![]()

1 Introduction

- Fossils provide information on geological time, evolutionary history, and ancient environments.

- Different organisms have different likelihoods of preservation and the fossil record is generally biased towards shelly, marine organisms.

- The changing shape of the Earth’s surface has had a significant impact on the evolution of living organisms, and the distribution of fossils mirrors the past distribution of continents on the planet.

- Fossil lagerstätten are deposits with exceptionally well-preserved specimens providing an unequaled view of past organisms.

Introduction

The Earth is the only planet we know to support life. Its long history shows that life and the planet it inhabits have a complicated relationship. Free oxygen in the atmosphere, the ozone shield, the movement of carbon into long-term reservoirs in the deep oceans, and the rapid weathering of rocks on the land surface are obvious examples of this relationship.

The evolutionary history of life on Earth points to the development of a series of faunas that occupied the changing surfaces of the land and sea. Through the extraordinary medium of lagerstätten, or sites of exceptional preservation, it is possible to visualize these vanished communities and to restore some of their behaviors and interactions.

In addition, the process of evolution, via Darwinian natural selection, is recorded in the fossil record. Though incomplete and tantalizing in places, fossils are the only direct information source about the nature of our ancestors, and the ancestors of any life on modern Earth.

The study of fossils offers a view of the past at all scales of space and time. From a single moment, for example the single act of making a footprint, to the study of the evolution of tetrapods, or from the study of a single locality to an analysis of the effect of the break-up of Pangea on the evolution of dinosaurs, the fossil record is the primary source of data. Paleontologists build detailed interpretations and analysis from the study of individual fossils; most are invertebrate animals, preserved in great abundance in the shallow marine record.

In this book, we provide an introduction to the methods by which fossils are studied. We discuss the biases that follow from the process of fossilization, and explain how this can be analyzed for a particular fossil locality. We provide an introduction to evolutionary theory, which is the basis for explaining the consistent changes of shape seen in fossils over time.

We describe the major groups of invertebrate fossils that form the bedrock of the discipline, and also of most introductory courses in the subject. We discuss microfossils, plants, and vertebrates, which, while less commonly encountered, are of such importance to understanding life on Earth. Finally, we briefly narrate the evolution of life on Earth as it is currently understood, including episodes of huge diversification and mass extinction. Throughout the text, we discuss the many ways in which fossils contribute to an improved understanding of the Earth’s system, for example through allowing accurate relative dating of rocks, or as proxies for particular environmental settings.

By the end of this book, you should be able to identify the most common fossils, discuss their ecology and life habits based on an analysis of their detailed shape, understand how each group contributes to the wider studies of paleontology and earth systems science, and appreciate their importance at particular points in Earth’s history. You should have a broad understanding of how life has both evolved on Earth and must be factored into any analysis of the evolution of the planet. You can read the book in sequence, or dip into it at will. You will find that some sections follow on from a previous chapter, but in most cases information is presented in self-contained pieces that fall on a couple of facing pages. We have used diagrams and tables wherever possible to summarize information and we have used as few technical terms as possible, to try to lay bare the ways in which fossils matter.

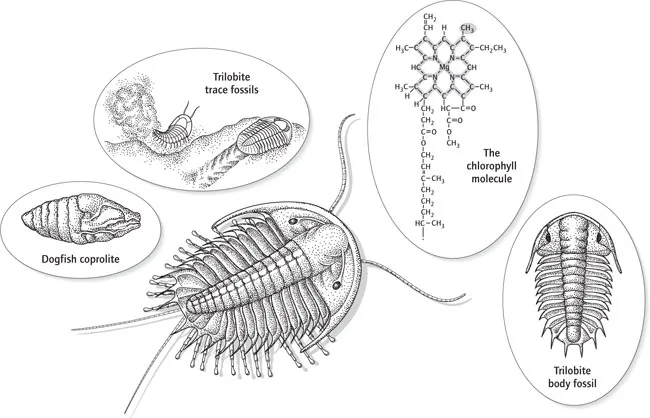

Types of fossils (Fig. 1.1)

Trace fossils

Trace fossils are the preserved impressions of biological activity. They provide indirect evidence for the existence of past life. They are direct indicators of fossil behavior. As trace fossils are usually preserved where they were made, they are very good indicators of past sedimentary environments. Trace fossils made by trilobites have provided an insight into trilobite life habits, in particular walking, feeding, burrowing, and mating behavior.

Coprolites

Coprolites are fossilized animal feces. They may be considered as a form of trace fossil recording the activity of an organism. In some coprolites recognizable parts of plants and animals are preserved, providing information about feeding habits and the interaction of coexisting organisms.

Chemical fossils

When some organisms decompose they leave a characteristic chemical signature. Such chemical traces provide indirect evidence for the existence of past life. For example, when plants decompose their chlorophyll breaks down into distinctive, stable, organic molecules. Such molecules are known from rocks more than 2 billion years old and indicate the presence of very early plants.

Body fossils

Body fossils are the remains of living organisms and are direct evidence of past life. Usually only hard tissues are preserved, for example shells, bones, or carapaces. In particular environmental conditions the soft tissues may fossilize but this is generally a rare occurrence. Most body fossils are the remains of animals that have died, but death is not a prerequisite, since some body fossils represent parts of an animal that were shed during its lifetime. For example, trilobites shed their exoskeleton as they grew and these molts may be preserved in the fossil record.

Fig. 1.1 Types of fossils.

Time and fossils

Geological time can be determined absolutely or relatively. The ages of rocks are estimated numerically using the radioactive elements that are present in minute amounts in particular rocks and minerals. Relative ages of different units of rocks are established using the sequence of rocks and zone fossils. Sediments are deposited in layers according to the principle of superposition, which simply states that in an undisturbed sequence, older rocks are overlain by younger rocks.

Zone fossils are fossils with a known relative age. In order for the zone to be applicable globally, the fossils must be abundant on a worldwide scale. Most organisms with this distribution are pelagic – that is they live in the open sea. The preservation potential of the organism must also be high – that is they should have some hard tissues, which are readily preserved.

Stratigraphy

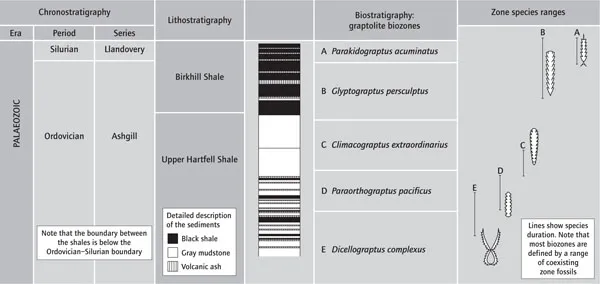

The study of sequences of rocks is called stratigraphy. There are three main aspects to this study: chronostratigraphy, lithostratigraphy, and biostratigraphy (Fig. 1.2).

Chronostratigraphy establishes the age of rock sequences and their time relations. Type sections are often established. These are the most complete and representative sequences of rocks corresponding with a particular time interval. For example, outcrops along Wenlock Edge in Shropshire, UK, form the type section for the Wenlock Series of the Silurian.

A point in a sequence is chosen for a boundary between one geological time interval and the next. It represents an instant in geological time and also corresponds with the first appearance of distinctive zone fossils. Relative timescales can then be established with reference to this precise point. These points are called “golden spikes”.

The differentiation of rocks into units, usually called formations, with similar physical characteristics is termed lithostratigraphy. Units are described with reference to a type section in a type area that can be mapped, irrespective of thickness, across a wide geographic area.

In biostratigraphy, intervals of geological time represented by layers of rock are characterized by distinct fossil taxa and fossil communities. For example, the dominant fossils in Palaeozoic rocks are brachiopods, trilobites, and graptolites.

Fig. 1.2 Stratigraphic description of the sequence of rocks that crosses the Ordovician–Silurian boundary at Dobb’s Linn, Southern Uplands, Scotland. Geological time is split into different zones depending on the method of analysis. Chronostratigraphy divides the section into two periods. Lithostratigraphic analysis divides the sequence into two shales. Biostratigraphy, as determined by the zone fossils, gives a more detailed division of relative age within the sequence.

Life and the evolution of continents

Life exists on a physically changing world, and these changes have both controlled the evolution of organisms and been recorded by their fossil record. Evolution operates rapidly on small populations, and so when a group of organisms becomes isolated through changes in the landscape around them, they quickly evolve to become different to their parent population. Organisms migrate across land bridges or along new seaways, as areas that were once isolated become accessible to one another. The migration of marsupial mammals such as possums into North America over the last 2 million years is a good example of this process. The analysis of the past distributions of organisms is known as paleobiogeography.

Plate tectonics drive changes to the map of the world

The continents and oceans change shape all the time, as crust is generated and modified by the forces of plate tectonics. New oceanic crust is formed at mid-ocean ridges where the mantle decompresses and melts, and as a consequence the oceans grow wider. Crust is consumed at destructive plate boundaries, where dense rock crust sinks back into the mantle. By this process oceans can become smaller or disappear altogether. Continental crust is increased in volume by the addition of island arc remnants and the sediments of the ocean floor. Continental collision joins these fragments together to form large masses, until the formation of new oceans pulls them apart.

The narrative of this evolving world map is well known for the last 200 million yea...