eBook - ePub

The American Vitruvius

An Architects' Handbook of Urban Design

Werner Hegemann, Elbert Peets, Christiane Crasemann Collins

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 320 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The American Vitruvius

An Architects' Handbook of Urban Design

Werner Hegemann, Elbert Peets, Christiane Crasemann Collins

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This atlas of architectural design advocates rational as well as humanistic principles in the development of the urban environment. Drawing upon the ideals that inspired the great Roman architect, it promotes the Vitruvian maxims of longevity, beauty, and commodity. It also defines the thinking behind modern American city planning.

First published in 1922, The American Vitruvius arose from a collaboration between two students of American urbanism. Werner Hegemann, an urban planner, and Elbert Peets, a graduate of Harvard's School of Landscape Architecture, selected more than 1,200 plans, elevations, and perspective views. Their choices depict a tremendous variety of European and American structures dating from the Renaissance to the early twentieth century. Ranging from Rome's vast Piazza San Pietro to modest German and English garden suburbs, this volume explores all manner of urban design, including American college campuses, parks, and cemeteries; L'Enfant's plan of Washington, DC; and other civic centers.

Design Book Review hailed this classic as `the most complete single-volume survey of canonical cases of urbanism,` offering `a scintillating collection of uncommon and forgotten designs.` An essential reference for every architect and student of architecture, this affordable edition is of particular value in light of the current New Urbanism trend.

First published in 1922, The American Vitruvius arose from a collaboration between two students of American urbanism. Werner Hegemann, an urban planner, and Elbert Peets, a graduate of Harvard's School of Landscape Architecture, selected more than 1,200 plans, elevations, and perspective views. Their choices depict a tremendous variety of European and American structures dating from the Renaissance to the early twentieth century. Ranging from Rome's vast Piazza San Pietro to modest German and English garden suburbs, this volume explores all manner of urban design, including American college campuses, parks, and cemeteries; L'Enfant's plan of Washington, DC; and other civic centers.

Design Book Review hailed this classic as `the most complete single-volume survey of canonical cases of urbanism,` offering `a scintillating collection of uncommon and forgotten designs.` An essential reference for every architect and student of architecture, this affordable edition is of particular value in light of the current New Urbanism trend.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The American Vitruvius un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The American Vitruvius de Werner Hegemann, Elbert Peets, Christiane Crasemann Collins en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Arquitectura y Ensayos y monografías sobre arquitectura. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

ArquitecturaCHAPTER I

The Modern Revival of Civic Art

The engravings accompanying this chapter were mainly used by Camillo Sitte (of whose book the chapter is largely a synopsis) to illustrate his teachings and to serve as the basis upon which those teachings were built up. They are taken, for the most part, from the French edition of Sitte. Others, of which the sources are usually given, supplement Sitte’s illustrations or represent designs which are known to have influenced him. Some of Sitte’s own work is reproduced and one design by his followers. The small plaza plans are mostly at a scale of 330 feet to the inch.

Civic Art is a living heritage from classic, medieval and Renaissance times. Before starting, however, upon the road which seems destined to lead it to such high architectural achievements in twentieth century America, it went through a period of utter decline during the nineteenth century. The revival dates from the comparatively recent discovery that the customary gridiron street planning of most American cities, as well as the diagonal (or triangular) and radial street planning of Baron Haussmann’s Paris or even of L’Enfant’s Washington, to take two much praised examples, produce very unsatisfactory settings for monumental buildings. While many modern critics are unduly hard upon the gridiron system they frequently are still biased, especially in America, in favor of the diagonal or radial systems. But radial or triangular systems are like the gridiron system in having at the same time practical advantages and disadvantages and in producing esthetically satisfactory results only if handled with much discretion and taste. The wisely handled gridiron system as found in the original plans for Philadelphia, Reading, and Mannheim offers charming possibilities which should not be overlooked by critics to whom Baron Haussmann’s work in Paris appears to be flawless. Indeed close students of Haussmann’s engineering, which involved Paris in an expenditure of two billion francs, have frequently denounced it. One of the most interesting documents in this connection is the crushing criticism made in 1878 by Charles Gamier, the great designer of the Paris Opéra, of the failure of Baron Haussmann’s methods to provide a satisfactory setting for the Opéra (Figs. 16 and 17; further illustrations in next chapter). Parts of Garnier’s moving utterance deserve to be quoted, as it ought to have special weight with those American architects who are in sympathy with the traditions of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts of which Garnier was a star disciple. In order to appreciate how gigantic was the failure of Haussmann in connection with the Opéra site it is well to remember, before reading Garnier’s criticism, that Thiers, shortly before his assuming office as the first president of the French republic, in a memorable address on city planning directed against Haussmann. especially dwelt on the latter having spent thirty millions for the mere preparation of the Opéra site. If Haussmann’s work, which aimed mainly at military, sanitary and engineering objects, should at all be judged from an esthetic point of view, the setting of Garnier’s Academy of Music is the most ambitious piece of it.

This is what the architect whose building stands on the site prepared with such great effort, has to say about Haussmann’s esthetic achievement:

“I know of no monument, ancient or modern, which was set amidst surroundings more deplorable than those of the new Opéra! Of some the view has been obstructed, others are almost hidden, still others stand on steep hills or in deep holes; yet all of them, be their setting what it may be, at least are spared from having to fight against surroundings which are regularly irregular, against houses larger than they are, against viewpoints whence foreground, sides, and background are banal buildings, ill-placed and symmetrically criss-crossed, and against open areas too small to set the monument free and too large to give it scale! The Opéra is, in a word, jammed into a hole, pushed back, and buried in a quarry! and, truly, if I hadn’t such a real admiration for the great things M. Haussmann has done, I should feel a furious rage against him! But, as I have had time to calm myself since he chopped the region of the Chaussée-d’Antin up into triangular fragments and put a hump in the roadway of the Boulevard des Capucines at the same time that he cut a notch out of the Boulevard Haussmann, when he ought to have done just the contrary, I console myself with the thought that in some hundreds of years there shall come to Paris a prefect who shall have (as ours have, nowadays) a desire to disengage the monuments of the Paris of those times, and that he will be inspired to disencumber the Opéra by razing the whole region! . . .”

“Whatever it may be in the Paris of the future, the Opéra of the present is surely ill placed; the site upon which it is built is narrow in front, narrow in back, and bellies out in the middle, in such a sort that the enclosure of the site, having to follow its outline, seems to hold its arms akimbo like a paver’s ram; also, and still more terrible, the site has a side-slope and forcibly drags with it, in its descent, that same unhappy enclosure, which clings to nothing at all and which, instead of serving as frame to the monument, produces the effect of a picture propped up at an angle in the very center of a salon!”

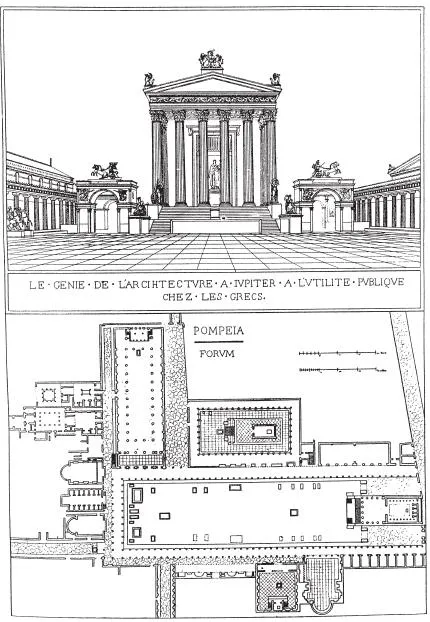

FIG. 19—THE NEW FORUM IN POMPEII

Reconstructed view and plan (from J. A. Coussin, 1822). The less attractive but probably more correct reconstruction published by Sitte gives two stories to the colonnades surrounding the forum.

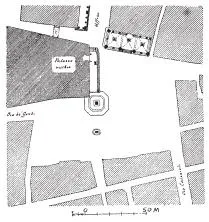

FIG. 20—PIAZZA DELLA SIGNORIA, FLORENCE

This is the plaza around which Michelangelo proposed a scheme of arcades continuing the Loggia del Lanzi (illustrated Fig. 798). (From Brinckmann.)

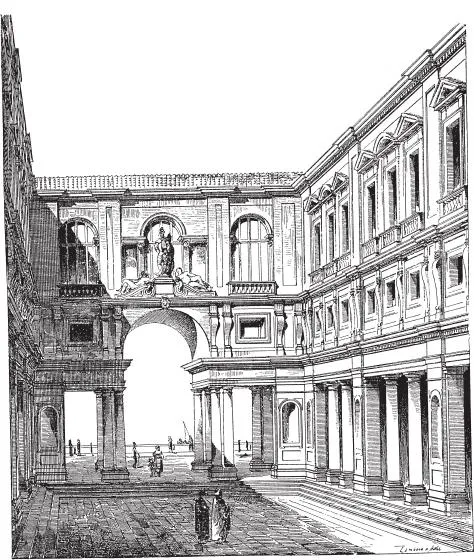

FIG. 21—PORTICO DEGLI UFFIZI, DESIGNED BY GIORGIO VASARI, 1560.

This gate opens to the river; the other end of the colonnaded court opens on the Piazza della Signoria as indicated in the plan, Fig. 20.

Garnier continues, incidentally giving some ideas on city planning characteristic of his period, to which it will be interesting to refer in a later part of this chapter, and he concludes with the following sarcastic remarks about the customary failure to grant the architect sufficient influence in the development of the site he has to build upon:

“I was consulted, to be sure”, says Garnier, “for at least five minutes” —in 1861 when the plans were taken to the Tuileries. The Emperor asked Garnier’s opinion of the site. Garnier regretted “the triangular form given to all the blocks of houses.” The Emperor agreed and chided Haussmann with an overfondness for “fichus”. “His Majesty even made with his own hand a sort of little sketch on the plan of the vicinity, eliminating the bias streets and substituting rectangular plazas, and I felt sure that with this imperial protection some change in the project would be made.” But the triangles were built, just the same, and when Garnier remonstrated on the occasion of the Emperor’s only visit to the work, in 1862, “His Majesty Napoleon III answered me exactly thus: ‘In spite of what I said, in spite of what I did, Haussmann has done as he pleased! ! . . .’ And to think that it is perhaps always thus that a sovereign’s will is done!”

The problem of the Paris Op...