![]()

I

Sunlight and Shadows

1. Sun-Pictures

In the shade of a group of trees we see on the ground a number of spots of light, scattered irregularly, some large, some small, but all of them of a similar elliptical shape. Hold a pencil in front of one of them; the line connecting pencil and shadow indicates the direction from which the rays of light come that make the little patch on the ground. It is, of course, the sunlight piercing through an aperture in the crown of the tree; our eye sees a dazzling brightness here and there among the leaves.

The surprising thing is that all these spots have the same shape, and yet it is unlikely that all those chinks and openings should happen to be so nicely similar and round ! Intercept one of these images by a piece of paper, held at right angles to the rays, and you will see that it is no longer elliptical, but circular. Raise the paper higher and the spot grows smaller and smaller. So we conclude that the pencils of light forming such a spot have the shape of a cone and the spots are elliptical only because the ground cuts this cone slantwise.

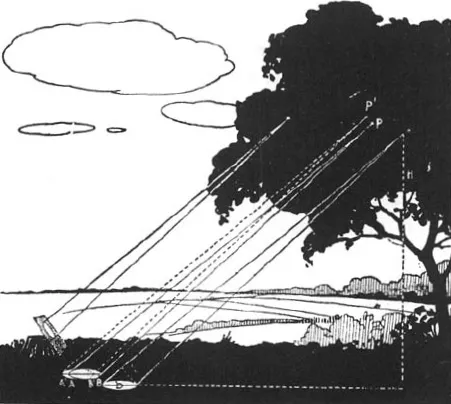

The origin of this phenomenon is to be found in the fact that the sun is not a mere point. Any very small opening P (Fig. 1) forms a small, well-defined image of the sun AB; another small opening P′ gives a somewhat shifted image A′B′ (dotted lines); a wider opening, which contains both P and P′, gives a less sharp but brighter image of the sun A′B. We can indeed see spots of light of every degree of brightness, and if there are two of equal size, the brighter one is at the same time the less sharp.

In confirmation of this, notice that when clouds pass before the sun you can see them glide over each patch of sunlight, but in the opposite direction; during a partial eclipse of the sun, all the sun-pictures are crescent-shaped. When there is a large sunspot it is visible on the sharpest images of the sun. You can make a very well-defined image of the sun by piercing a small, perfectly round hole in a sheet of thin cardboard, and holding it up so that the sun’s image falls on a well-shaded spot.

FIG. 1. Sun’s rays penetrating dense louage.

Examine the image of the sun formed at various distances by a square aperture.

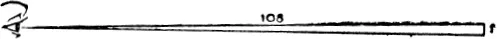

The angle subtended by the sun’s disc must be, therefore, the angle APB at the vertex of the cone forming the sun’s image. Small angles of this kind we often measure in radians. We say, ‘That angle is

radian,’ meaning that the sun seems to be as large as 1 inch at a distance of 108 inches, or as large as 10 inches at a distance of 1,080 inches (

Fig. 2). Similarly, therefore, the diameter of a well-defined picture of the sun must be 108th part of that picture’s distance

from the opening; and for a hazy picture the size of the aperture in the foliage must be added. Intercept a weak, clearly defined sun-picture on a sheet of paper, hold it perpendicular to the rays of light, measure the diameter

F

IG. 2. We see the sun’s disc at an angle of

radian.

k of the light-spot, and determine by means of a piece of string the distance L from the paper to the opening in the foliage. Is

k really equal to about

?

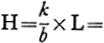

If the sun-pictures formed on a level surface are ellipses, we measure the short axis

k and the long axis

b; the ratio between them equals that between the height H of the tree and the distance L. It follows, therefore, that

. In this way the axes of a strikingly large sun-picture formed by the foliage of a beech-tree were found to measure 21 inches and 13 inches; the height of the aperture from the ground was, therefore, 870 inches or 72 feet 6 inches.

Observe that the sun-pictures are more oblong in the morning and evening, and rounder about noon.

Good sun-pictures are to be found in the shade of beeches, lime-trees and sycamores, but seldom in that of poplars, elms and plane-trees.

Look at the sun-pictures formed by the trees on the banks of shallow water; they can be seen very curiously defined on the bed of the water.

2. Shadows

Look at your own shadow on the ground; the shadow of your feet is sharp, the shadow of your head is not. The shadow of the bottom part of a tree-trunk or post is sharp, whilst the shadow of the higher parts becomes more and more hazy towards the top.

Hold your hand open in front of a piece of paper; the shadow is sharp. Hold it further away; the umbra of each finger becomes narrower and narrower, while the penumbras grow larger until they merge into one another.

These peculiarities are likewise a consequence of the sun’s not being a mere point, and correspond to what the sun-pictures showed us. Look at the shadow of a butterfly, of a bird (how seldom we usually notice such things !) and you will notice that it looks like a round spot; it is a ‘sun-shadow-picture.’

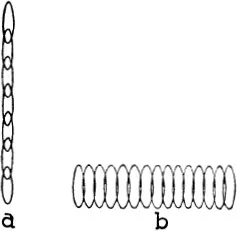

The shadow of wire-netting used as a fence, consisting of rectangular meshes, struck me once as very odd, for only the shadows of the vertical wires were visible, and not those of the horizontal ones ! If a sheet of perforated paper is held in the rays of the sun, each hole in the paper is seen to form an elliptical light-spot on the ground; one can imagine the shadow of a wire to be due to a number of similar small ellipses, only dark this time, placed close together, which makes it fairly sharp when the wire lies in the direction of the longer axis, and indistinct in the direction of the shorter axis (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3. Shadows of iron wires in slanting rays of the sun. (a) Distinct shadow, (b) Indistinct shadow.

Hold a piece of paper immediately behind the wire-netting, then take it farther and farther away, so that the gradual appearance of the remarkable shadows can be followed. Investigate similar cases where the sun’s rays make different angles with the ground: examine also the shadows of slanting meshes, etc.

Shadows have played an important part in folklore. It used to be considered a terrible punishment for anyone to lose his shadow, and anyone possessing a headless shadow would die within a year ! Tales like these, which are told by all peoples at all times are interesting to us, too, as they prove how cautious one should be in believing the assertions of untrained observers, however numerous and unanimous they may be.

3. Sun-Pictures and Shadows during Eclipses and at Sunset

During an eclipse the dark moon is seen to glide in front of the sun’s disc, so that, after a short time, only a crescent remains visible. It is worth while to notice at that moment the resemblance of small sun-pictures underneath the foliage to diminutive crescents, all lying in the same direction, large or small, bright or dim.

The shape of the shadows is influenced in a similar way. The shadows of our fingers, for instance, are peculiarly claw-shaped. Every small, dark object would at such a time cast a crescent-shaped shadow; the shadow of a small rod consists of a number of similar crescents, the curvature appearing at the end.

A good example of an isolated dark object of this kind is a balloon, and indeed it has been noticed that during eclipses of the sun the shadow of both balloon and basket are crescent-shaped. An aeroplane, if high enough, casts a curved shadow, too.

Eclipses of the sun, even partial ones, occur rarely; but similar shadow formations can also be seen while the sun is setting over the sea behind an open horizon, if you study the shadows of coins and discs of different sizes stuck on the window-pane, or hung on a piece of wire. The shape and the distribution of light vary according to the size of the coins, and also as the sun’s disc sinks below the horizon.

4. Doubled Shadows

When the trees have lost their leaves, we often see the shadows of two parallel branches superposed upon each other. A branch quite near to us gives a sharp and dark shadow, one more distant gives a broader and more greyish shadow. The curious thing now is that, when they accidentally fall one upon the other, we see a bright line in the middle of the sharpest shadow, so that this looks double (Fig. 4). What can be the explanation?

Let us suppose that the distant branch looks thicker, the nearer branch thinner. In order to find how strong is the illumin...