THE KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY TRANSFORMATION

Over the past several decades, economies in the United States and across the developed world have increasingly become knowledge-driven. Powell and Snellman (2004) define the knowledge economy as “production and services based on knowledge-intensive activities that contribute to an accelerated pace of technical and scientific advance” (p. 199). The emphasis in a knowledge economy is on knowledge and skill-based inputs and outputs rather than physical inputs and outputs. As is discussed in Chapter 2, however, this transformation is only the most recent in a series of economic reorganizations over the centuries.

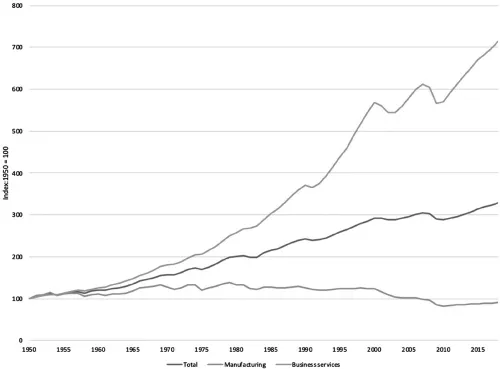

The transformation to a knowledge economy has substantial implications for the way work is done, the employment growth of individual industry sectors, the skills required of workers, and the meaning and measurement of capital. The transformation’s impact on employment is shown in Fig. 1. This chart compares national employment growth since 1950 of manufacturing, the key production sector, professional and business services, a major knowledge-producing sector, and total employment. Both employment totals are set equal to 100 in 1950, and cumulative percentage employment changes since then are charted.

Fig. 1. The Shift from Manufacturing Employment to Professional and Business Services Employment in the United States, 1950–2017.

Source: United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019).

In 1950, manufacturing employed 14 million workers, nearly one-third of total employment. The 2.9 million workers in professional and business services, meanwhile, comprised 6.5% of employment. Beginning in the late 1950s, manufacturing employment growth began to trail total employment growth. A secular decline in employment began in the early 1980s; manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 at 19.4 million. By 2018, manufacturing employed 12.7 million workers, 8.5% of total employment and a smaller job total than in 1950.

In contrast, professional and business services’ employment growth accelerated in the late 1950s, at the same time as manufacturing employment growth began to lag. The sector’s rise has suffered only two noteworthy setbacks: the first due to the dot-com bust of the early 2000s and the second driven by the severe 2007–2009 recession. Despite these two relatively brief declines, professional and business services employment has increased more than sevenfold since 1950 and stood at 21 million in 2018, 14% of total US employment.

There is a danger in these discussions of falling into the trap of defining knowledge in terms solely of high-skill occupations, such as attorneys, scientists, economists, and college professors. In fact, the knowledge economy extends to virtually all industries and occupations. It includes the ability of a factory worker to program and operate a computer numerical control machine, a hairdresser to give a client a permanent, a plumber to find and correct a leak, and a salesperson to provide excellent customer service. In every case, the application of knowledge has created value for the organization. This perspective of knowledge jobs as necessarily high-skill arises from the implicit devaluing of so-called “middle-skill jobs” and emphasis on four-year degrees as the only path to professional and financial success. This has led to a severe shortage of skilled-trade workers as older workers retire. Compounding this problem is the fact that the US Census Bureau, unlike comparable agencies in Europe, tracks educational attainment solely on the basis of diplomas and degrees, not licenses and certifications. There is no centralized source for the number of these credentials.

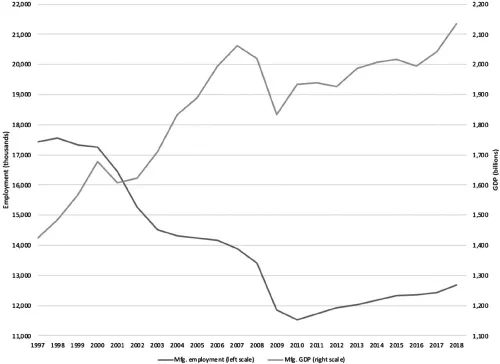

Consider the impact of knowledge on the manufacturing sector, as shown in Fig. 2. This chart graphs the trends in employment and inflation-adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) of manufacturing between 1997 and 2007. GDP is not the total value of manufactured products; rather, it is the value added during the manufacturing process. The final price of fabricated steel products, for example, includes not only the manufacturing inputs, but also the inputs of mining, transportation, wholesaling, and possibly retailing as well. In contrast, GDP isolates the activities of manufacturers.

Fig. 2. The Relationship between Manufacturing Employment and GDP, 1997–2007.

Source: United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019) and United States Bureau of Economic Analysis (2019).

The period charted begins late in the boom of the 1990s, continues through the relatively mild 2001 recession, the expansion of 2001–2007, the severe recession of 2007–2009, and ends during the expansion that began in 2009. The period from 1997 to 2010 was one of stagnant then sharply declining manufacturing employment. This trend caused considerable consternation in the popular press and among the political class. The argument was that based upon the employment declines, American manufacturing was dying and being exported in its entirety overseas. But the increase in the marginal value of US manufacturing output reveals the fallacy of this argument. Simultaneously with a 20% decline in manufacturing employment, there was a 45% increase in the value of US manufacturers’ production. Productivity of manufacturing workers – defined as the value of output per worker – increased 81%.1 This trend continued through the recession even as output fell. Between 2007 and 2009, employment declined 15% as GDP fell 11%, yielding a productivity increase of 4%. Jobs were not being exported overseas; rather, they were disappearing altogether as technology and robotics took on tasks formerly performed by workers.2

This relationship has been less clear-cut after the recession. Beginning in 2010, manufacturing employment began to grow – its first sustained employment increase since the 1960s. Employment increased 7% between 2010 and 2018 as GDP increased 16%, yielding a net productivity increase of only 9%. This represents an annual growth rate of 0.9%, less than one-sixth the rate between 1997 and 2007.

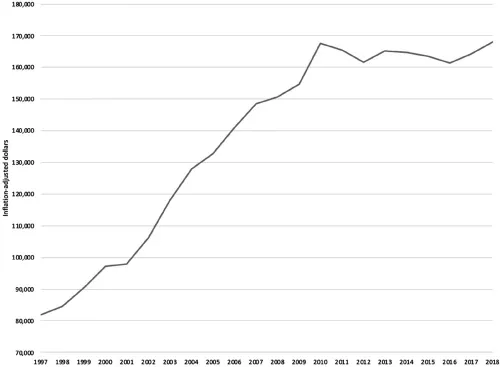

The time trend of productivity is charted in Fig. 3, which shows a clear break in 2010. In contrast to the steady growth in earlier years, the trend after 2010 has been erratic. Productivity suffered declines in 2011, 2012, and 2014–2017. In fact, the only reason that there was a net increase in productivity between 2010 and 2018 was a 2.4% gain in the final year.

Fig. 3. Manufacturing GDP per Worker, 1997–2018.

Source: United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019) and United States Bureau of Economic Analysis (2019).

This shift to technology in manufacturing has led to a substantial change in the knowledge demands placed upon manufacturing workers. As these workers interact with the technology, they need to understand how the technology works and how to remedy the situation if a problem occurs. The shifting environment within manufacturing operations has led to additional skill demands as well. The Chief Executive Officer of a manufacturing plant in southeastern Ohio told one of the authors that he expects all of his new hires to have leadership ability, or at least the potential to develop it. Manufacturing in that plant, and in many other plants, occurs in a team environment, and those teams need leaders.

Knowledge has impacted the manufacturing process in a variety of ways. Engineers develop an understanding of the manufacturing process and design machines and computers to automate it. Human resource researchers and professionals study the process, determine the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed by workers to perform successfully in the process, and recruit those workers. Managers and team leaders ensure the efficient day-to-day operation of the process, and the workers implement the process.

There are existing and emerging transformations in other fields as well. The transformation in agriculture, which is discussed in Chapter 2, is at least as profound as that in manufacturing. Retail has been impacted not only by online shopping but also by barcode scanners that originally increased the efficiency of checkout clerks by allowing them to scan rather than operate a cash register keypad, and eventually eliminated many of them altogether with the advent of self-scanning checkout lines. The improvement of telephone technology rendered switchboard operators obsolete, and the advent of word processors and personal computers eliminated the secretarial pool. Artificial intelligence that evaluates and generates routine legal documents may endanger attorney positions, and self-driving technology is likely eventually to replace truck drivers. All of these transformations rely on knowledge, whether external to the organization or internal, to facilitate the production process.

The need to take full advantage of the transformation and to manage its impacts on the economy, firms, and skills of workers requires that business leaders and policymakers understand the changes and plan for them. That is the objective of this book.

KNOWLEDGE VERSUS DATA AND INFORMATION

The term “Information Age” is widely used to characterize the shift described above. The Oxford English Dictionary (2019) cites the first use of the term by Richard S. Leghorn in 1960. At this time, mainframe computers were gaining more widespread usage in industry and academia. Despite the fact that the personal computer was still a decade and a half in the future and horror stories multiplied of catastrophic errors in customer data that never seemed to get corrected, these early computers unquestionably facilitated the transformation. With the development of the internet, and as computing power grew to the point that it became possible to manipulate massive quantities of data and combine multiple data sets (“big data”), the value of data increased markedly.

However, it is important to distinguish among data, information, and knowledge. Data are collections of facts and statistics. When these data are collected and systematized, they become information. Knowledge is gained when the information is applied to reveal insights and relationships in order to understand some problem or phenomenon. According to Guerra-Zubaiga and Young (2008):

Data relate simply to words, symbols or numbers without a context or interpretation to provide meaning. Information is a collection of data which is processed and structured in such way that receives particular meaning within a context. Knowledge has many possible interpretations; knowledge is information with added detail related to how it should be used; knowledge exists when a user within a specific context recognizes useful data relationships or when a user is able to derive those relationships from raw, but structured information. (p. 183)

An example might be labor force data. The labor force total, number of residents employed, number unemployed, and unemployment rate are data. When the data are seasonally adjusted to make month-to-month comparisons meaningful and are put in a table, they become information. When the information is analyzed to explain why the unemployment rate has been declining – whether because more people are working or fewer people are looking for work – and the implications of that finding for the economy, knowledge is produced.

Fig. 4. Relationships among Data, Information, and Knowledge.

These relationships are diagrammed in Fig. 4.