![]() Case Studies

Case Studies![]()

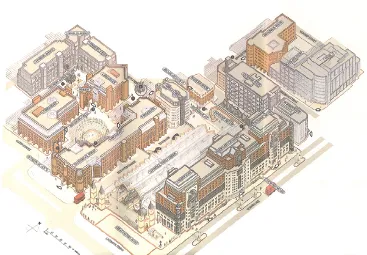

Broadgate

LOCATION: CITY OF LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM

DATE: 1985–91 (EXCEPT 201 BISHOPSGATE AND THE BROADGATE TOWER)

SIZE: 11.7 HECTARES (29 ACRES)

Situated on the fringe of the City of London, the Broadgate development transformed a site comprising a former train station and an adjacent operational station into a major new financial district.

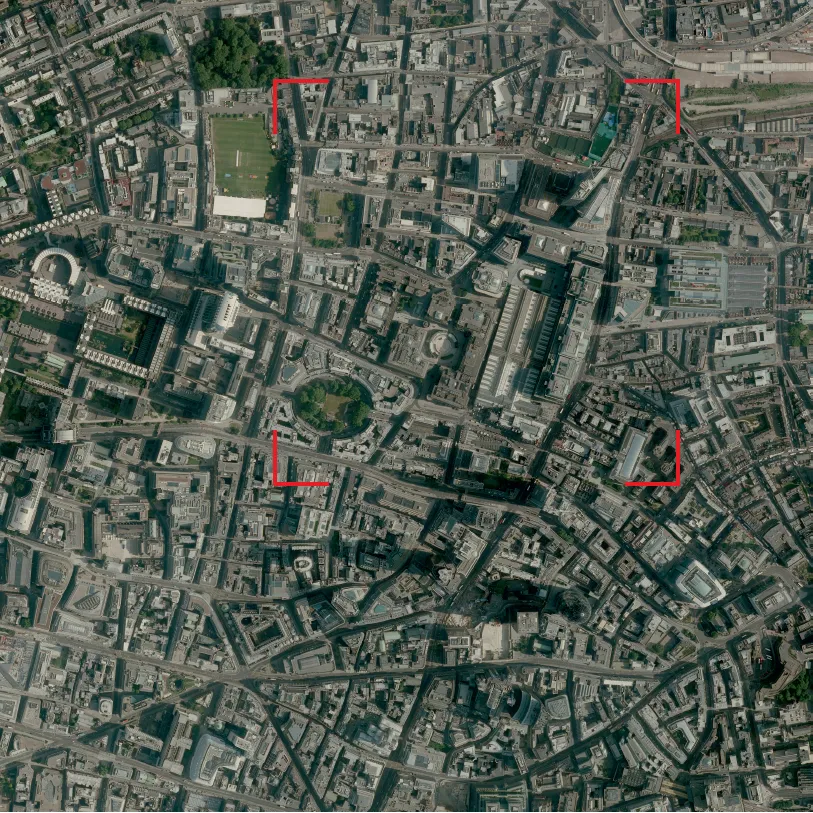

Like many other capital cities, the centre of London is served by a ring of terminus stations that connect the busy core with its direct surroundings and the national rail network. Historically, the stations were built by private operators, Euston Station being the first to open in 1837. Because of competition between these operators and the separate use of tracks and real estate, a number of stations were built almost adjacently – one extreme example being King’s Cross, St Pancras and Euston Stations, all situated within walking distance of one another. Operation of the railways was nationalised following the 1947 Transport Act, and growing financial pressures, coupled with changes of traffic and transport patterns in the second half of the 20th century, led to a multitude of service alterations and station closures. In the 1990s, the operation of trains was returned to the private sector, while the management of the tracks and stations remained in public hands, latterly under the name Network Rail.

Broad Street Station, a passenger and goods station, was built in 1865 on the northeastern corner of the City of London as terminus of the North London Railway network. After a period of initial success and several expansions, the station began to suffer from a downturn in usage in the early 20th century, a shift due mainly to the growth of bus, tram and tube networks. Damage during the Second World War did not improve the situation and by 1985 – one year before its final closure – only 6,000 passengers were using Broad Street Station every week. The situation for the directly adjacent Liverpool Street Station was very different: opened to the public in 1875 as terminus of the Great Eastern Railways and as a replacement for Bishopsgate Station, its operations were driven by a different set of destinations less challenged by the growth of the local public transport network. Though the station had been in urgent need of renovation and reorganisation since the 1970s, passenger flows were still steadily increasing. Today, Liverpool Street Station remains an important interchange between underground, bus and train services, and after Waterloo and Victoria is the capital’s third busiest train station.

The development of the Broadgate project happened in several phases but, in terms of architectural and personal initiative, the construction of 1 Finsbury Avenue – although financially a separate operation – can be considered the starting point. Built between 1983 and 1985 by the developer Rosehaugh Greycoat Estates on the site of Broad Street Station’s former goods yards and adjoining buildings, and designed by Peter Foggo of Arup Associates, this elegant and highly successful low-rise office building appeared as a vision of what the market wanted. The design, acclaimed for its large floor plates and generous interior atria, provided an appropriate urban response to the quandary posed by the run-down neighbourhood on the neglected fringe of one of the world’s wealthiest financial districts. Although located just outside the traditional City square mile, the building was able to meet the requirements of the financial service occupiers whose businesses were about to change as a result of the ‘Big Bang’ deregulation of the financial markets.

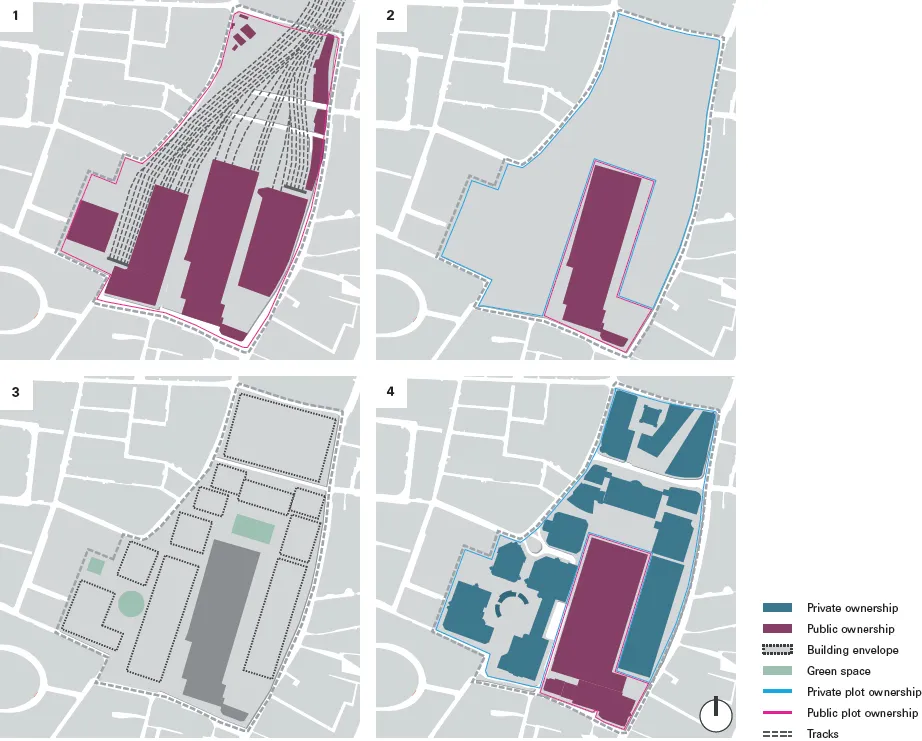

PROJECT ORGANISATION / TEAM STRUCTURE

In 1975 British Rail had commissioned the well-established architectural practice Fitzroy Robinson & Partners for a major redevelopment study of both Broad Street and Liverpool Street Stations. The outcome, which called for the demolition of all historic buildings on the sites, quickly encountered fierce opposition from politicians and conservationists. A public enquiry was held, resulting in the Grade II listing of several parts of Liverpool Street Station. In 1983 an act of Parliament mandated the redevelopment of the station and British Rail announced a consortium of Taylor Woodrow Property Company and Wimpey Property Holdings as developers of the site. However, the controversy continued, essentially based on the proposal’s low viability through the fact that most of the site was still considered backland. British Rail was forced to start afresh, drawing up a shortlist of eight developers to submit new ideas. Due to the success of the brand-new 1 Finsbury Avenue, Rosehaugh Stanhope Developments and their designer Arup Associates were finally appointed in 1985. Their highly profitable proposal transformed the former backland into a first-rate address with significant property values. This enabled the British Rail Property Board to restore parts of the historic Station structure, and to combine it with striking modern features according to the architectural concept of Peter Foggo from Arup Associates.

Unique in the context of this book, but not unusual for infrastructure-related projects, the financial agreement between the public railway company and the private developer secured for British Rail, in addition to a one-off payment, an ongoing financial participation of between 33.3 and 50 per cent in Rosehaugh Stanhope’s development profits. Typical for the English development tradition (see Belgravia case study for a more detailed explanation), the developers did not acquire unlimited freehold of land, but only the right of use for a specific amount of time – a leasehold – after which all land including the built properties is returned to the freeholder. In this particular case, however, the granting of a 999-year lease reduces a financial distinction between free- and leasehold to absurdity, the calculation period being far too long compared with leasehold lengths of usually less than one hundred years (see also Beijing Central Business District case study for comparison).

The actual buildings of Broadgate were erected in record time, and in three major phases. After the original Arup Associates buildings – including 1 Finsbury Avenue and two later buildings to the east on the same road (eventually incorporated in the Broadgate Estate) – followed those around the ice rink on the former Broad Street Station (also by Arup), and finally those surrounding and built over Liverpool Street Station (by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM)). Unlike the latter, the Arup constructions were built on terra firma and therefore on conventional foundations. Standard for these kinds of developments, each building was held by a separate legal structure which was owned by Rosehaugh Stanhope, but with the possibility of being sold into separate ownership. More unusual is the fact that all exterior squares are likewise maintained as separate legal entities, with appropriate legal mechanisms to secure consistent maintenance for the whole Broadgate site through contributions from the directly adjacent buildings. A dedicated company, Broadgate Estates was established at the outset, in order to assure the maintenance of these exterior spaces as well as the individual buildings’ envelopes and the interiors of the multi-tenant buildings, if required.

The role of the public authorities in the construction of Broadgate is fairly small when compared with other European projects featured in this book. Since the abolition of the Greater London Council under Margaret Thatcher’s government in 1986, the planning authority in London has resided solely with the boroughs, and in the case of Broadgate was essentially limited to the approval or disapproval of the respective building permits for each phase of the development. A masterplan existed from the early stages, but it did not have any legal validity as a long-term development framework. As just one example out of many, the Hilmer & Sattler masterplan for the Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, by contrast, was translated into an official and binding document by the city authority (see separate case study). A particularity in terms of planning background and authority is the unique case of the City of London Corporation, which – together with the Borough of Hackney – was the planning authority in charge of the Broadgate development. It is of medieval origins and holds a status that situates it somewhere in between a private ‘Great Estate’ (see Belgravia case study) and another London borough like Westminster, Camden, Kensington and Chelsea or Hackney. The biggest difference compared with these ‘normal’ boroughs is not a specificity of planning procedure, but its very small population of hardly 10,000 residents. The corporation’s main mission is therefore the promotion of the City of London as Europe’s major financial centre and, understandably, not the defence of the few voters’ and residents’ interests in the built environment. This obviously includes and influences the management of building activities, and it can be assumed that it helped align the interests of the landowner, developer and local planning authority enabling the delivery of 12 buildings in only six years.