![]()

1

Haemopoiesis: physiology and pathology

Definition and sites

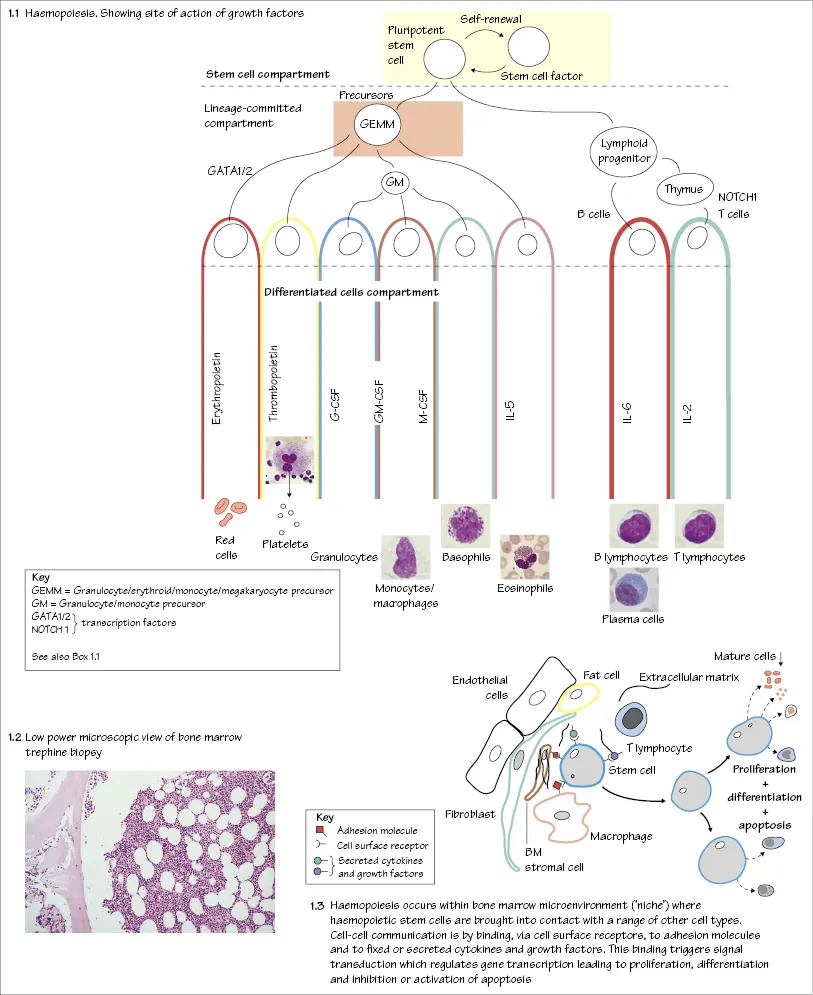

Haemopoiesis is the process whereby blood cells are made (Fig. 1.1). The yolk sac, and later the liver and spleen, are important in fetal life, but after birth normal haemopoiesis is restricted to the bone marrow.

Infants have haemopoietic marrow in all bones, but in adults it is in the central skeleton and proximal ends of long bones (normal fat to haemopoietic tissue ratio of about 50 : 50) (Fig. 1.2). Expansion of haemopoiesis down the long bones may occur in bone marrow malignancy, e.g. in leukaemias, or when there is increased demand, e.g. chronic haemolytic anaemias. The liver and spleen can resume extramedullary haemopoiesis when there is marrow replacement, e.g. in myelofibrosis, or excessive demand, e.g. in severe haemolytic anaemias such as thalassaemia major.

Stem and progenitor cells

Haemopoiesis involves the complex physiological processes of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (programmed cell death). The bone marrow produces more than a million red cells per second in addition to similar numbers of white cells and platelets. This capacity can be increased in response to increased demand. A common primitive stem cell in the marrow has the capacity to self-replicate and to give rise to increasingly specialized or commited progenitor cells which, after many (13–16) cell divisions within the marrow, form the mature cells (red cells, granulocytes, monocytes, platelets and lymphocytes) of the peripheral blood (Fig. 1.1). The earliest recognizable red cell precursor is a pronormoblast and for granulocytes or monocytes, a myeloblast. An early lineage division is between lymphoid and myeloid cells. Stem and progenitor cells cannot be recognized morphologically; they resemble lymphocytes. Progenitor cells can be detected by in vitro assays in which they form colonies (e.g. colony-forming units for granulocytes and monocytes, CFU-GM, or for red cells, BFU-E and CFU-E). Stem and progenitor cells also circulate in the peripheral blood and can be harvested for use in stem cell transplantation.

The stromal cells of the marrow (fibroblasts, endothelial cells, macrophages, fat cells) have adhesion molecules that react with corresponding ligands on the stem cells to maintain their viability and to localize them correctly (Fig. 1.3). With osteoblasts these stromal cells form ‘niches’ in which stem cells reside. The marrow also contains mesenchymal stem cells that can form cartilage, fibrous tissue, bone and endothelial cells.

Growth factors

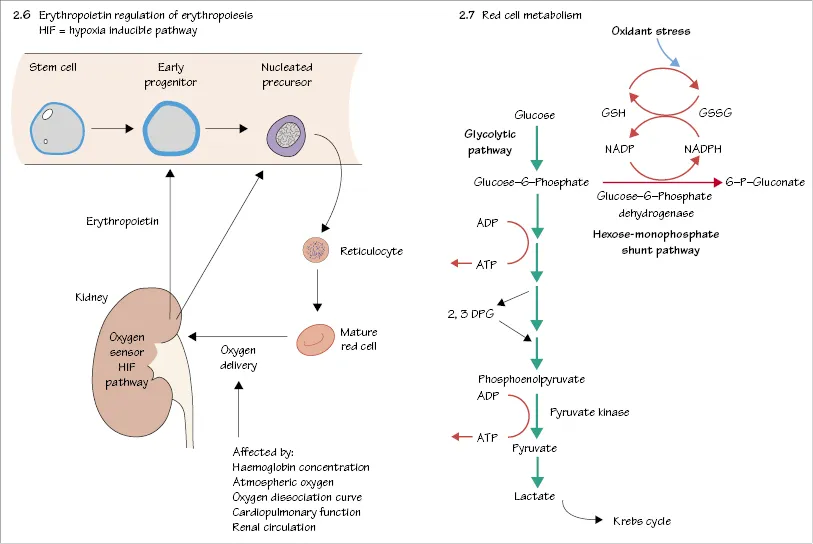

Haemopoiesis is regulated by growth factors (GFs) (Box 1.1) which usually act in synergy. These are glycoproteins produced by stromal cells, T lymphocytes, the liver and, for erythropoietin, the kidney (Fig. 2.6). While some GFs act mainly on primitive cells, others act on later cells already committed to a particular lineage. GFs also affect the function of mature cells. The signal is transmitted to the nucleus by a cascade of phosphorylation reactions (Fig. 1.4). GFs inhibit apoptosis (Fig. 1.5) of their target cells. GFs in clinical use include erythropoietin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and analogues of thrombopoietin.

Box 1.1 Haemopoietic growth factors

Act on stromal cells

- IL-1 (stimulate production of GM-CSF, G-CSF, M-CSF, IL-6)

- TNF

Act on pluripotential cells

Act on early multipotential cells

Act on committed progenitor cells*

- G-CSF

- M-CSF

- IL-5 (eosinophil CSF)

- Erythropoietin

- Thrombopoietin

Transcription factors

These proteins regulate expression of genes e.g. GATA1/2 and NOTCH. They bind to specific DNA sequences and contribute to the assembly of a gene transcription complex at the gene promotor.

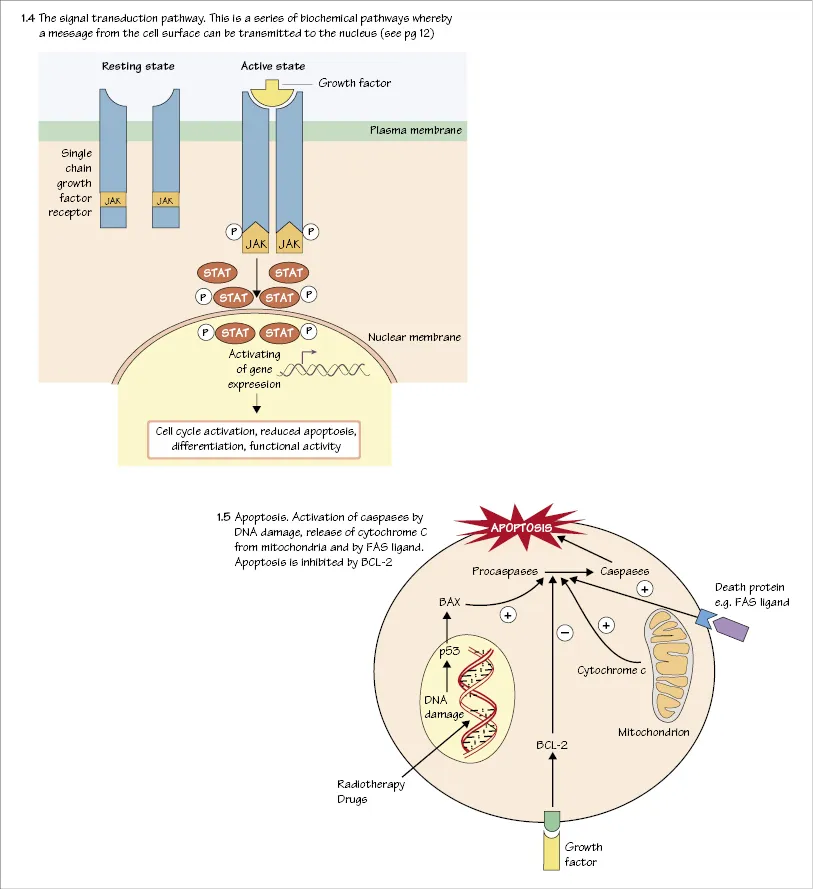

Signal transduction (Fig. 1.4)

The binding of a GF with its surface receptor on the haemopoietic cell activates by phosphorylation, a complex series of biochemical reactions by which the message is transmitted to the nucleus. Figure 1.4 illustrates a typical pathway in which the signal is transmitted to transcription factors in the nucleus by phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT molecules. The transcription factors in turn activate or inhibit gene transcription. The signal may activate pathways that cause the cell to enter cell cycle (replicate), differentiate, maintain viability (inhibition of apoptosis) or increase functional activity (e.g. enhancement of bacterial cell killing by neutrophils). Disturbances of these pathways due to acquired genetic changes, e.g. mutations, deletion or translocation, often involving transcription factors, underlie many of the malignant diseases of the bone marrow such as the acute or chronic leukaemias and lymphomas.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis (programmed cell death) is the process by which most cells in the body die. The individual cell is activated so that intracellular proteins (caspases) kill the cell by an active process. Caspases may be activated by external stimuli as intracellular damage, e.g. to DNA (Fig. 1.5).

Assessment of haemopoiesis

Haemopoiesis can be assessed clinically by performing a full blood count (see Normal values). Bone marrow aspiration also allows assessment of the later stages of maturation of haemopoietic cells (Fig. 7.3; see Chapter 7 for indications). Trephine biopsy (Fig. 1.2) provides a core of bone and bone marrow to show architecture. Reticulocytes (see Chapter 2) are young red cells. Assessment of their numbers can be performed by automated cell counters and will give an indication of the output of young red cells by the bone marrow. As a general rule, the action of GFs increases the number of young cells in response to demand.

![]()

2

Normal blood cells I: red cells

Peripheral blood cells

Normal peripheral blood contains mature cells that do not undergo further division. Their numbers are counted by automatic cell counters which also determine red cell size and haemoglobin content.

Red cells (erythrocytes)

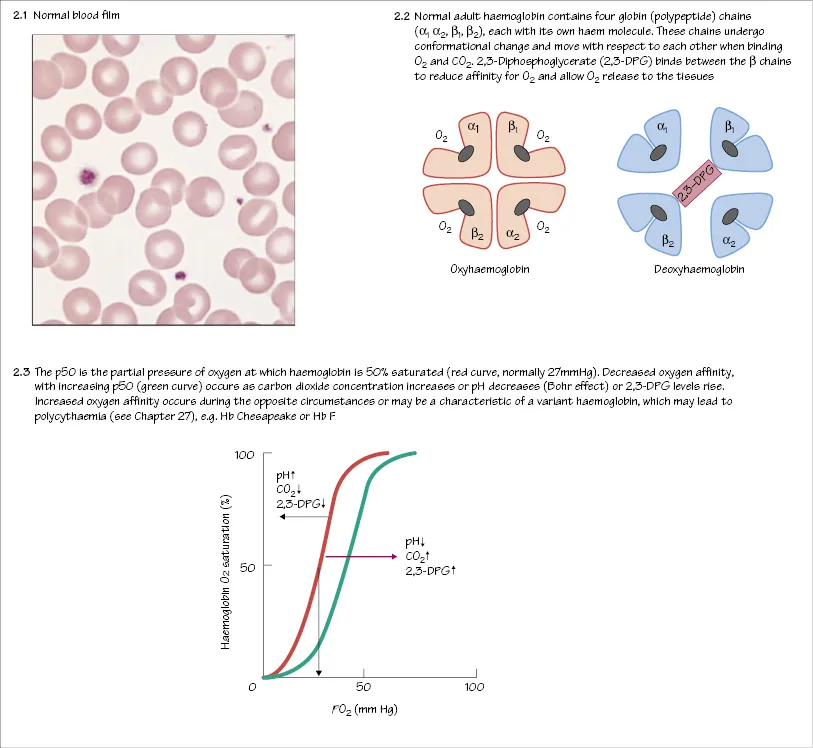

Red cells are the most numerous of the peripheral blood cells (1012/L) (Fig. 2.1). They are among the simplest of cells in vertebrates and are highly specialized for their function, which is to carry oxygen to all parts of the body and to return carbon dioxide to the lungs. Red cells exist only within the circulation – unlike many types of white blood cells they cannot traverse the endothelial membrane. They are larger than the diameter of the capillaries in the microcirculation. This requires them to have a flexible membrane.

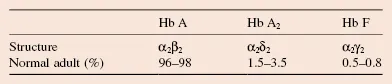

Haemoglobin

Red cells contain haemoglobin which allows them to carry oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Haemoglobin is composed of four polypeptide globin chains each with an iron containing haem molecule (Fig. 2.2). Three types of haemoglobin occur in normal adult blood: haemoglobin A, A2 and F (Table 2.1). The ability of haemoglobin to bind O2 is measured as the haemoglobin–O2 dissociation curve. Raised concentrations of 2,3-DPG, H+ ions or CO2 decrease O2 affinity, allowing more O2 delivery to tissues (Fig. 2.3). Some pathological variant haemoglobins are similar to Hb F in having a higher oxygen affinity than Hb A (Fig. 2.3); this leads, in adults, to a state of relative tissue hypoxia and the body compensates by increasing the number of red cells (secondary polycythaemia, see Chapter 26). In contrast, some pathological variant haemoglobins (e.g. Hb S, the major haemoglobin in sickle cell disease, see Chapter 17) have a lower oxygen affinity than Hb A (Fig. 2.3). This allows individuals to maintain a higher than normal tissue oxygenation for a given haemoglobin concentration.

Table 2.1 Normal haemoglobins

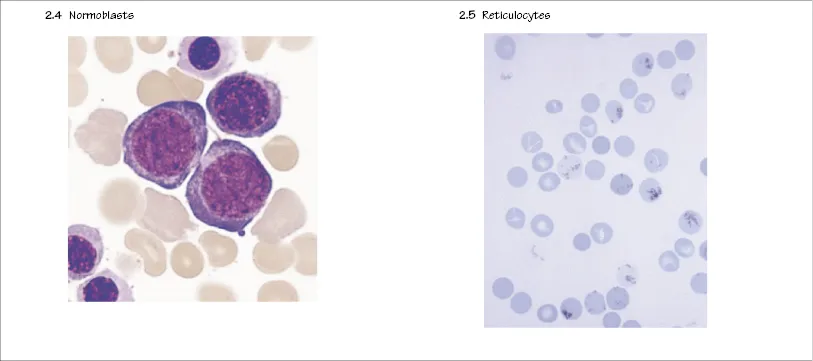

Red cell production

The earliest recognizable red cell precursor is a pronormoblast (Fig. 2.4). This arises from a progenitor cell CFU-E committed to red cell production. The pronormoblast has an open nucleus, a cytoplasm that stains dark blue (because of a high RNA content) with the usual (Romanowsky) stain for bone marrow blood cells. By a series of cell divisions and differentiation (with haemoglobin formation in the cytoplasm), the cells develop through different normoblast stages until they lose their nuclei. Ten to fifteen percent of developing erythroblasts die within the marrow without producing mature red cells. This ‘ineffective erythropoiesis’ is increased and becomes an important cause of reduced haemoglobin concentration (anaemia) in various pathological states, e.g. thalassaemia major...