eBook - ePub

Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Adaptation and Learning

Steven R. Lindsay

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Adaptation and Learning

Steven R. Lindsay

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Twenty-five years of study and experience went into the making of this one-of-a-kind reference. Veterinarians, animal scientists, dog owners, trainers, consultants, and counsellors will find this book a benchmark reference and handbook concerning positive, humane management and control of dogs.

Reflecting the author's extensive work with dogs, this book promises thorough explanations of topics, and proven behavioural strategies that have been designed, tested, and used by the author. More than 50 figures and tables illustrate this unique and significant contribution to dog behaviour, training, and learning.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Adaptation and Learning un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Adaptation and Learning de Steven R. Lindsay en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medicina y Medicina veterinaria. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

Origins and Domestication

For thousands of years man has been virtually, though unconsciously, performing what evolutionists may regard as a gigantic experiment upon the potency of individual experience accumulated by heredity; and now there stands before us this most wonderful monument of his labours—the culmination of his experiment in the transformed psychology of the dog.

GEORGE ROMANES, Animal Intelligence (1888)

Archeological Record

Domestication: Processes and Definitions

Interspecific Cooperation: Mutualism

Terms and Definitions: Wild, Domestic, and Feral

The Dingo: A Prototypical Dog

The Carolina Dog: An Indigenous Dog?

Biological and Behavioral Evidence

Biological Evidence

Behavioral Evidence

Effects of Domestication

Morphological Effects of Domestication

Behavioral Effects of Domestication

Paedomorphosis

The Silver Fox: A Possible Model of Domestication

Selective Breeding, the Dog Fancy, and the Future

Origins of Selective Breeding

Prospects for the Future

References

UNDERSTANDING THE dog’s behavior and appreciating its unique status as “man’s best friend” is not possible without studying its evolution and domestication. From ancient times onward, numerous species have undergone pronounced biological and behavioral changes as the result of domestication. The purposes guiding these efforts are as diverse as the species involved. Utilitarian interests such as the procurement of food, security, and other valuable resources or services derived from the animal were surely important incentives, but utilitarian motives alone are not enough to explain the whole picture, especially when considering the domestication of the dog.

Many theories have been advanced to explain how the progenitor of the dog was originally tamed and brought under the yoke of captivity and domestication. These theories often include colorful portraits of primitive life, motives, and purposes that rely on a number of questionable and unprovable assumptions about prehistoric existence (Morey, 1994). For example, one popular view suggests that humans may possess an ageless and universal (innate?) urge to keep animals as pets. Although this theory has some attractive features, it is difficult to defend scientifically. Certainly, dogs share an intimate place in Western society and are often treated with affectionate care in many modern primitive cultures as well (Serpell, 1986/1996); nonetheless, one cannot exclude the possibility that this so-called “affectionate” motive is a rather late cultural development. Further, although it is true that keeping pets as attachment objects is common around the world today, one cannot jump from this observation to the conclusion that a similar set of motives guided ancient people to capture and domesticate wild animals. Attitudes about animals and, in particular, dogs appear to be guided by beliefs and customs that are to a considerable extent conditioned and dependent on cultural, economic, and geographical circumstances (see Chapter 10).

Undoubtedly, a dog’s life during the early stages of domestication was very different than it is today. Over the centuries, the dog’s functions have evolved and changed, sometimes dramatically, depending on the assertion or absence of relevant cultural and survival pressures. In times of scarcity and need, the defining motive for keeping dogs was probably dominated by utilitarian interests; whereas, during times of abundance and well-being, dogs could be readily transformed into convenient objects for affection, comfort, or entertainment.

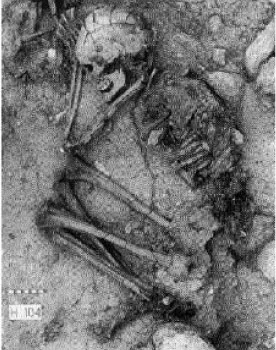

ARCHEOLOGICAL RECORD

Despite the difficulties, discovering when and how this enduring relationship first appeared are questions of tremendous scientific interest and importance. Authorities differ with respect to the exact historical moment or time frame, but many prehistoric sites show that a close association between humans and dogs has existed continuously for many thousands of years. Although a loose symbiotic mutualism probably existed long beforehand, the earliest archeological evidence of a “true” domestic dog is dated to 14,000 years before the present (BP). The artifact (a mandible) was unearthed from a Paleolithic grave site at Oberkassel in Germany (Nobis, 1979, in Clutton-Brock and Jewell, 1993). Protsch and Berger (1973) have collected and carbon dated canine skeletal remains taken at various sites around the world, showing great antiquity and geographical dispersion: Star Carr (Yorkshire, England), 9500 BP; Argissa-Magula (Thessaly), 9000 BP; Hacilar (Turkey), 9000 BP; Sarab (Iran), 8900 BP; and Jericho, 8800 BP. One of the most famous of these archeological finds is a Natufian skeleton of an old human (sex unknown) and a puppy buried together some 12,000 years ago at Ein Mallaha in Israel (Davis and Valla, 1978). The human’s hand is positioned over the chest of the 4- or 5-month-old puppy (Fig. 1.1). One is moved by the ostensible intimacy of the two species buried together, and even tempted to ascribe a feeling of “tenderness” to the embrace binding the person and puppy together over the centuries.

The earliest remains of a domestic dog in North America were found at the Jaguar Cave site in the Beaverhead Mountains of Idaho. These bones had been previously dated from 10,400 to 11,500 BP, but radiocarbon dating of some of the artifacts revealed that they are “intrusions” of a much more recent origin, with a probable age not exceeding 3000 years (Clutton-Brock and Jewell, 1993).

DOMESTICATION: PROCESSES AND DEFINITIONS

Robert Wayne and his associates at UCLA have performed a molecular genetic analysis of the evolution of dogs and wolves, suggesting that efforts to domesticate dogs may have taken place much earlier than indicated by the archeological record, putting the dog’s origins back 100,000 years or more (Vila et al., 1997). The researchers argue that these more ancient efforts to domesticate dogs may have occurred without producing significant morphological change in the protodog, thus explaining the absence of dog skeletal artifacts appearing before 14,000 years ago:

FIG. 1.1. A Natufian burial site at Ein Mallaha in northern Israel shows a human skeleton in what appears to be an “eternal embrace” with the skeletal remains of a puppy located in the upper right-hand corner. From Davis and Valla (1978), reprinted with permission.

To explain the discrepancy in dates, we hypothesize that early domestic dogs may not have been morphologically distinct from their wild relatives. Conceivably, the change around 10,000 to 15,000 years ago from nomadic hunter-gather societies to more sedentary agricultural population centers may have imposed new selective regimes on dogs that resulted in marked phenotypic divergence from wild wolves. (1997:1689)

Although no physical evidence of domestic dogs living with humans before 15,000 years ago exists, skeletal remains of wolves have been found in association with hominid encampments in China (the Zhoukoudian site) from 200,000 to 500,000 years ago (Olsen, 1985).

Although contested in the past, the biological ancestry of the dog is now certain. On the basis of both genetic and behavioral studies the dog is a domestic wolf. However, considerable debate still surrounds the identity of the closest relative among wolf subspecies. Zeuner (1963) has argued that the most likely lupine progenitor is Canis lupus pallipes (the Indian wolf), a small Eastern variety. He bases this assumption on both behavioral and morphological considerations. The smaller Indian wolf would have been less of a threat to human encampments and would have been more readily tolerated than the larger and more aggressive northern varieties.

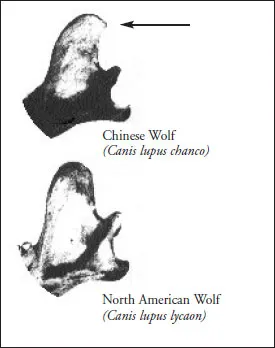

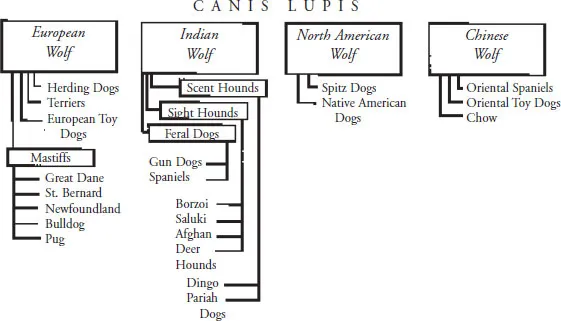

Olsen and Olsen (1977) have selected the Chinese wolf (Canis lupus chanco) as the most likely canid progenitor. They base their choice on this wolf’s small size and mandible morphology, noting that the apex of the coronoid process (the uppermost part of the jaw) turns back in both the Chinese wolf and the domestic dog but not in the jaw bone of other wolf species (Fig. 1.2). Clutton-Brock (1984) has identified Canis lupus arabs (a western Asiatic wolf) and the European wolf as the most likely ancestors of most modern European breeds, with Canis lupus lupus having a greater representation in the genome of Arctic and European spitz-type breeds. It is conceivable that the proliferation of domestic dogs has been genetically influenced by several wolf subspecies at different times and places, or owes its genetic past to a wolf species that is no longer existent (Fig. 1.3).

FIG. 1.2. Note how the apex of the coronoid process (see arrow) tends to turn back. This feature is not apparent in other subspecies of wolves, coyotes, or jackals. It is a common anatomical feature found in dogs, however, suggesting that the Chinese wolf may have played an important role in the ancient domestication of the dog. From Olsen and Olsen (1977), The Chinese wolf, ancestor of New World dogs, Science 197: 533–535, reprinted with permission.

Interspecific Cooperation: Mutualism

By the end of the last glacial period, early humans’ migratory activities overlapped the hunting range of competing predators, especially wolves. As nomadic people came into contact with wolves, some members of the wolf population may have been confident enough to follow closely behind these migrant hunting and gathering groups. By staying nearby, the ever-opportunistic wolves could have easily tracked animals wounded by hunters, thus securing an easy meal for themselves at least until the advancing hunting party arrived at the scene. Also, by retreating and lingering at a safe distance, wolves could scavenge on the slaughtered remains left behind (Zeuner, 1963). Juliet Clutton-Brock (1984, 1996) has speculated that such a hunting partnership may have played an important role in the development and spread of the bow and arrow as a hunting tool during the Mesolithic period, arguing that wolves or protodogs may have provided a significant advantage to early hunters by tracking and subduing large animals wounded by arrows fitted with sharp stone heads called microliths. Besides forming an effective hunting partnership, wolf-pack territories may have formed around human camps, thus providing a natural protective shield against the threat of predation by other less friendly wolves and competing human groups. Possibly, from this mutually beneficial situation, an ecological niche was formed from which the protodog underwent novel morphological and genetic changes gradually leading to domestic dogs.

FIG. 1.3. Various subspecies of the wolf are believed to have contributed to the genome of the domestic dog. According to one theory, the dog was independently domesticated in various parts of the world, with no single site of origin. Although grouped as though from discrete origins, the breeds included here have probably undergone considerable crossbreeding over their long history of development. After Clutton-Brock and Jewell (1993).

Close social contact of this kind requires that the animal in question possess a high fear threshold and a reduced tendency to flee, essential behavioral characteristics of domestication (Hediger, 1955/1968). Scientific evidence for a genetically divergent distribution of temperament traits based on relative tameness and confidence among canids has been demonstrated in the fox (Belyaev, 1979). Among farm-bred foxes, a small percentage exhibit a reduced tendency to act fearfully or aggressively in the presence of people. By breeding these less fearful individuals together over several generations, Belyaev has developed a strain of tame, human-friendly foxes (see below). Although a similar genetic basis for social tolerance has not been demonstrated in wolves, it is reasonable to assume that a certain percentage of the Pleistocene wolf population was probably less fearful and aggressive toward humans than average wolves. The adaptive value of behavioral polymorphism in wolves and its relevance to domestication have been discussed in detail by Fox (1971) and by Scott, the latter writing,

As a dominant predator the wolf is protected from certain kinds of selection pressure, thus permitting the survival of individuals with a considerable variation from the mean. As a highly social species, wolves should be subject to selection favoring variation useful in cooperative enterprises, as a greater degree of variation permits a greater degree of division of labor. For example, a wolf pack might benefit both by the presence of individuals that were highly timid and reacted to danger quickly and effectively, and also by the presence of other more stolid individuals who did not run away but stayed to investigate the perhaps nonexistent danger. (1967:257)

Similarly, Young and Goldman reported that “wolves held in captivity have shown that in each litter there are two or three whelps that show tameness early; the remainder are absolutely intractable and often die if one attempts to train them” (1944/1964:208–209). This prosocial population would have displayed a greater tolerance for human contact or may have even been “preadapted” for domestication—especially if they were not being actively hunted or persecuted.

Mutual tolerance offered many benefits for both species. Early people who tolerated scavenging and the proximate presence of dogs enjoyed a hygienic benefit (resulting in the control of garbage and pestilence) and a protected perimeter of barking dogs, providing valuable early warning of approaching enemies. After a propitious length of time, perhaps hundreds or thousands of years, such loose symbiotic contact may have resulted in the development of a specialized ecological niche in which the most tame individual wolves began to breed in close association with people. This transitional step would have taken place gradually, requiring little or no purposeful intervention on the part of early humans. Such a pattern of scavenging around human encampments by feral and semiferal dogs is evident in many parts of the world today (Fiennes and Fiennes, 1968). Even in large American cities, semiferal dogs satisfy the majority of their nutritional needs by scavenging (Fox, 1971; Beck, 1973). Alan Beck (1973) has observed that stray dogs satisfy most of their nutritional needs by raiding garbage cans and relying on handouts when garbage is not available. Handouts may have been an important source of food for early dogs as well. Domestic dogs exhibit a unique proclivity and skill for food begging—a behavioral attribute that would have been very useful for underfed primitive canines depending on human generosity for their survival. As the result of a growing familiarity between genetically “tame” scavengers and begging dogs, early people had many opportunities for close interaction, thereby making other social exchanges possible, including the adoption of pups.

John P. Scott (1968) has imagined that a primitive mother, having lost her own child and enduring the discomfort of lactation, may have saved a wolf puppy from the camp soup pot by adopting and nursing it as her own. If, in addition, the wolf happened to be a female, it might have chosen the camp as a suitable place to give birth, resulting in a new generation of even closer interaction and social affiliation. Although such a scenario cannot be proven, it is statistically possible, even plausible. Many examples of the suckling of domestic animals by women have been found among existing tribal cultures (e.g., the Papuan of New Guinea).

Although primitive humans’ intentions and purposes for keeping dogs in close proximity are not known, a certain degree of social tolerance and mutual acceptance was clearly present in both species. In addition to various utilitarian or symbiotic benefits, early interaction between humans and dogs surely depended on a high degree of respectful deference shown by early canids toward humans. Dogs exhibiting threatening tendencies would have been quickly expelled or killed, and eliminated from the gene pool early in the domestication process. Those animals exhibiting submission behaviors and social subordination—that is, a readiness to respond to human directives—would have been more likely to survive and to reproduce under the protection of domestic conditions. Early domestic dogs that also exhibited a high degree of affection toward their captors would have been brought into even closer intimacy, enjoying added protection, better food, and other survival advantages not extended to less affectionate counterparts. As time went on, various specialized functions could have been elaborated out of this basic foundation, including all the familiar roles served by the dog today—for example, alarm barking and protection, hunting activities, herding, draft work, and companionship. Undoubtedly, at some point in the natural history of humans and dogs, interspecies tolerance and cooperative interaction became mutually advantageous, thus forging the foundation for a lasting relationship.

Terms and Definitions: Wild, Domestic, and Feral

Reports following a recent fatal wolf-dog attack exemplify some of the confused ways in which terms like domestic, wild, and tame are used. The victim, a 39-year-old mother of two, was mauled and killed as her children looked on near their Colorado home. Several authorities were asked to comment on the unusual attack. It was the first documented case in which a wolf hybrid had killed an adult person. A police detective investigating the incident said, “They [wolf hybrids] may be domesticated, but they’re still wild animals subject to unpredictable behavior.” Another authority, speaking for a local Humane Society, commented, “Animals like that are not tame. You can pet them but they are wild.” The words tamed and domesticated are used here interchangeably, as though they mean about the same thing, roughly synonyms for pet. But this habit of usage is misleading. Taming is a necessary prerequisite for domestication, but taming alone is not sufficient. Many wild animals can be readily “tamed” by patient handling and socialization, but they cannot be classified as domestic animals until they have also undergone extensive behavioral and biological change resulting from selective breeding over the course of many generations. Such breeding is designed (consciously or unconsciously) to enhance various behavioral and physical characteristics conducive to domestic harmony and utility.

The words wild and feral are also frequently used interchangeably in popular discussions. The feral dog is not simply wild, but is a previously domesticated animal that has been released or has escaped back into nature to reproduce and fend for itself. As is discussed below, dingoes exemplify many characteristic features of feral dogs, having evolved from early Asiatic dogs that escaped domestic captivity on reaching Australia several millennia ago. Since that time, dingoes have reverted to a feral existence with only temporary symbiotic affiliations with humans. Dingoes have existed under such conditions of quasi domestication for many generations without actually returning to a true domestic state.

The Dingo: A Prototypical Dog

An excellent source of ethnographic evidence outlining the general course of early domestication can be found in the enduring relationship between the Aborigines of Australia and dingoes. This symbiotic dyad provides a valuable anthropological picture of what life between primitive humans and early canids may have been like during the earliest incipient stages of domestication. In most details, dingoes differ only slightly from Asian wolves (Canis lupus pallipes), except for modest behavioral and morphological changes associated with quasi domestication—for example, variable tail carriage (sometimes carried in the sickle-like form of dogs), some evidence of piebald marking (especially on the feet and chest), and o...