eBook - ePub

Decoded

The Science Behind Why We Buy

Phil Barden

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Decoded

The Science Behind Why We Buy

Phil Barden

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

In this groundbreaking book Phil Barden reveals what decision science explains about people's purchase behaviour, and specifically demonstrates its value to marketing.

He shares the latest research on the motivations behind consumers' choices and what happens in the human brain as buyers make their decisions. He deciphers the 'secret codes' of products, services and brands to explain why people buy them. And finally he shows how to apply this knowledge in day to day marketing to great effect by dramatically improving key factors such as relevance, differentiation and credibility.

- Shows how the latest insights from the fields of Behavioural Economics, psychology and neuro-economics explain why we buy what we buy

- Offers a pragmatic framework and guidelines for day-to-day marketing practice on how to employ this knowledge for more effective brand management - from strategy to implementation and NPD.

- The first book to apply Daniel Kahneman's Nobel Prize-winning work to marketing and advertising

- Packed with case studies, this is a must-read for marketers, advertising professionals, web designers, R&D managers, industrial designers, graphic designers in fact anyone whose role or interest focuses on the 'why' behind consumer behaviour.

- Foreword by Rory Sutherland, Executive Creative Director and Vice-Chairman, OgilvyOne London and Vice-Chairman, Ogilvy Group UK

- Full colour throughout

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Decoded un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Decoded de Phil Barden en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Negocios y empresa y Negocios en general. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

Decision Science

Understanding the Why of Consumer Behaviour

In marketing our goal is to influence purchase decisions. But what drives those decisions? Decision sciences help to answer this crucial question by uncovering the underlying mechanisms, rules and principles of decision making. These fascinating and valuable insights from science have been expanding rapidly in the past few years. This chapter will go into some of the depths of the latest learnings from decision science, but don’t worry, you don’t need to be a scientist to swim here! We will see what really drives purchasing behaviour, and how to apply these insights to maximize the benefit to marketing. Most importantly, we will introduce a practical framework to harness the learnings in our everyday marketing roles.

Let there be light!

No advert in recent times has won more prizes for creativity or received more public and media attention than Cadbury’s ‘Gorilla’. Brand volumes had been fairly static for years and the brand had suffered the effects of a significant quality problem the previous year. So Cadbury’s objective was to get back into the British public’s ‘hearts and minds’ with a new advert. The agency’s brief was to ‘rediscover the joy’. This resulted in the ‘Gorilla’ advert, in which a gorilla first anticipates and then starts drumming along to the Phil Collins song ‘In the air tonight’. The advert achieved huge amounts of interest and attention, not only from consumers but also from those of us working in brand management. It was a very unusual ad for the category, not least with a gorilla as opposed to the chocolate product taking centre stage. The advert (Figure 1.1) does not contain the usual food or consumption shots either and only at the very end is the packaging shown.

Figure 1.1 The much talked about Cadbury ‘Gorilla’ TV advertisement

Spurred on by the hype and excitement caused by ‘Gorilla’, Cadbury immediately ordered a follow-up campaign. You’d think that nothing could be simpler, yet despite a similar strategy, the same brief, same agency, same director, same campaign objective and media budget, the sequel did not meet client expectations at all. How can this be? Why was ‘Gorilla’ successful in the client’s eyes but the sequel clearly failed? We’ve all experienced similar situations with our own work. Some ads take off and are long-running successes, others fail – and, more often than not, it is hard, if not impossible, to decode the underlying reasons for success and failure.

Another area where the key success principles are often unclear is innovation and new product development. As we all know, the majority of new products launched in any one year fail. Which of us hasn’t experienced cases where our product launches were failures despite market research giving them the green light? Research is carried out, tests are run and, in the end, the predictions are simply wrong. Not only is this costly to the enterprise in terms of wasted resources, it’s also intensely frustrating for us marketers due to the unanswered questions that subsequently plague us: What did we overlook? What went wrong? And what can we learn from this in order to prevent us from simply following a trial-and-error approach? What can we improve in our thinking and process? The uncertainty dangles like the sword of Damocles over the heads of those people responsible and their colleagues, which is not exactly conducive for the next innovation.

The reverse scenario happens, too: an innovation, which might actually have been successful, isn’t even introduced because market research predicted it would fail. To give an example, Baileys liqueur was rejected by consumers but was launched anyway and turned out to be a great success. Likewise, during product testing prior to Red Bull’s introduction, customer comments like ‘yuk’, ‘disgusting’, ‘tastes like medicine’ and ‘I would never drink this’ were commonplace, and yet today Red Bull is available almost everywhere in the world and is hugely successful.

In times of reduced budgets and a growing requirement to justify marketing expenditure, achieving effective branding in our activities is crucial. This is not only a critical factor in our return on investment, it also ensures that we don’t spend money to benefit the competition or, indeed, solely advertise to support the whole category. Our communication should anchor our brands efficiently in the minds of consumers. If ‘branding’ scores are below the required benchmark in a pre-test, how often have we heard (or even made) recommendations such as ‘make the logo bigger’? However, it is unlikely that these kinds of recommendations will fix the problem. When we look at the image in Figure 1.2, what brand is it for?

Figure 1.2 The brand isn’t present and yet we know it

We can immediately recognize it as O2 – even without any direct brand information like the logo. But how do we know? One could argue that the bubbles are a key visual for the brand. This is true, but does this mean that any kind of bubble would activate the O2 brand? Probably not, so what is it that makes it O2? What are the principles that underlie successful branding? While some ads achieve above-average brand recall, for others the brand linkage is very weak – and yet our brand logo is always integrated somehow, so why exactly do these differences occur?

Despite all our efforts, be it working on strategy, communication or market research, the direct path to successful marketing often resembles a stumble through a weakly illuminated black box, and still leaves many questions unanswered.

If these examples ring any bells then they help illustrate that, in order to make progress, we need to better understand how people really decide, and what drives their decisions when it comes to choosing brands and products. The great news is that there is now a systematic approach to human decision making that we can take, one that is both scientifically valid and practical for marketers.

Decision science and economics merge

In a study into the neural bases of decision making, German neuro-economist Professor Peter Kenning and his associates looked at brain scans of people who had been shown photographs of pairs of brands. These photos either included the person’s stated favourite brand or did not. Every time they were shown one of the photographs, each person was told to choose a brand to buy. There were two main findings. First, when the favourite brand was included, the brain areas activated were different to when two non-favourite brands were exposed. When the favourite brand was present, the choice was made instantly and, correspondingly, the brain showed significantly less activity in areas involved in reflective thinking, an effect the scientists named ‘cortical relief’. Instead, brain regions involved in intuitive decision making were activated (in particular the so-called ventro-medial prefrontal cortex in the frontal lobe). In other words, strong brands have a real effect in the brain, and this effect is to enable intuitive and rapid decision making without thinking.

Second, this cortical relief effect occurs only for the respondent’s number one brand – even the brand ranked second does not trigger this intuitive decision making. The scientists call this the ‘first-choice brand effect’. One target we set as marketers is to be in our target consumer’s relevant, or consideration, set. This research indicates that the optimal target is to maximize the number of consumers for whom we are the number one brand – being in the relevant set is not sufficient to enable this intuitive decision making and, of course, no revenue is earned by the brand that was nearly bought!

Intuitive decision making, as a process, is what enables a shopper to stand in front of a shelf and make purchase decisions in milliseconds. But it’s not only about brand and product purchases; it is a characteristic of our everyday lives. It’s even relevant when it comes to numerical logic. In the introduction to his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize, psychologist Daniel Kahneman posed the following simple question:

A baseball bat and a ball cost $1.10 together. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

It’s simple, isn’t it? Nearly everyone to whom this question is posed immediately and intuitively answers that the ball costs 10 cents. This intuitive response was also true of the majority of students at the elite universities of Princeton and Harvard, among whom this exercise was originally conducted. Nearly everyone gives this answer. But it’s incorrect. The ball actually costs only 5 cents (reason: $1.05 for the bat plus $0.05 for the ball equals $1.10). Something in our brain leads most of us, intuitively, to give an incorrect answer to this apparently simple calculation. Instead of doing the mathematics, we resort to our gut feel that, given the $1 price of the bat, 10 cents feels about right as the price for the ball. This intuition is based on the ease of perceiving the split of the 1.10 price tag into two chunks of $1 and 10 cents respectively. Doing the actual calculation is much harder for our brain, and most of us don’t bother because the 10 cent answer feels just right.

Using examples like these, Daniel Kahneman investigates how decisions are influenced through psychological processes. By bridging psychology and economics, Kahneman’s work results in a major opportunity to systematically integrate the psychological world with the world of economics and, in so doing, to exploit the full explanatory power of consumer decision making that the combination of both approaches provides.

Economics and psychology were, for a very long time, two completely separate worlds. Economists start with the basic idea of a rational human being who makes decisions according to objective cost versus utility analyses. Psychologists, meanwhile, emphasize the psychological character of decision making, where the evaluation of value and utility appear irrational, following a kind of psycho-logic. Nowadays, if you do a Google search for ‘neuro-economics’, neuro-marketing’ or ‘behavioural economics’, you will find millions of returns. Among the major drivers of this change were the insights of Daniel Kahneman, the first psychologist to receive the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002.

A science-based framework for marketing

Literally thousands of research papers are being published every year in academic journals such as the Journal of Neuroscience, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Journal of Experimental Psychology and Behaviour and Brain Sciences. There are so many studies and so much data coming from these new fields of decision science, but how can we make sense of them all and integrate the resultant understanding with what we do in marketing?

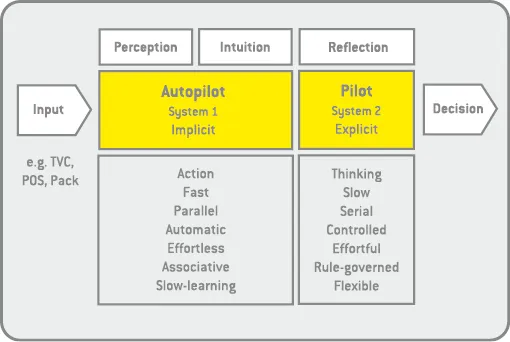

To translate and transfer the insights to our marketing world we need a framework that allows us to systematically apply the most important principles, rules and mechanisms offered by science. The framework we will use to structure this knowledge is also provided by science and is that which Kahneman introduced (see Figure 1.3), and for which he was rewarded with the Nobel Prize. It represents the summary and culmination of the key findings from his life’s work on human decision making. Since the award, Kahneman’s model has been supported by many subsequent studies, including many from the neurosciences, which have also further validated and extended his view of decision making. In his 2011 bestselling book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman gives an up-to-date review of the science underlying his framework.

Figure 1.3 Illustration of Kahneman’s Nobel Prize-winning framework showing the two systems that determine our decisions and behaviour

The core of Kahneman’s framework is the distinction between two systems of mental processes that determine our decisions and behaviour. He calls these two systems ‘System 1’ and ‘System 2’. System 1 integrates perception and intuition. It’s always running – Kahneman says that it ‘never sleeps’. It’s very fast, processes all information in parallel, and is effortless, associative and slow-learning. It is made for fast, automatic, intuitive actions without thinking. Automaticity is crucial because it’s efficient and hence consumes less energy. In times when energy was a scarce resource this efficient way of acting and deciding was key to survival. Reflective thinking requires energy so, in a way, our brain is not made for thinking, but for fast and automated actions. The most highly skilled mental activities are based on System 1, such as cardiologists interpreting an ECG trace, chess masters deciding on the next move, or agency creatives coming up with a new design. In contrast, system 2 is slow, works step by step, takes up a lot of energy because it is effortful, but has the benefit of being flexible. It enables us to make reflective, deliberate decisions. It is made for thinking.

The experiment cited earlier that revealed that brands induce ‘cortical relief’ shows that strong brands are processed in System 1. Indeed, the hallmark of a strong brand is to activate System 1 and circumvent System 2 processing. Weak brands, by contrast, activate System 2, i.e. consumers have to think about the purchase decision.

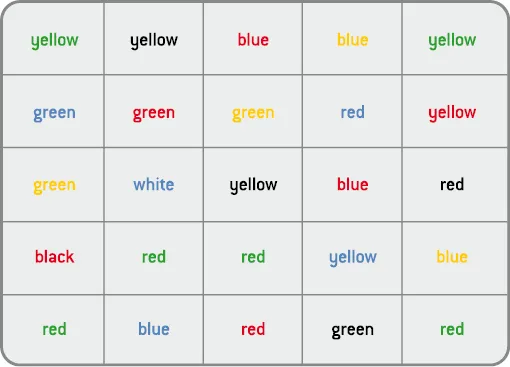

Subjectively we do not usually experience that there are two separate systems at work and, in the end, we make one coherent decision. We notice both systems only when they are in conflict, as in the baseball bat example above. We reflectively understand the calculation but our intuition just tells us something different. Another demonstration of the same principle is shown by the following exercise. Have a look through the table in Figure 1.4 column by column and say out loud as quickly as possible the colours of the words (i.e. you start at the top left corner with ‘green’, ‘black’, ‘red’ . . .).

Figure 1.4 The Stroop test demonstrates the two systems in action

You didn’t find it that easy, did you? At the very least it took you considerable effort and concentration. The meaning of each word can be automatically processed, as can the colour (System 1). However, when word meaning and colour are in conflict, naming the colour takes some time and needs to be done reflectively (System 2). The two pieces of information do not match and this induces a confli...