![]()

Section 1

Understanding a physiologic approach

![]()

Chapter 1

The case for a physiologic approach to birth: An overview

Melissa D. Avery

Childbirth is normal until proven otherwise.

Peggy Vincent

Picture yourself at a neighborhood clinic on a typical weekday. You are conducting a health care visit with a woman as her prenatal care provider; she is 32 weeks pregnant. You ask how she has been feeling—she is fine. Her fundal height is 33 cm, the baby feels vertex, fetal heart tones are 134 beats per minute, a 2-pound weight gain since her last visit. No, she has not experienced any bleeding or headaches, no contractions. Yes, she started prenatal classes this week and the instructor reviewed the signs of early labor. Transition to the hospital. You’re the nurse admitting a woman in labor to the birthing room with the bed centrally located, the fetal monitor in an attractive wood cabinet next to the bed. You ask when her contractions began, the current frequency and duration, and if her baby has been moving. Her membranes are intact, vital signs are normal, fetal heart rate 148. While you turn down the bedcovers, she changes into a hospital gown and asks if water birth is possible; she read about it on a pregnancy website and thought it might be a nice option.

On the face of it, the daily experiences of many maternity care clinicians and the women we care for seem pretty normal, routine, and positive to a degree. We talk about pregnancy as a normal life process, yet women enter our care system where problems are anticipated rather than emphasizing the normalcy of pregnancy. The number and frequency of technological interventions continue to increase while the outcomes of care have worsened, with some recent abatement. Substantial national resources are spent on what is supposed to be a normal process. From the clinic to the hospital, how do we as nurses, midwives, and physicians provide a safe and high-quality experience for the women we care for during pregnancy and birth? How are we helping women plan for and achieve their goals and desires for their birth experiences?

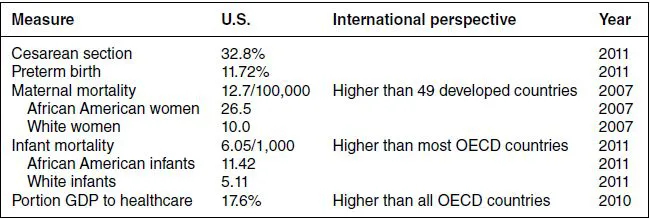

Cesarean section has become the most common operating room procedure in America [1]. The U.S. cesarean section rate is nearly 33%, appearing to at least stabilize in 2010 and 2011 after rising by 60% from 1996 to 2009 [2,3]. The Healthy People 2020 goal is a moderate 10% reduction in cesarean births to low-risk women (term, singleton, vertex) from a baseline of 26.5% in 2007 to 23.9% by 2020, as well as a 10% increase in vaginal births among women with a previous cesarean [4]. At the same time, infant mortality, a measure used worldwide to reflect care to mothers and families, is 6.05 deaths in the first year of life per 1,000 live births [5]. This is higher than all but three member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an organization of primarily developed countries including Europe, the United States, Canada, and others [6]. Infant mortality in the United States has declined from 6.71 per 1,000 live births in 2006 after remaining stable from 2000 to 2005 [7]. An 8% decline in premature births occurred from 12.80% in 2006 to 11.72% in 2011 [3], along with increased efforts at preventing early elective births such as the March of Dimes and the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative [8,9]. Maternal mortality was 12.7 per 100,000 live births in 2007 [10], a number that may be increasing [11], with the U.S. rate behind forty-nine other developed nations in 2010 [12]. (See summary data in Table 1.1.)

Table 1.1 U.S. maternity care data.

Not readily apparent in these statistics are significant racial disparities. For example, infant mortality among African American women was 11.42 per 1,000 live births, 2.2 times greater than the 5.11 for White women [5]. Maternal mortality was approximately 3 times higher for African American women compared to White women [10,11]. These disparities are inexcusable in a country with such vast resources; we must reverse these trends by assuring access to continuous high-quality health care [13]. Returning to a more normal or physiologic approach to maternity care including access to comprehensive continuous care to all women in the United States is one step in that direction.

Spending and doing too much

Nearly 99% of U.S. births occur in hospitals [2], thus “liveborn infant” and “pregnancy and childbirth” are among the most common reasons for hospitalization [1], accounting for nearly a quarter of hospital discharges in 2008, and over $98 billion in hospital charges (amount hospitals bill for a stay). Medicaid payment covers the cost of care for over 40% of pregnancies and births [14]. Of “pregnancy and childbirth” and “liveborn infant” hospitalizations in 2008, $41 billion was paid by Medicaid and $50 billion was paid by private insurers [15]. The United States spent 17.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) on health care in 2010, more than any of the other OECD countries [6]. This phenomenon of doing more in perinatal care without a corresponding improvement in care outcomes was first referred to as the “perinatal paradox” more than 20 years ago [16]. Tremendous resources are allocated to maternal and infant care in the United States and yet our outcomes do not compare well with other developed countries. Although preterm birth has declined in recent years and the cesarean rate may have stabilized, there is much more work to be done.

The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 marked the first success in half a century of legislative attempts to change health care in the United States. When fully implemented, millions more Americans will have health care coverage. An important focus of the ACA is on improving health care and reducing costs by enhancing coordination of care for individuals with chronic conditions, reducing medical errors, reducing hospital-acquired infections, and reducing waste in the system. Improving health care, improving care outcomes including client satisfaction, and providing care at lower cost, often referred to as the triple aim, are not only possible but necessary. In addition to improved access to health care, ACA improvements in care options for women include family planning and breast and cervical cancer screening without co-pays, coverage for maternity and newborn care, home-visiting services during pregnancy and early childhood, restricting insurance companies from charging women higher premiums than men, and enhanced support for breastfeeding mothers [17].

Concerns about the increased use of technology and medical intervention overuse in maternity care have been expressed by clinicians, scientists, educators, and others around the world. Multiple health professions and health-related organizations worldwide have issued statements calling for a more normal or physiologic approach to pregnancy and birth. Concerned with the rising rates of interventions in maternity care in the United Kingdom, the Maternity Care Working Party published a normal birth consensus statement in 2007, supported by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Royal College of Midwives, defining “normal delivery” as spontaneous labor, labor progression, and birth, without the use of interventions such as labor induction, epidural, cesarean section, and forceps. The statement proposes action steps to increase the proportion of normal births in the four UK countries [18]. Other statements, in some cases endorsed by multiple health professions organizations, have called for support of birth as a normal process, reduced intervention, use of best available evidence, and woman-centered care [19–22]. More recently, in the United States, the American Academy of Family Physicians; American Academy of Pediatrics; American College of Nurse-Midwives; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses; and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine endorsed a statement on quality patient care in labor and delivery identifying pregnancy and birth as normal processes requiring little if any intervention in most cases [23]. The authors called for effective communication, shared decision making, teamwork, and quality measurement in the provision of maternity care. Three U.S. midwifery organizations partnered in the development of a statement supporting physiologic birth—defining normal physiologic birth, identifying factors that disrupt and factors influencing normal birth, and proposing a set of actions to promote normal birth [24]. Reflecting the growing concern about the U.S. cesarean section rate, authors of a report summarizing a recent workshop held by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, plus a similar commentary, recommended specific practices and actions for clinicians and health systems to prevent the first cesarean section [25,26]. At least on paper, it seems as if we all agree.

Internationally, a series of normal labor and birth conferences have been held beginning in England in 2002 and most recently in China in 2012 [27]. The conferences highlight current research and best practices in promoting normal birth. In the United States, authors of a key report on evidence-based maternity care have identified induction of labor and cesarean section as overused procedures. Additionally, midwives, family physicians, and prenatal vitamins were described as underused interventions [28]. Following that report, Childbirth Connection, a nonprofit organization focused on improving maternity care, held a multistakeholder meeting focused on just how the quality and value of maternity care could be improved in the United States. The resulting “Blueprint for Action: Steps toward a High-Quality, High-Value Maternity Care System” provides clinicians, payers, educators, and care systems with excellent proposals to improve our care to women [29]. Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns, a federally funded program under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, has provided funding to reduce early elective births and to test new models of enhanced prenatal care to meet the triple aim. The models include enhanced prenatal care in group prenatal settings, in birth centers, and in maternity care homes [30].

In order to improve quality, health systems need to measure and report on the care provided [29,31,32]. Maternity care measures are available for use to improve quality such as the Joint Commission, the National Quality Forum, and the American Medical Association (AMA). The AMA Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement measure set was developed by an interprofessional work group and includes measures related to overuse of certain care practices as well as a measure for spontaneous labor and birth [33]. These quality measure sets are available to health systems, clinicians, and payers to improve care and achieve better care outcomes. In addition to the national measure sets, a tool to examine the optimal processes and outcomes of normal pregnancies among groups of women has been developed and tested. The Optimality Index-US measures what is “optimal” or best possible care processes and outcomes—within a philosophy of aiming for the best outcome using the least number of interventions [34–36]. Higher Optimality scores in one setting over another may reflect an environment that supports a low intervention and physiologic approach to prenatal and labor care. Available as a research tool, clinicians can also use the index to examine institutional care processes and in peer review and other quality improvement processes [35].

Looking for something different

Women have signaled that they are beginning to look for something different, evidenced by the recent increase in out-of-hospital births [37]. After declining since 1990, home births increased by 29% from 2004 to 2009 [38]. In 2010, the increase in both home and free-standing birth center births was large enough to cross the “99% mark,” documenting more than 1% of births occurring outside the hospital [2]. While the absolute number may not seem impressive (47,000 of nearly 4 million), the change is a message that a segment of the U.S. childbearing population is looking for something else. Birth is important to women, often a transformative event that they remember clearly throughout their lives. Many women believe labor and birth should not be interfered with and women understand their right to full information and to accept or refuse specific care processes [39]. Women are asking for specific services in hospitals such as water immersion, aromatherapy, and acupressure as part of the support tools available for labor and birth. Although epidurals remain popular, ...