s governing documents (its articles of incorporation and bylaws). The organization may well have updated or amplified its mission statement at board meetings or in publications, but if these updates are inconsistent with the original statement of mission, the changes do not officially change the federal tax-exempt purposes unless the IRS is formally notified. Some organizations have evolved to the point where their stated mission may be unrecognizable; such organizations would do well to consult with qualified counsel to help them update IRS filings to redefine the mission. They may also need to amend their certificate of incorporation, or bylaws, if the purpose clause included there is not written broadly enough to encompass the current activities of the organization.

In all cases, a critical job of an organization’s general counsel is to continuously remind trustees and management of the centrality of the organization’s mission in all decisions affecting the expenditure of organizational resources.

Laws About Fiduciary Duties

Leaders of the organization—whether they are trustees, officers, or other key players—must know and observe their fiduciary duties under state law, including:

1. The duty of care, which requires familiarity with the organization’s finances and activities and regular participation in its governance.

2. The duty of loyalty, which requires directors and officers to act in the interest of the corporation and to avoid or disclose conflicts of interes...