eBook - ePub

Ancient Greek Philosophy

From the Presocratics to the Hellenistic Philosophers

Thomas A. Blackson

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Greek Philosophy

From the Presocratics to the Hellenistic Philosophers

Thomas A. Blackson

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Ancient Greek Philosophy: From the Presocratics to the Hellenistic Philosophers presents a comprehensive introduction to the philosophers and philosophical traditions that developed in ancient Greece from 585 BC to 529 AD.

- Provides coverage of the Presocratics through the Hellenistic philosophers

- Moves beyond traditional textbooks that conclude with Aristotle

- A uniquely balanced organization of exposition, choice excerpts and commentary, informed by classroom feedback

- Contextual commentary traces the development of lines of thought through the period, ideal for students new to the discipline

- Can be used in conjunction with the online resources found at http://tomblackson.com/Ancient/toc.html

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Ancient Greek Philosophy un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Ancient Greek Philosophy de Thomas A. Blackson en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Philosophy y Ancient & Classical Philosophy. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part I

The Presocratics

From 585 BC until Socrates (469–399 BC) changed the focus

The enlightenment, the inquiry into nature, and reason and experience

By about 550 BC, the Persian Empire had expanded westward. Greek cities in Ionia on the eastern shore of the Aegean, including Miletus, came under Persian rule. Ideas moved with refugees in advance of the Persians, north along the coast, to the southern part of mainland Greece (the Peloponnese), and to Sicily and southern Italy. This transmission of ideas continued during the Persian Wars. In 492, the Persians invaded the northern part of the Greek peninsula. In 490, against all odds, the Greeks were victorious at Marathon. The Persians launched a second invasion in 480, but they were defeated again, this time at sea. In the aftermath, Athens, who played a leading role in defeating the Persians, set up a league of cities, the Delian League, to clear the Aegean of Persian power.

Philosophy traditionally begins in 585 BC, the year of the solar eclipse which Thales of Miletus foretold. Thales was one of the leaders in the new inquiry into nature. This inquiry was a particular expression of the more general enlightenment attitude that human beings could know the truth about things, if they would think for themselves, rather than rely uncritically on the traditional habits of thought and received wisdom. The attempt to understand the inquiry into nature, as well as the enlightenment tradition more generally, gave birth to a philosophical tradition. It was thought that there are two kinds of cognition in human beings, reason and experience, and that knowledge of what exists is an exercise of reason, not experience. Moreover, it was thought that the inquiry into nature, when properly understood, employs reason to evaluate and possibly correct the traditional conception of reality, which is formed in experience and hence does not constitute knowledge of what exists.

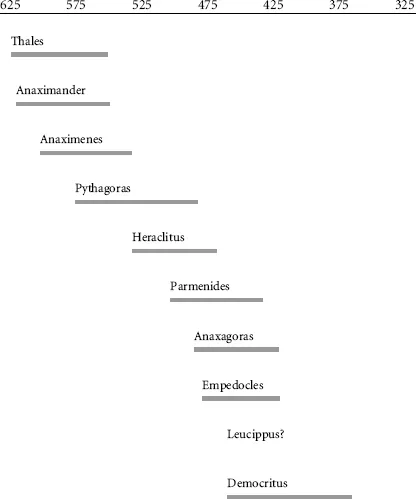

Time Line

The dates of the Presocratics are uncertain. Homer is traditionally dated to the eighth century and Hesiod to the eighth or early seventh century. Socrates lived from 469 to 399 BC.

Chapter 1

The Milesian Revolution

According to convention, philosophy begins in 585 BC. This is the year of the solar eclipse Thales of Miletus foretold. This prediction was significant because it was understood as an achievement of the enlightenment tradition that had taken root in the ancient world.15 Thales was the leading figure in a new field known as the “inquiry into nature.” This inquiry sparked a set of intense reflections which gave birth to a philosophical tradition as intellectuals tried to understand the issues raised by the inquiry into nature, and the enlightenment generally.

1.1 The Milesians Turn to Nature

Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes are the Milesian16 inquirers into nature. They were “naturalists.” They did not construct explanations in terms of the gods, as was the practice of the older school represented by Hesiod and the “theologists.” Instead, they explained things in terms of what they called a “nature.”17 Furthermore, rather than write in verse, as was the practice of the older school, they employed a new literary form to express their investigations. They wrote prose “inquiries,” the results of their work on a variety of subjects. The investigation into the past in the Histories of Herodotus is perhaps now the most well-known “inquiry,”1 but Thales and the Milesians were the first inquirers. They were inquirers into nature.

The new inquiry into nature was the most prominent example of the enlightenment attitude that had taken root in the eastern Mediterranean. It was thought that human beings could flourish, and get more and more parts of their lives under control, if they would think about things clearly and systematically, rather than rely so heavily on received wisdom and traditional ways of thinking about things. Thales and the Milesians directed this intellectual optimism to what now (in our debt to them) is said to be naturally occurring phenomena. They abandoned the older tradition represented by Hesiod and the theologists. In contrast, they thought that reality has a nature and that rain and other natural phenomena are manifestations of changes in this nature.18

The details of what the Milesians had in mind are difficult to determine because so little historically reliable evidence of their thought has survived.19 Indeed, a very substantial part of what is thought about these intellectuals depends on a report in Aristotle. He placed them within a longer history of philosophy, but he wrote this history not as history for its own sake, but as part of an introduction to a set of doctrines he presents in a work now entitled Metaphysics. In his report of what previous thinkers thought, Aristotle says that the “first lovers of wisdom,” by whom he means Thales and the Milesians, thought that something material is the starting point of all things:

Most of the first lovers of wisdom thought that principles in the form of matter were the only principles of all things; for the original source of all existing things, and that from which a thing first comes-into-being, and into which it is finally resolved (the substance persisting but changing in its qualities), this they declare is the element and first principle of existing things, and for this reason they consider that there is no absolute coming-to-be or passing away, on the ground that such a nature is always preserved … for there must be some natural substance, either one or more than one, from which the other things come-into-being, while it is preserved. Over the number, however, and the form of this kind of principle, they do not all agree; but Thales, the founder of this school, says that it is water. (Metaphysics I.3.983b = DK 11 A 2, A 122)

If Aristotle is right about Thales and the Milesian “school,” the naturalists and the theologists provide their accounts against different background conceptions of reality.

Anaximenes provides an example. He offered a new and revolutionary answer to the question of why drops of water sometimes form in, and subsequently fall from, the sky:

[Anaximenes says] that the underlying nature is one and infinite …, for he identifies it as air; and it differs in substantial nature by rarity and density. Being made finer it becomes fire; being made thicker it becomes wind, then cloud, and when (thickened still more) it becomes water, then earth, then stones, and the rest come into being from these. He too makes motion eternal and says that change also comes to be through it.3 (DK 13 A 5; Simplicius,20 Commentary on Aristotle's Physics)

The older theological answer to the question, the answer Hesiod gives in his poem Works and Days, takes the form of an explanation in terms of the mind of the god, Zeus. According to this account of the phenomenon, rain is a manifestation of Zeus' stormy mood:

1. Rain falls when Zeus the Storm King is stormy in mood.

2. Zeus the Storm King is stormy in mood. ———

3. It is raining.

Anaximenes, by contrast, shows no interest in any such answer that makes reference to the traditional pantheon of gods. Instead, he adopts the style of explanation that defines the new school of Thales and the Milesian naturalists. Anaximenes tries to explain rain as a condensed state of air. Put more formally, his explanation of rain may be recast as follows:

1. Rain is a state of the nature of reality: rain is condensed air.

2. The air here is condensed now. ———

3. It is raining.

On this account, the condition in the world that makes the sentence “It is raining” true is a state of nature with a certain history. In opposition to the theologists, rather than conceive of the signs for the coming of rain as an indication of Zeus' mood, Anaximenes seems to have thought of these signs as an indication of a sequence of events ending in the condensation of air.21

The Milesians left no record of how they arrived at the conception of reality Aristotle takes to underlie their explanations, but perhaps it was natural for them to think that the older explanations in terms of the traditional pantheon of gods were inadequate because really the behavior of the gods is determined by local customs and tradition.4 A more objective conception of reality was necessary. The question would be how to construct it, and a natural strategy would have been to revise the theological conception so that the pantheon is replaced by something independent of tradition. This might be accomplished by stripping the personal attributes from the notion of a responsible agent and applying the remaining idea of causation directly to reality.22 Reality would have a “nature,” and whether it rains, for example, would be up to reality, not because it has a mind and makes choices,5 but because rain is a function of changes in the “nature” of reality.6

This new conception of reality must have occurred as part of a more general attempt to reach a more secure understanding of things once people noticed and were bothered by the different theological traditions and their conflicts with one another. Since it is now difficult to take the accounts of Hesiod and the theologists seriously, it is necessary to keep in mind that the Milesian solution was not an immediate success. Reality did not appear the way they claimed it is. This, in turn, raised the question of how they knew that reality has a nature and that naturally occurring phenomena are manifestations of changes in this nature. The theologists had relied on a traditional source to validate their stories. They relied on the Muses.23 Hesiod relies on them in Works and Days and Theogony. This appeal to divine authority had traditionally gone unchallenged, but the new enlightenment attitude that had taken root in this part of the ancient world was making it increasingly difficult for intellectuals to have confidence in the traditional ways. Thales and the Milesians might have capitalized on this skepticism if they had offered arguments for their new inquiry into nature and its novel conception of reality, but this is something they apparently did not do.

This lack of justification prompted philosophical questions, both about the inquiry into nature and about the enlightenment assumption generally. To understand the case for the new inquiry into nature and its novel conception of reality, intellectuals began to ask epistemological and ontological questions. They asked questions about the kinds of cognition involved in knowledge, and they appealed to their answer to this question to help settle the original question of what really exists. In the surviving reports of what they wrote, Thales and the Milesian naturalists themselves do not explicitly engage in this philosophical project. Yet, it is clear as a matter of history that a deep and sustained interest in various philosophical questions soon emerged and took center stage as the intellectuals who followed the Milesians tried to understand both the inquiry into nature and the enlightenment assumptions. In this way, although Thales and the Milesians may have been more scientists than philosophers,7 their inquiry into nature gave birth to a philosophical tradition.

1.2 Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea24 is a towering figure in the new philosophical tradition.25 He took some of the first steps to understand the enlightenment contrast between thinking clearly on the one hand, and relying on habit and tradition on the other. He used his understanding to answer the question of what exists, the question to which the Milesians had given such a revolutionary answer.

In his poem, certain parts of which are difficult to understand, Parmenides distinguishes three paths for inquiry in the search for knowledge. He identifies the path to knowledge as “the path of Persuasion” that “attends Truth.” This is the path corresponding to “it is”:

And the goddess greeted me kindly, and took my right hand in hers, and addressed me with these words: Young man, you who come to my house in the company of immortal charioteers with the mares which bear you, greetings. No ill fate has sent you to travel this road – far indeed does it lie from the steps of men – but right and justice. It is proper that you should learn all things, both the unshaken heart of well-rounded truth, and the opinions of mortals, in which there is no true reliance. (DK 28 B 1; Sextus Empiricus,26 Against the Professors VII; Simplicius, Commentary on Aristotle's On the Heavens)

Come now, I will tell you (and you must carry my account away with you when you have heard it) the only ways of inquiry there are for knowing.8 The one, that it is and that it is impossible for it not to be, is the path of Persuasion (for she attends upon Truth); the other, that it is not and that is needful that it is not, that I declare to you is an altogether indiscernible track; for you could know what is not … (DK 28 B 2; Proclus,27 Commentary on Plato's Timaeus; Simplicius, Commentary on Aristotle's Physics)

It is not at all clear what Parmenides means by “it is,” but the main line of thought is reasonably straightforward. He thinks that “it is” corresponds to the path to knowledge but that the inquirers into nature have taken a different path. Thei...