![]()

1. What Is the Innovation Paradox?

NOKIA WAS A FINE-TUNED MACHINE when it came to grabbing the latest trends in mobile phone use and translating them into robust, profitable designs. Its scouters mixed up with young urban trendsetters, executives, and families, almost to the point where they understood their customers better than they understood themselves. Techniques ranging from in-depth ethnographies to early prototyping helped the company keep its healthy lead in mobile communication. For instance, the discovery that people in countries such as Morocco and Ghana would share phone conversations led Nokia to develop phones with more powerful speakers, making it easier for more people to participate in conversations.1 Incremental innovations—gradual, regular improvements to existing products and services—allowed Nokia to maintain and extend their lead in the market as they knew it. What could possibly go wrong?

Nokia’s market lead fell apart when the smart phone became the mobile device of choice. Since the company was so successful in the market for traditional mobile phones, when the market shifted away from their flagship products, Nokia was left with a nearly perfect organization innovating for a market whose relevance quickly eroded. Not only did Nokia lose its venerable market position, but it also lost any meaningful chance of making a dent in the smart phone market, allowing companies like Apple and Samsung to establish themselves.

Another example of creative destruction caused by breakthrough innovation—the kind of innovation that disrupts old markets and creates new ones—in the mobile communication industry is the ups and downs experienced by RIM (Research in Motion), the company behind the Blackberry. Blackberry was one of the early winners of the smart phone revolution, with a 22 percent market share in 2009. Executives praised its design and its security. Businessweek ranked it as the eighth most innovative company in the world. But by 2013, users were leaving Blackberry for new devices with more appealing features, and RIM’s market share whittled down to 2.7 percent.2 RIM kept executing on a strategy that had proven to be very successful, but one that had become obsolete in the fast-changing market.

The innovation paradox occurs when the aggressive pursuit of operational excellence and incremental innovation crowds out the possibility of creating breakthrough innovations. Its opposite is also often true—companies with a focus on developing breakthroughs can lose their starting-line position to companies that simply execute better. What happened to Nokia with the advent of the smart phone, and RIM with the growing popularity of touch screens and other smart phone features, are merely two of many examples of companies that have fallen victim to the innovation paradox.

Operational excellence and incremental innovation feed success within existing business models, but they can feed failure when it comes to creating new ones. The financial performance of incumbents frequently deteriorates quickly after an industry goes through a structural change. As Nokia and RIM discovered, by the time the structural change erodes the financial performance of incumbents, it is often too late for the leaders of the old market to catch up. Incremental innovation delivers results as long as the industry structure remains stable, yet it can fail miserably when breakthroughs redefine an industry.

Disruptive technologies and innovations cause drastic market changes.3 The interesting thing is that incumbents often see them coming but then disregard them, to focus on incremental innovation. Nokia, for example, actually had a prototype of a smart phone. Yet their existing customers—the ones the company already knew and understood—were not asking for it. But if you simply ask people what they want, oftentimes the answer will be more of the same; consumers will often extrapolate from whatever is available today. Nokia was extremely successful with the phones they were selling, so why should they introduce a product their customers didn’t even know they wanted? Hence, Nokia kept making improvements on models their customers liked. All the while a new market was about to form, taking with it many of those customers.4

Established companies can choose to disrupt markets through breakthrough innovation, or they can wait and hope: hope that their industries will not radically change, and that incremental innovation will keep on driving success. They can hope that the change will not be too abrupt and that they will be able to catch up; they can hope the change will only be a passing fad; they can lobby to stop the change; or they can be out in front and create the change.5

Operational excellence and incremental innovation succeed as long as an industry follows the predicted path.

All industries experience breakthrough changes that make existing strategies obsolete. At these points, what made companies great can become their largest liability.

INCREMENTAL AND BREAKTHROUGH INNOVATION

Innovation is often mistakenly seen as a singular concept. Either your company is innovative, or it is not; either it’s in your culture, or it’s not. But innovation can best be understood as a range of types and intensities. At the ends of the spectrum are two markedly different phenomena—incremental innovation and breakthrough innovation (figure 1.1). Both have the goal of moving creativity to market, but similarities end soon after that.

Innovation is not a single concept. Failing to capture the differences in types of innovation throughout the management process leads to problems and frustrations.

Incremental innovation is about improvements, while breakthrough innovation is about discovery. Managers looking for the single best way to handle innovation are set to fail. As they search for the golden solution, they become frustrated when their innovation model fails to deliver the expected results. They conclude that their company does not have the culture and resources to achieve the feats they see in other organizations.

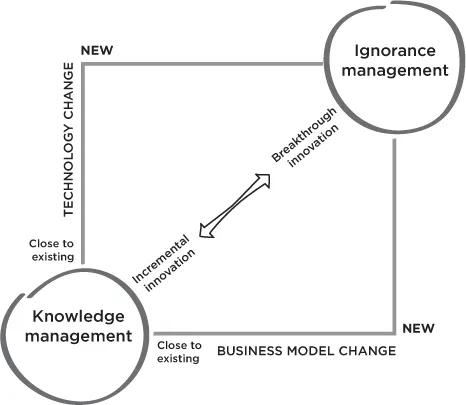

Incremental and breakthrough innovation (and all the shades in between) can be visualized as coming from a range of technology and business models, some existing and others yet to be imagined (see figure 1.2).7 Innovation works best when technological and business model dimensions are brought together. For example, the leadership of fashion firms often pair a creative mind—to come up with concepts that people had never considered—with a business mind—to bring those concepts to the market. Desigual, a fast-growing fashion firm, joined the creativity of Thomas Meyer with the business acumen of Manel Adell. Legendary design firms such as Christian Dior, Ralph Lauren, Prada, and Gucci also combine the separate talents of designers and businesspeople.8

Figure 1.1. Types of innovation

Figure 1.2. The innovation matrix6

Managing incremental innovation is about managing knowledge. Incremental innovation moves the current strategy forward. For instance, when Honda designs its new Odyssey, it isn’t reinventing the automobile. Instead, a new version of an older model likely includes a nice set of novelties. Its safety features are better, its technology makes driving easier, and its entertainment capabilities are enhanced, but most of the parameters that define the car are unchanged.

In contrast, managing breakthrough innovation is about managing ignorance and uncertainties. For instance, consider the questions surrounding the driverless car: Which technology works best? How will people use it? How will it be commercialized? Will it coexist with or replace traditional cars? Will we need garages? How will traffic be regulated on driverless roads? As innovation efforts move away from existing products and services toward new technologies and new business models, uncertainty increases, risk goes up, and knowledge is sparser.

Breakthrough innovation deals with much higher levels of uncertainty and risk, and lower levels of knowledge. Thus, it needs to be managed differently from incremental innovation.

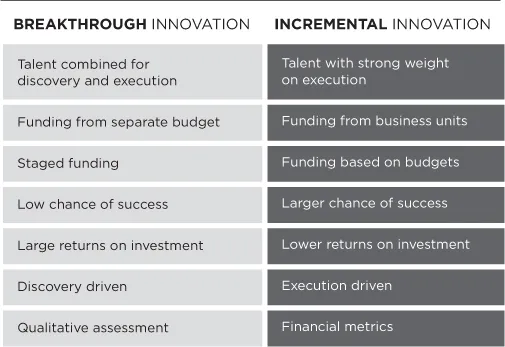

The two extremes of innovation are so different that they can’t be managed the same way, and how you manage determines what you get.9 If what begins as breakthrough innovation is managed as incremental, more likely than not it will become an incremental innovation. Sure, luck plays a substantial role, and a company may be lucky and get a breakthrough from an incremental innovation process. But putting more and more money into traditional incremental innovation processes will probably not significantly increase the already small odds of getting a breakthrough. Table 1.1 describes the main differences between incremental and breakthrough innovation.

Incremental Innovation

Most companies are good at developing innovations that build upon and advance the current strategy—innovations that fit within existing technologies and business models. Such developments help create operational excellence. A large percentage of investments go to feed this sort of innovation, the kind that keeps an organization in the game and gives it an edge over competitors. It is a hugely important type of innovation. Moreover, little steps, if they are taken faster than the pace of competitors, can put a company in the leadership position.

Winning in established markets requires executing faster through incremental innovation cycles. Even in maturing markets, the end-winner is the company able to better execute. Fast seconds—companies that come from behind to dominate markets—often end up at the top of the game.10 Apple largely created the market for smart phones and tablets through the iPhoneiPad revolution, but Google and Samsung have been claiming territory with relentless efforts to bring incremental concepts to market. Pioneers such as Sixdegrees and MySpace explored social media early on, only to see Facebook take the lion’s share of the market, LinkedIn succeed in professional networks, and Twitter take the short communication space.

Table 1.1. comparing incremental and breakthrough innovation

Incremental innovation operates with relatively low amounts of uncertainty, large amounts of knowledge, and often large amounts of resources as well. It benefits from structured processes, because processes are good at managing knowledge and resources efficiently. For example, Logitech has dominated the computer peripheral market for more than a decade now. Every year, they come up with mice, keyboards, and web cams that are better than earlier versions. When Logitech goes into designing these new products, it already knows what the majority of these products will look like. It knows when the new products have to be on the market, the technologies that will go into them, their price points, their features, and a quite accurate development budget estimate. Of course, some uncertainties exist—like whether the new design will appeal to the consumer, or the new features will be better than those of competitors. But these uncertainties pale in comparison to the uncertainties of building industries around “not-yet” markets, like space tourism, nanorobots, or an ageless society.

Incremental innovation is extremely important for sustaining competitive advantage in current markets, and its inspiration benefits mostly from in-depth customer knowledge. Back in early 2000, Logitech, the leader in computer peripherals, had no presence in the keyboard market. One of its marketing department studies asked consumers to name the most important keyboard manufacturers, and even though Logitech had never made a keyboard, it came out as number three on the survey. A lot of companies would discard this information, or discount it as showing how ignorant consumers are—after all, Logitech knew that it had never sold a keyboard. Instead, the company interpreted it as a clear message to get into the market. In the minds of consumers, Logitech built and designed great mice, so they should also make great keyboards. Since keyboards use existing technology and were manufactured and distributed through the same channels as mice, Logitech’s innovation was far from break-through. Yet it became a large and profitable business, and Logitech eventually ended up grabbing the number-one position.

Incremental innovation also benefits from going beyond customer needs into customer motivations. Design thinking and human-centered design effectively use careful observation and patient efforts to determine what people need and why people behave the way they do. They help understand that products not only fulfill a function but also have social and emotional meanings.

Incremental innovation operates with relatively low levels of uncertainty, benefits from established processes, and is extremely important for sustaining competitive advantage in current markets.

Overall, incremental innovation is a fundamental aspect of winning—it can result in rapid improvements for customers as well as for the organization, and it can keep company morale up by maintaining momentum. In fact, incremental innovation is central for staying competitive in current markets, and for defending new developments. While incremental innovation has barriers to achievement, the other end of the spectrum of intensity—breakthrough innovation—is a whole different beast altogether.

Breakthrough Innovation

In 1926, Henry Ford designed an airplane for the mass market—his idea being that everybody would fly an airplane much like they drove a car. The idea of personal planes is still appealing, and various research groups today are working to make this idea a reality. Should these groups successfully design the product and the business model to make it available to a large number of consumers, a lot of the infrastructure that we take for granted will be questioned, and additional infrastructure will need to be creat...