eBook - ePub

Psychology at the Movies

Skip Dine Young

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Psychology at the Movies

Skip Dine Young

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Psychology at the Movies explores the insights to be gained by applying various psychological lenses to popular films including cinematic depictions of human behavior, the psychology of filmmakers, and the impact of viewing movies.

- Uses the widest range of psychological approaches to explore movies, the people who make them, and the people who watch them

- Written in an accessible style with vivid examples from a diverse group of popular films, such as The Silence of the Lambs, The Wizard of Oz, Star Wars, Taxi Driver, Good Will Hunting, and A Beautiful Mind

- Brings together psychology, film studies, mass communication, and cultural studies to provide an interdisciplinary perspective

- Features an extensive bibliography for further exploration of various research fields

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Psychology at the Movies un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Psychology at the Movies de Skip Dine Young en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Psychology y Social Psychology. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Chapter 1

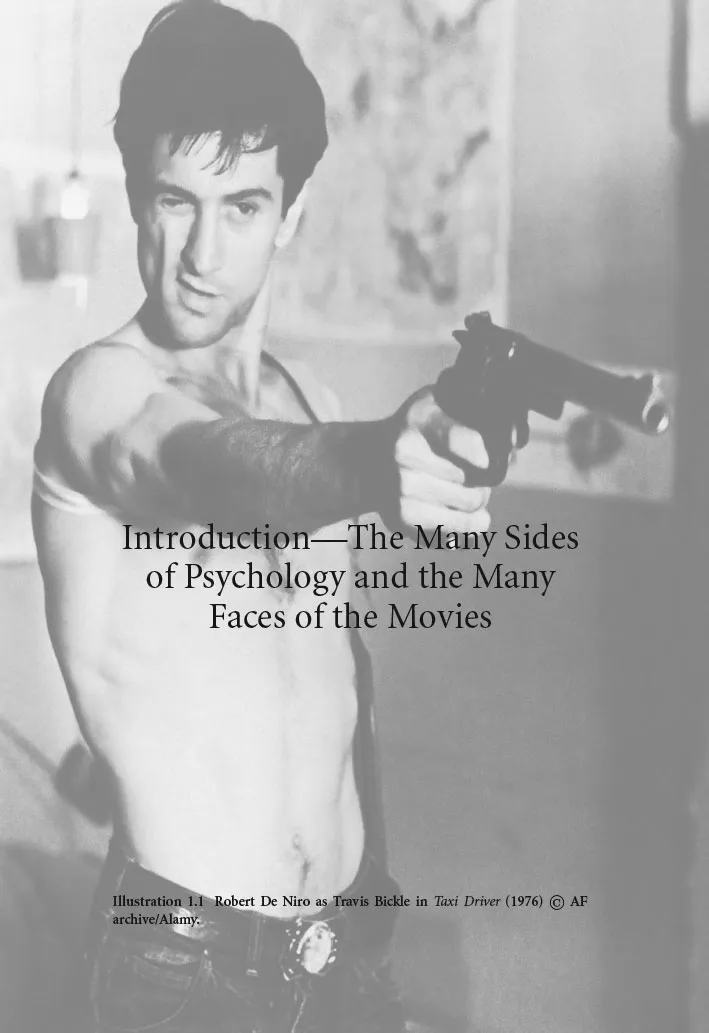

Introduction—The Many Sides of Psychology and the Many Faces of the Movies

Like all art, movies are saturated with the human mind—they are created by humans, they depict human action, and they are viewed by a human audience. Movies are a particularly vivid art form, making use of striking moving images and vibrant sounds to connect filmmakers to the audience through celluloid and the senses.

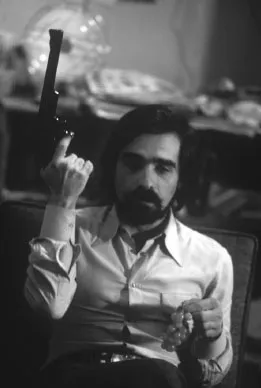

Illustration 1.2 Director Martin Scorsese holds a gun on the set of Taxi Driver © Steve Schapiro/Corbis.

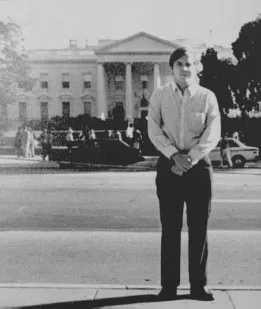

Illustration 1.3 John Hinckley Jr, who attempted to assassinate Ronald Reagan in 1981, poses in front of the White House. © Bettmann/Corbis.

Consider the following story1: Martin Scorsese was born in Flushing, New York in 1942 and grew up in the tough Little Italy section of lower Manhattan. Because of an asthmatic condition he could not play like the other children and spent much his time indoors watching movies, where he was partially protected from the mean streets of New York City, yet felt lonely and isolated. He was deeply immersed in Catholicism and briefly attended a seminary before enrolling in NYU's film school.

By the mid-70s, Scorsese was one of the young, ambitious directors (along with Arthur Penn, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg and others) who were revolutionizing Hollywood. In 1976, he made Taxi Driver about an emotionally unstable cabbie, Travis Bickle, who is trapped by the haunted streets of New York City. Actor Robert De Niro starred in the film and invested Travis's intrapsychic struggles with a terrifying realism.

Taxi Driver was a tour-de-force of raw language, disturbing imagery, and innovative cinematic techniques. In one famous sequence, an elaborate, slow-motion overhead tracking shot surveys the carnage that has resulted from Travis's convoluted attempt to rescue a child prostitute (Jodie Foster). That scene in particular was considered so violent that the Motion Picture Association of America insisted that Scorsese alter the hue of the blood in order to avoid an X rating.

Despite its less than commercial subject matter, Taxi Driver was highly successful and audiences lined up. Reactions among audience members were polarized. Some viewers proclaimed it to be not only technically brilliant but also a cathartic descent into the scarred psyche of an individual character and of America itself. Other viewers found the film to be exploitative and morally misguided. A scene in which Travis, shirtless but outfitted with multiple guns and holsters, looks into the mirror and asks threateningly, “You talkin' to me?” became a part of the common lexicon.

In 1981, one viewer, John Hinckley, Jr, watched the movie 15 times in a retro theater. He was inspired to assassinate President Reagan in order to gain the attention of Jodie Foster with whom Hinckley was romantically obsessed. The assassination failed, but Reagan was shot and several people were seriously wounded, including Reagan's Press Secretary, James Brady, who was paralyzed for life. Hinckley was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and found not guilty by reason of insanity. The incident became part of the cultural debate on the insanity defense, gun control, and the role of media in society.

Over 30 years later, Taxi Driver is still used frequently by pundits and college professors to make points about all manner of things—the cultural zeitgeist of the 1970s; the distortion in media representations; the nature of paranoid thinking; and so on.

Where is the psychology in this story? Obviously, it is everywhere. Scorsese's personal background in a difficult social environment becomes melded with his individual talents and obsessions. These themes of sin, hardship, aggression and redemption appear in films like Taxi Driver, not only in the stories but in the choice of camera angles and color schemes. Aware that art has a relationship to the world outside of the theater, some viewers laud the film for its insightful portrayal of insanity and cultural rot while others find the film disturbing and worry about the message it sends. One psychotic viewer takes the movie as a usable model for assassinating the president. One can easily imagine an entire book on The Psychology of Taxi Driver.

Perhaps a more revealing question is: What is not psychological about this story? There are elements that could be divorced from the realm of psychology—perhaps the technical use of tracking shots or the historical aspects of America in the 1970s. But these distinctions break down if you think about them too much. After all, a camera shot forms the basis for the audience's perceptual experience. And the history of the 1970s is embodied in characters like Travis, artists like Scorsese, and audience members like Hinckley. Once you start looking for it, you can't escape psychology in the movies. There may be ways of talking about movies without highlighting psychological elements, but as a psychologist, I am not sure why anybody would want to.

Goals of Psychology at the Movies

The basic premise of this book is that all movies are psychologically alive, exploding with human drama. This drama has been looked at from many different angles. It is significant that both laboratory psychology and clinical psychoanalysis emerged at almost the same historical point as motion pictures—the end of the nineteenth century.2 The cultural impact of both psychology and film over that next century-plus has obviously been enormous. All along this historical path, there have been many occasions when psychologists have looked at movies as well as many times when movies have looked at psychologists. This book creates a snapshot of the fascinating interweaving between psychology and the movies.

There is no way to even summarize all of the work that has been done on the psychology of movies in one book. The body of available studies, analyses, and commentaries is truly vast—worthy not of a single book but of a library. One prominent early psychologist (and still the psychologist with the best name), Hugo Munsterberg, wrote a book, The Photoplay: A Psychological Study in 1916, and the scholarship has been expanding for a century. The present book can be thought of as a kind of directory for the mythical “International Library of Psychology and Film,” identifying different sections of the library and calling attention to some of the most interesting works.

The scope of fields I cover is far-reaching. As far as I am aware, no other book has attempted to bring so many diverse approaches together under one cover. It considers everything from Freudian psychoanalysis of Hitchcock films to the uncanny popularity of certain movies to children's film-inspired aggression toward a Bobo doll. As the research on film has become more abundant, it has also become more fractured; most recent books addressing issues related to psychology and film are likely to cover only one or two of the chapters contained here. Throughout this book, I hope to distinguish different approaches, concisely describe fundamental issues, and provide evocative cinematic examples. In every case, my overviews are not meant to be definitive; instead they are meant to provide clues for further exploration.

The primary intended readers for this book are students and non-professionals who have a love of movies and/or psychology. Therefore it is relatively jargon-free, and when I do use technical terms, I pause to explain them. All of the research traditions discussed in this book are grounded in essential film-related human phenomena about which many people are curious; my task is to reveal those kernels of widespread fascination to a broad audience. In addition, the book may be useful to individuals already familiar with certain areas of the psychology of film. By drawing connections between diverse areas of study, alternative avenues of exploration are suggested that may be instructive even for experts. Ultimately, my goal is to help as many people as possible more fully appreciate the movies in our midst.

My personal and professional background has prepared me well for this undertaking. Most importantly, I am a movie fan. Ever since biweekly trips to the grimy movie theater on the American Army post in Germany on which I grew up, I have loved the movies. When I returned to the US in my ‘tweens, I discovered the wonders of an ever-expanding cable revolution that made many movies easily available. In my teens, trips to the movie theater and VHS rentals were a critical part of both my social life and my alo...