eBook - ePub

Osteopathy and the Treatment of Horses

Anthony Pusey, Julia Brooks, Annabel Jenks

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Osteopathy and the Treatment of Horses

Anthony Pusey, Julia Brooks, Annabel Jenks

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Written by pioneering and internationally-renowned specialists in the field, this text provides clinically-orientated information on osteopathy as a treatment for horses. It explains the scientific rationale of how osteopathy works in animals, as well as providing a detailed working guide to the technical skills and procedures you need to know to perform safe and effective osteopathic procedures.

- Drawing on well established practices for humans this book provides details on the full variety of diagnostic and therapeutic osteopathic procedures that can be used on horses.

- Full of practical information, it demonstrates how professionals treating equine locomotor problems can adapt different procedures in different clinical settings.

- Over 350 colour images and detailed step-by-step instructions demonstrate the procedures and practice of osteopathy.

- Covers treatment both with and without sedation and general anaesthetic.

This comprehensive text is written for students and practitioners of osteopathy with an interest in treating horses. It will also be useful to other allied therapists, and to veterinary practitioners who want to know more about the treatment of musculoskeletal problems.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Osteopathy and the Treatment of Horses un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Osteopathy and the Treatment of Horses de Anthony Pusey, Julia Brooks, Annabel Jenks en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medizin y Pferdemedizin. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

Introducing Osteopathy for Horses

On a blustery Friday evening in the depths of a particularly long winter, I had just finished an afternoon’s list of patients when the telephone rang. I lifted the receiver.

‘It’s Jack’, said someone urgently. ‘He’s lying on the kitchen floor, howling with pain. Can you come out to him?’

I recognised the voice of a patient whose family I had seen intermittently over years and, following the directions given, I arrived at the threshold of a terraced cottage. There was indeed an awful racket coming from inside and my concern for poor Jack deepened. As I was ushered hastily into the kitchen, I was confronted with a very large, shaggy German Shepherd dog obviously in considerable pain!

In response to my questioning gaze, Jack’s owner looked apologetic and confessed that he had not been entirely frank on the telephone as he doubted that, if he had, I would have consented to the visit. He added in flattering tones that as I had treated the rest of the family so successfully, he was sure that I would be able to help his dog.

It transpired that Jack had suffered recurrent bouts of back pain over a number of years, which had reached a crisis point that afternoon after he had leapt down from the back of the car. The pattern of presentation was one that I recognised from human practice.

I called for help. By chance, the family vet was also a patient of mine and, after talking about Jack’s problem in particular and musculoskeletal problems in general, he readily admitted that all he would offer in such cases was symptomatic relief in the form of painkillers and antiinflammatory drugs. We decided on a combined approach to Jack’s treatment. In the following years there were many other animals that benefited from our shared experience on a kitchen floor all those years ago.

After Jack, my experience of using osteopathy with animals broadened, to include a variety of species including a prize-winning pig and a film-star camel.

The animal work has brought innumerable benefits to my human practice. It has sharpened my observational skills of the body both at rest and in motion. It has taught me to rely on the findings of my fingers. It has refined my diagnostic reasoning. I have benefited from contact with other professions whose skills and ideas provide an added dimension to my work as an osteopath. It has also brought the friendship of other osteopaths working in the field, whose dedication and enthusiasm have been palpable.

Formany osteopaths,much of their animal work involves horses, apparently heedless of the warning issued by a well known farrier that horses are ‘dangerous at both ends and uncomfortable in the middle’.We decided to write this book to introduce the subject and encourage contributions from current practitioners and future generations as knowledge and expertise in this field develop.

It is therefore the intention to provide a theoretical and practical framework for students and practitioners with an interest in the osteopathic treatment of the horse. It will also be helpful to allied professions such as veterinary surgeons, other musculoskeletal specialists, farriers, equine dentists and saddlers to introduce some of the concepts underlying osteopathic treatment and enable them to identify the cases where osteopathy may benefit animals in their care.

A history of the development of animal treatment has been included, as well as the legal and ethical aspects to be considered when working in this field. Anatomical, biomechanical and neurophysiological principles on which osteopathic treatment of horses is based have been discussed and a diagnostic and therapeutic approach has been proposed.

Figure 1.1 Andrew Taylor Still (1828–1917), father of osteopathy (right) with author Mark Twain.

This approach is by no means prescriptive. Each practitioner will develop their own diagnostic routines and therapeutic techniques, according to training, experience and preference. In this diverse and challenging field there is a place for everyone.

HISTORY OF OSTEOPATHY

To begin at the beginning is to take a leap back into antiquity. Over 2500 years ago, Hippocrates advised that ‘a physician must be experienced in many things, but assuredly in rubbing’. Over the centuries that followed, many forms of physical treatment have been shown to be beneficial.

Osteopathy as a medical philosophy was developed in the 1880s by Andrew Taylor Still, a doctor from the American mid-west (Figure 1.1). Dr Still became disillusioned with the medicine practised at that time, which included bleeding, purgatives and other equally unpleasant forms of treatment. Instead, his anatomical studies led him to envisage a system of medicine that placed chief emphasis on the structural integrity of the body as being vital to the well being of the organism. In other words, if the structure is fine, then the body can function normally. Over the years, a number of definitions of varying length and complexity have been proposed for osteopathy, but Dr Still’s original concept has largely been preserved.

LEGISLATION

If human medicine was basic in the time of Dr Still, then the care of animals was also less than satisfactory. In early years the treatment of horses was the responsibility of farriers, regulated in England by the Worshipful Company of Farriers established in 1674. However, they competed with cow-leeches and horse doctors in applying uncomfortable and invasive treatments such as oiling, firing and rowelling, and prescribing toxic substances, of which antimony and sulphur were particularly popular. In 1844, the Royal Charter for the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons advocated that horses should be treated by veterinary surgeons. Over the following decades, farriers reverted to specialising in the craft of shoeing horses, and those trained at the new veterinary colleges undertook the treatment of animals.

In the 20th century, all professions moved towards the regulation of training and practice. For osteopaths in America this meant merging with the medical profession in the 1960s. In England, osteopaths preserved their identity as an independent profession, and the Osteopaths Act of 1993 restricted the title of osteopath to those who had fulfilled the necessary training required by the General Osteopathic Council.

Similarly, the Veterinary Surgeons Act of 1966 made it illegal for anyone other than a veterinary surgeon to treat an animal. An exception to this was physical therapists. This category included physiotherapists, chiropractors and osteopaths, who could treat an animal under the direction of a vet. This recognised the contribution of physical treatments made by these disciplines. It also provided protection for animals in terms of early diagnosis of pathological processes and preventing inappropriate treatment.

HISTORY OF OSTEOPATHIC TREATMENT OF ANIMALS

Recognition of osteopathy as a healing system spread and it soon became clear that a treatment apparently so successful in humans could be applied with equal success to the treatment of animals.

Many of those regarded as forerunners in the field were osteopaths practising in the first half of the 20th century. The stories of the way they started will reflect a common experience in the generations that followed. Some began after a request from a patient to look at a family pet; others began in response to the suffering of their own animals. Colin Dove, a former principal at the British School of Osteopathy, remembers applying his cranial expertise to treat a colleague’s dog that was crippled after an afternoon cavorting with his children! Osteopaths in rural areas were approached by farmers concerned about their various animals. Practitioners such as Greg Currie in Epsom were inevitably drawn into the racing world.

For some these will have been one-off or infrequent experiences, but for others it was a launching pad into an exciting, challenging and rewarding field. One of the pioneers in the field, working alongside vets, was Arthur Smith (Figure 1.2). Arthur qualified in 1951 from the British School of Osteopathy and set up practice in Leicestershire. One of his patients was a vet who, having felt the benefit of osteopathic treatment for himself, asked whether the principles could be applied to horses. Initially reluctantly, he took time out to study horse anatomy at a local museum and decided that it might be possible. After successes with the first few cases, veterinary surgeons referred hundreds of horses to him over subsequent years. In his retirement he described vividly techniques that involved a general anaesthetic and six strong men!

Figure 1.2 Arthur Smith (centre): a pioneer in the osteopathic treatment of horses under general anaesthetic.

Society of Osteopaths in Animal Practice (SOAP)

In the early 1980s, in response to increasing interest from the general public and the profession itself,Mr Barry Darewski, the registrar of the regulating body, the General Council and Register of Osteopaths (GCRO), asked for a list to be compiled of osteopaths with a special interest in treating animals. This list formed the core members of the special interest group, Osteopaths in Animal Practice (OAPs) which was to become SOAP (Society of Osteopaths in Animal Practice) in 2004.

This group and the osteopathic schools have assisted in sharing knowledge in this field through postgraduate education. Interdisciplinary communication with vets, physiotherapists, chiropractors, farriers, dentists and saddlers has flourished in this environment. Institutions such as zoos, the army and the police have also come to appreciate the contribution osteopathy can make to animals in their care. More recently, the advantages of research in this area have become evident in demonstrating the effectiveness of osteopathy in subjects not susceptible to placebo.

With the growth and development of this field, osteopathy has been shown to make a valuable contribution as part of a multidisciplinary team devoted to the care of animals. It is also an exciting and rewarding part of the rich tapestry that is osteopathy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hunter P (2001) Researching the past: archival sources for the history of veterinary medicine. In: Rossdale PD, Green G (eds) Guardians of the Horse II. Romney Publications, Newmarket, pp. 34–39.

Osteopaths Act 1993. HMSO, London.

Prince LB (1980) The Farrier and His Craft. JA Allen, London.

Still AT (1902) The Philosophy and Mechanical Principles of Osteopathy. Hudson-Kimberly, Kansas City.

Veterinary Surgeons Act 1966. HMSO, London.

2

Horse Anatomy for Osteopaths

The anatomy of the horse is a huge subject. It is certainly not possible to squeeze it into a few pages, which is why this chapter will concentrate on some of those aspects that may be useful in osteopathic practice. For the rest, it is a case of studying some excellent but weighty anatomical tome, of which there are many. Another useful way of extending anatomical knowledge is to beg a body part from a knacker’s yard and dismember it with the aid of a dissection guide. Care should be taken with storage, however. A colleague who was to have provided a horse’s head for a study group had it dragged from his garage and away over the fields by a gourmet fox. Fortunately, he was able to provide ‘an old one’ from his deep freeze!

This text will concentrate on the basic structure, the surface anatomy and the regional anatomy insofar as these have clinical and osteopathic relevance.

OVERVIEW

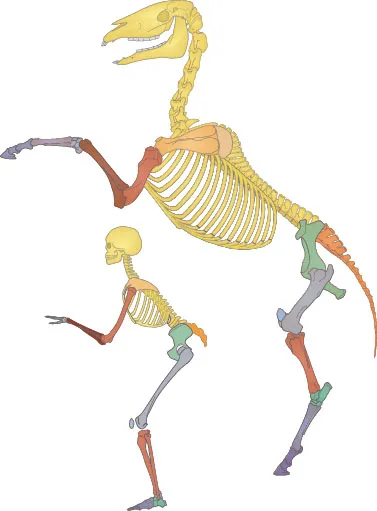

If some of the anatomical volumes seem a little daunting, there should not be cause for complete despair. Those who still remember human anatomy will appreciate the remarkable similarity in the basic structure between the species (Figure 2.1). The differences are mainly those of scale, proportion and orientation. Also, horses do not have clavicles and have fewer fingers and toes.

The main structural difference is in the legs. It is as though someone has grabbed hold of the third metacarpal and third metatarsal where they join the carpal and tarsal bones respectively, and pulled them out, so elongating them and losing most of the fingers in the process. This means that the carpal bones, instead of being situated towards the end of the limbs as in the human, actually end up towards the middle of the limb. Many of the bone and joint names will sound familiar (Figure 2.2). However, one trickier vagary of nomenclature is that vets refer to the carpal joints in the middle of the forelimb as the knee, which is actually the wrist in human terms. The human idea of the knee, complete with patella, is actually found tucked up at the upper end of the hindlimb and is called the stifle. ‘A knee in the groin stifles all comment’ may help as an aidem émoire!

Ossification rates of bones are also different. Growth continues up to 4 years and some adjacent ossification centres do not unite until 30 years old, if at all. This should be borne in mind when looking at X-rays to avoid the classic mistake of thinking that an epiphyseal plate or suture is a fracture line.

Muscles that will be recognisable from human studies may be better developed in the horse and have a different orientation to reflect its function as a grazing quadruped. Anatomists have managed to make things slightly more awkward by naming a few things differently, and a number of these names have been changed over time. Some of the muscles are called by alternative names, but as the terminology generally describes the origin and the insertion this should not prove to be too much of a problem.

Body orientation is also different in quadrupeds. The horse stands with around 60% of its body weight through the front limbs, with recent texts indicating a centre of mass at the level of the 13th rib along a line extending between the points of the shoulder and buttock. This explains the observation that, while resting one or other of the hind limbs may be normal, not weight-bearing through a forelimb is usually an indication that there is something wrong.

Figure 2.1 Horse and human skeleton: similarities are remarkable and differences are largely of scale, proportion and orientation.

ANATOMICAL DESCRIPTORS

With all four limbs in contact with the ground, some of the anatomical positional terms will be different and so a quick review of descriptive terms may be helpful (Figure 2.3). Planes that face towards the ground, such as the abdominal surface, are described as ventral while those directed skywards are dorsal. Anything facing forwards is referred to as cranial, and backwards as caudal. This also applies to the legs until, below the carpals and tarsals, the forward-facing part of the limb is the dorsal surface and the backward-directed parts become palmar and plantar surfaces respectively. At the head, structures towards the nose are considered to be rostral.

Proximal parts of the limb are located towards the trunk, while distal parts are found at the end of the limb. Other terminology to be aware of includes medial (directed towards the median plane) and lateral (towards the outside of the body).

Descriptions often refer to anatomical planes. The median plane describes a slice taken through the midline of the body from poll to tail, dividing the body equally into left and right halves. Sagittal planes are those running parallel to the median line. The dorsal or frontal plane divides the body into dorsal and ventral portions. Transverse planes are slices at right angles to the median plane of the body or to the long axis of a limb.

When it comes to describing planes of movement, flexion is where opposing surfaces approximate and extension is where surfaces separate. Sidebending, familiar in human terminology, is referred to as lateral flexion.

The following text outlines the regional anatomy of the head, neck, back and limbs with reference to surface features and structural components and touching on areas susceptible to dysfunction and pathology.

THE HEAD

Overview

The head is a large, elongated structure. It provides a considerable surface area for muscle attachments and to accommodate teeth so that horses can do efficiently what horses like doing best: eating. The head is also heavy, whichmeans that, by moving up, down and side to side, it can be used very effectively as a kind of weighted bob to change the horse’s centre of gravity and induce momentum during movement (Figure 2.4).

Surface Anatomy

Observable and palpable features include the poll (nuchal crest) from which runs the external or parietal crest. Laterally, the facial crest gives an attachment for the powerful masseter muscle, and the infraorbital foramen conveys a branch of the maxillary nerve to the upper lip. Medially, the nasal peak lies between the nasoincisive notches. On the mandible, rostral and medial to its angle, is a vascular impression that carries the facial artery, vein and parotid duct and is a site often used for taking a pulse. Further along, the mental foramen carries branches of the alveolar nerve to the lower lip.

Anatomical Components

The skull can be divided into two regions by a transverse line through the orbits: the cranium and the face.

The Cranium

The cranium, forming only a small part of the skull, contains a brain of about 600 g, which compares unfavourably with the 1300 g human organ. It lies in the area between the poll (nuchal crest...