eBook - ePub

Cultural Criticism

A Primer of Key Concepts

Arthur A, Berger

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 216 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Criticism

A Primer of Key Concepts

Arthur A, Berger

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

In this guide to cultural criticism, Arthur Asa Berger presents complex concepts in jargon-free language, making the book an ideal introductory text. It covers the key theorists, concepts, and subject areas, from literary, sociological and psychoanalytical theories of semiotics and Marxism. Berger brings cultural criticism to life by making these theories relevant to see students' lives. Illustrating his explanations with excerpts from classic works, Berger gives readers a sense of the style of important thinkers and helps place them in context. There is an extensive bibliography which will be an invaluable resource for those who wish to explore the topics in greater depth.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Cultural Criticism un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Cultural Criticism de Arthur A, Berger en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Scienze sociali y Cultura popolare. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

An Introduction to Cultural Criticism

Writing a little book about a big subject is an extremely difficult thing to do. It is much harder than writing a big book about a little subject, which seems to be the standard operating procedure for many writers nowadays. Somehow, over the past 30 years, I have taken on the task—or perhaps it would be a bit more accurate to say that I have ended up with the task—of explaining complicated subjects in clear and relatively simple (but not simplistic, I hope) terms, and have done so in a number of little books on big subjects. It takes a good deal of effort, I might add, to write books on complicated subjects that are accessible and that readers find interesting.

The Mission Impossible Dream

I have this recurring dream. It is 3:00 A.M. and I find myself, somehow, in a deserted building on a college campus. I walk into a large, empty lecture hall, where I see a tape recorder on a table. Beside it is a manila envelope. I walk over to the table and press the button that turns on the tape recorder. This is what I hear:

Your mission, if you accept it, Arthur, is to explain cultural criticism and cultural studies in easy-to-understand terms. You will write an accessible book that deals with many of the important concepts and ideas in literary theory, semiotics, psychoanalytic thought, Marxist thought, and sociological thought for readers who may have little or no background in these areas. We have assembled an international team of experts to help you carry out your mission. Their photographs are found in the sealed envelope you see before you. If you are taken prisoner by the postmodernists, neither your dean, your department chair, nor your editor will accept responsibility for you or aid in obtaining your release. This tape will self-destruct in three seconds.

Three seconds later, the tape goes POOF and burns up. I pick up the envelope and tear it open. In it are photographs of a number of people: Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Ferdinand de Saussure, Mikhail Bakhtin, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and a dozen others. “Good,” I think. “I’ve got an international team of superstar philosophers, psychologists, and cultural theorists to help me!”

Then I wake, in a cold sweat. “Good Lord, what have I gotten myself into?” I ask myself. I then have a breakfast of orange juice, oatmeal with hot milk, yogurt, a caffé latte, and toast. I skim the San Francisco Chronicle and New York Times. Then, with a sigh, I get up from the breakfast table and walk slowly to a room lined with books, where a computer sits on a desk. I turn on the computer and start typing.

Cultural Criticism and Cultural Studies

Cultural criticism is an activity, not a discipline per se, as I interpret things. That is, cultural critics apply the concepts and theories addressed in this book, in varying combinations and permutations, to the elite arts, popular culture, everyday life, and a host of related topics. Cultural criticism is, I suggest, a multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, pandisciplinary, or metadisciplinary undertaking, and cultural critics come from, and use ideas from, a variety of disciplines. Cultural criticism can involve literary and aesthetic theory and criticism, philosophical thought, media analysis, popular cultural criticism, interpretive theories and disciplines (semiotics, psychoanalytic theory, Marxist theory, sociological and anthropological theory, and so on), communication studies, mass media research, and various other means of making sense of contemporary (and not so contemporary) culture and society.

The term cultural studies is not new; in 1971, the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham started publishing a journal, Working Papers in Cultural Studies, which dealt with media, popular culture, subcultures, ideological matters, literature, semiotics, gender-related issues, social movements, everyday life, and a variety of other topics. I regarded the establishment of the journal as very exciting, for it showed that the people at the University of Birmingham were taking popular culture and the media seriously. Unfortunately, the journal did not last very long. It did, however, have a considerable impact, and it provided a kind of umbrella term that covers what scholars from many disciplines now do—what I have described as cultural criticism.

One of the major problems with cultural criticism is that the vocabulary used in criticism, analysis, and interpretation has become incredibly recondite and highly technical. In many cases it is absolutely opaque. When cultural critics communicate with one another in scholarly books and articles, they do so, generally speaking, in a language that tends to be obscure, full of what the layperson would describe as jargon. It is often extremely difficult to understand.

On Technical Language

Shortly before I started writing this book, I had a conversation with a friend about cultural criticism. “Who reads this stuff?” he asked. “It’s just about unintelligible. I would imagine there’s a relatively small number of people who write these crit-speak books and the only people who might want to read them or can understand them are their friends.” It was that comment that led me to write this book. Despite the jargon and technical language found in much cultural criticism, many of the writers and theorists in the field have useful and suggestive ideas and concepts to share that people interested in the media, popular culture, and related concerns should find valuable—if, that is, these writers and their theories and concepts can be understood. I felt that I could help make their ideas more intelligible for some readers. Some French writers, such as Jacques Derrida, communicate in a notoriously obscure fashion, and it has even been suggested that Derrida and others write impenetrable and opaque prose on purpose, so that if their ideas are attacked they can always argue that they have actually been misunderstood.

We must realize that many of the authors discussed in this volume are addressing very complicated matters, issues, ideas, and theories, so there is good reason for a certain amount of complexity in their writing. They come from many different countries, from a variety of disciplines, and are also writing, generally speaking, for people with a considerable amount of education who are interested in their ideas. Often the readers of the important theorists also have considerable background in the subject under discussion. The problem, as I have noted, is that these writers are not accessible to large numbers of people who, I believe, would find their ideas interesting and suggestive and would benefit from knowing about them.

Making Complex Ideas Accessible

In this book I present some of the more important concepts used in cultural criticism and explain them as simply and clearly as I can. In doing so, I hope to offer readers the conceptual background they need to understand and do cultural criticism. This book, remember, is a primer; it is meant to provide readers with an overview of cultural criticism, a sense of what cultural critics do and how they do it. I make it a point to present quotations that show how significant terms are used by various influential thinkers—to expose readers to the styles of a number of major writers and thinkers. It is my intention for this book to be readable and accessible for most readers; however, even though this is a primer, I must confess that in some places the going does get rather difficult.

On Concepts

We should not be put off by unfamiliar concepts, but should learn what they mean and how to use them, for it is through concepts (which, when linked together, form disciplines and subject matters) that we make sense of the world. The term concept comes from the Latin concipere, which means “to conceive.” In the current context, a concept is an idea, theory, hypothesis, or notion that someone who is interested in cultural criticism uses to interpret, understand, make sense of, find meaning in, and see relationships in

- what characters say and do in texts (and what people in real life say and do in their everyday lives);

- data about the world and the role of institutions in the world;

- the behavior of individuals and groups of people;

- the way the human mind, psyche, and body function, and the relationship between the psyche and the body; and

- the role of texts (works of elite and public art) in the development of individuals and the impact of these texts on society and culture.

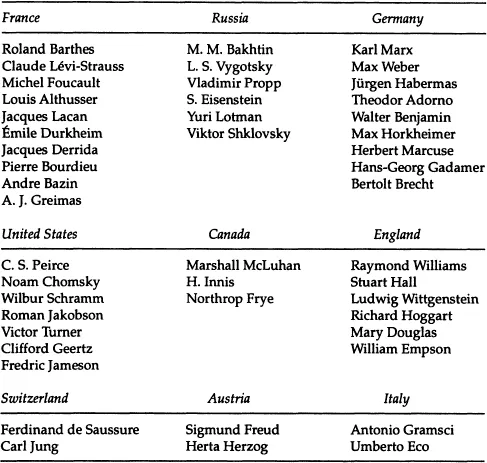

It may be interesting for readers to know where many of the more important thinkers in cultural criticism have come from, so I have constructed Table 1.1—an exercise in what might be called cultural criticism geography. We see that France, Russia, and Germany have produced the lion’s share of cultural critics and theorists, though the table is, admittedly, highly selective—it leaves out many important thinkers. It should be noted that many of the thinkers listed in Table 1.1 are not contemporary either.

TABLE 1.1 The Geography of Cultural Criticism: Countries of Origin of Influential Cultural Studies Theorists (A Selective List)

Thinkers Evolve and Change Their Ideas Over Time

Dealing with the ideas of important theorists is also complicated because we find that theorists often change their ideas over the years (so we are faced with the issue of which of their works should be considered most important). We also find that followers of particular theorists often disagree on how to interpret certain terms, concepts, and theories connected with those theorists. Freud, for example, wrote many books and countless articles and letters that show that he changed his mind about various concepts as his thinking developed. In the same light, there are still arguments about what Marx “really” believed. Was he a humanist and moralist, or did he believe in the need for violent revolution? W. H. Auden once said that the words of the dead are “modified in the guts of the living”—to this we can add that the words of the living are also modified in the guts of the living.

There is, of necessity, a certain amount of reductionism or simplification in this book. It is impossible to deal with difficult and extremely complicated concepts such as deconstruction and postmodernism in just a few pages without leaving a great deal out. It is possible, however, to capture the gist of such theories and give readers a pretty good idea of what they are about. I believe that by using quotations judiciously and explaining concepts in language that is relatively easy to understand, I can enable readers to make sense of cultural criticism.

A Useful Analogy

Let me offer an analogy that might be useful here. Assume that you have never been to Europe and are planning a trip there for a few months and hope to visit five or six countries. You might begin to plan your trip by reading a general travel book on Europe. Once you have read it, you can then turn to books on individual countries (such as France), particular areas in individual countries (such as central France), individual cities (such as Paris), and even particular areas of particular cities (such as Montparnasse) to get more detailed information. But you need to get a good overview and some ideas about the best places to go before you start finding out, in depth, about specific countries, areas, and cities.

Readers who want more information about specific concepts, ideas, issues, topics, theories, or theorists connected with cultural criticism should consult the list of suggested further reading that follows the text. Many of the works found there contain their own substantial bibliographies, which will lead interested readers to even more resources. For example, the literature on postmodernism is enormous. A number of the books on this subject reference articles and other books that will provide anyone interested in this aspect of cultural criticism with a huge reading list, and books on various aspects of postmodernism continue to roll off the presses in increasing numbers. One of the best books on postmodernism, Steven Best and Douglas Kellner’s Postmodern Theory (1991), has a bibliography that lists hundreds of primary and secondary sources.

A Cultural Critic Always Has a Point of View

Cultural critics don’t just criticize out of the blue. They always have some connection to some group or discipline: feminists, Marxists, Freudians, Jungians, conservatives, gays and lesbians, radicals, anarchists, semioticians, sociologists, anthropologists, or some combination of the above. Cultural criticism, then, is always grounded in some perspective on things that the critic (or analyst, if one wishes to avoid the negative connotations of the word critic) believes best explains things.

When looking at the academic or disciplinary identities of individuals doing cultural criticism, in many cases there are no problems. They come from literature departments, sociology departments, philosophy departments, and so on. But in the case of communication schools and departments there is a big problem. One is reminded of the story in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels about the war between Lilliput and Blefescu, which was fought over the correct end from which a person should eat a soft-boiled egg. There is an ongoing dispute about what we should call departments, schools, and colleges devoted to the study of communication. Are they to be called departments, schools, or colleges of communication (without an s) or departments, schools, or colleges of communications (with an s)? Or departments, schools, or colleges or communication, which is what the Annenberg Schools (at the University of Southern California and the University of Pennsylvania) now call themselves (implying, perhaps, that other schools are against communication)? The Annenberg Schools may be correct, but a number of people find it ironic that these schools identify themselves as for co...