eBook - ePub

The Battle

Alessandro Barbero

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Battle

Alessandro Barbero

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

At Waterloo, some 70,000 men under Napoleon and an equal number under Wellington faced one another in a titanic battle. Alessandro Barbero's majestic account combines British and French histories to give voice to all nationions involved. The Battle is a masterpiece of military history.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Battle un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Battle de Alessandro Barbero en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Historia y Historia del mundo. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

HistoriaCategoría

Historia del mundoCONTENTS

Illustrations

Campaign Maps

Prologue

PART ONE – “We’ll See Tomorrow”

1. The Night Before

2. “Who Will Attack the First Tomorrow?”

3. “The Decisive Moment of the Century”

4. The Nature of the Armies

5. The British Army: “The Scum of the Earth”

6. The French Army: “All Must March”

7. The Prussian Army

8. The Minor Armies

9. “As Bad a Night as I Ever Witnessed”

10. On the Brussels Road

11. Letters in the Night

PART TWO – “It Will Be as Easy as Having Breakfast”

12. “Very Few of Us Will Live to See the Close of This Day”

13. The Emperor’s Breakfast

14. The Numbers in the Field

15. Wellington’s Deployment

16. Napoleon’s Deployment

17. “Vive l’Empereur!”

18. What Is a Battle?

19. Napoleon’s Orders

20. Napoleonic Infantry Tactics

21. The Skirmish Line

22. Hougoumont

23. The Defence of the Château

24. The Bombardment in the Hougoumont Sector

25. The Attack on the North Gate

26. The Grande Batterie

27. News of the Prussians

28. Bülow’s March

29. New Orders for Grouchy

30. La Haye Sainte

31. The First Attack on La Haye Sainte

32. Crabbé’s Charge

33. D’Erlon’s Advance

34. The Attack on the Sunken Lane

35. The Firefight Along the Chemin d’Ohain

36. The Intervention of the British Cavalry

37. The Charge of the Household Brigade

38. The Charge of the Union Brigade

39. Dragoons Against Guns

40. Jacquinot’s Lancers

41. “Tu N’es Pas Mort, Coquin?”

PART THREE – “A Stand-up Fight between Two Pugilists”

42. “It Does Indeed Look Very Bad”

43. Papelotte

44. The Second Attack on La Haye Sainte

45. The Great French Cavalry Attacks against the Allied Squares

46. “Where Are the Cavalry?”

47. “Vous Verrez Bientôt Sa Force, Messieurs”

48. Blücher Attacks

49. Plancenoit

50. “I’ll Be Damned If We Shan’t Lose This Ground”

51. The Nivelles Road

52. “Infantry! And Where Do You Expect Me to Find Infantry?”

53. The Last Effort to Take Hougoumont

54. The Capture of La Haye Sainte

55. The Advance of the French Artillery

56. The Renewed Attack on Plancenoit

57. Ziethen at Smohain

58. Napoleon’s Last Attack

59. “Voilà Grouchy!”

60. The Imperial Guard’s Advance

61. The Attack of the Imperial Guard Grenadiers

62. “La Garde Recule!”

PART FOUR – “Victory! Victory!”

63. The Allied Advance

64. The Squares of the Old Guard

65. The Meeting at La Belle Alliance

66. The Prussian Pursuit

67. Night on the Battlefield

68. “A Mass of Dead Bodies”

69. Letters Home

70. “I Never Wish to See Another Battle”

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Index

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

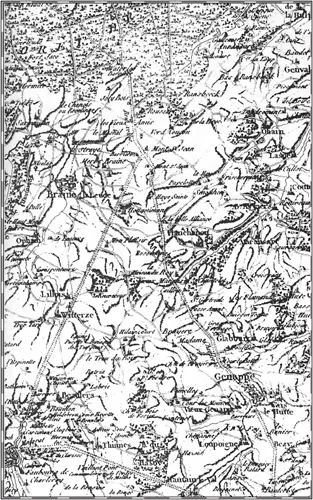

Detail of a Ferraris & Capitaine map of 1797

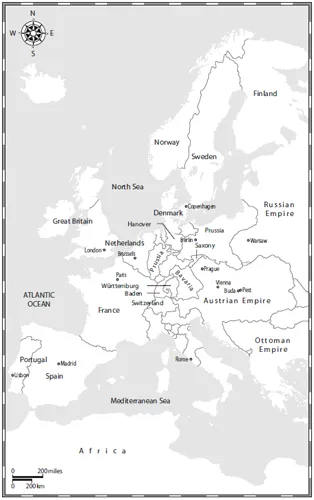

Europe in 1815

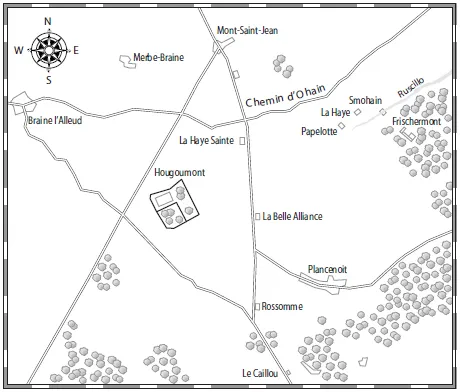

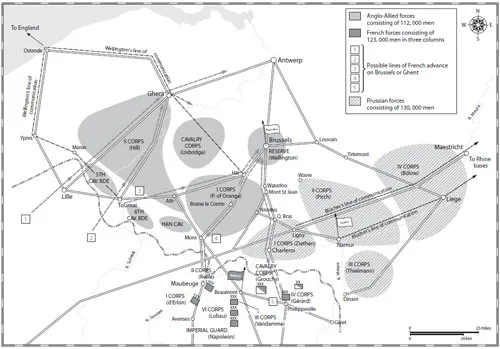

Overview of the Battle Area

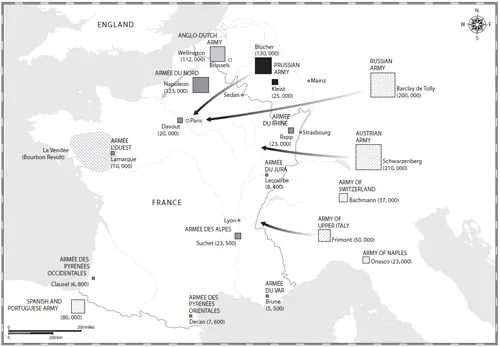

Allied Advances in June/July 1815

Deployment of French Troops

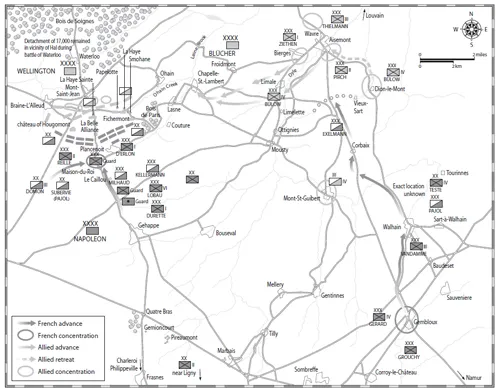

Battle of Waterloo, 10.00hrs, 18 June 1815

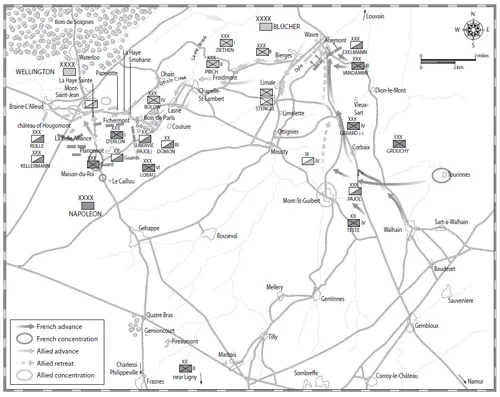

Battle of Waterloo, 16.00hrs

PLATES

Napoleon Bonaparte. Painting by Robert Lefèvre. (Wellington Museum, London)

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, 1814. Painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence. (The Art Archive/Wellington Museum London/Eileen Tweedy)

The elderly Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. (The Art Archive/Wellington Museum London/Eileen Tweedy)

Napoleon giving orders to an aide-de-camp for Marshal Grouchy on the morning of the battle. (The Art Archive)

General Reille, commander of Napoleon’s II Corps. Engraving by A. Tardieu. (Collection Viollet)

Jérome Bonaparte, division commander and Napoleon’s youngest brother. Painting, 1808. (The Art Archive/Musée du Château de Versailles/Dagli Otti)

The Duke of Wellington outside his headquarters at Mont-Saint-Jean. Painting by J. C. Aylward. (The Art Archive/Eileen Tweedy)

The ceremonial Eagle, mounted on a pole with the French tricolour. (Collection Viollet)

A 12-pounder gun, one of les belles filles de l’Empereur. (Mark Adkin)

Crops of rye in June. (Mark Adkin)

British soldiers form a square to defend against cavalry attacks. (Mary Evans)

The Guards brigade attack the French to alleviate the pressure on the defenders of the château, just visible in the far right background. Painting by Denis Dighton. (Bridgeman)

The French bombard Hougoumont, prompting the British artillery to open fire, against Wellington’s orders. (Mary Evans)

General von Bülow. German engraving. (Bridgeman)

Marshal Grouchy. Engraving. (The Art Archive/Musée Carnavelet Paris/Dagli Orti)

The battle around the farmhouse and stables at La Haye Sainte. Painting by R. Knotel. (Mary Evans)

Count d’Erlon holding his marshal’s baton. Engraving by Collier after Larivière. (Collection Viollet)

“That old rogue,” Sir Thomas Picton. (Mary Evans)

The charge of the Scots Greys. Painting by Lady Butler. (Mary Evans)

Marshal Ney. (Mary Evans)

French cuirassiers charging a Highlanders’ square. Painting by Félix Philippoteaux, 1874. (The Art Archive/Victoria & Albert Museum/Eileen Tweedy)

Colonel von Ompteda. (National Army Museum)

Nassauers defending their position at La Belle Alliance. Painting by R. Knotel. (Mary Evans)

Blücher orders his men to attack Plancenoit. Painting by Adolf Northern. (Bridgeman)

An officer of the mounted chasseurs of the Imperial Guard. Painting by Gericault. (Mary Evans)

Napoleon, viewing the attack on his Imperial Guards through a spyglass. Painting by James Atkinson. (The Art Archive)

Colonel Hew Halkett captures the French general Cambronne. Painting by R. Knotel. (Mary Evans)

Wellington signalling the general British advance on Waterloo. Painting by James Atkinson. (The Art Archive/The British Museum)

The Earl of Uxbridge, commander of the Allied cavalry. Painting by Peter Edward Stroehling, c. 1816. (National Army Museum)

The surgeon’s saw used to amputate Lord Uxbridge’s leg. (National Army Museum)

The famous meeting between Wellington and Blücher, depicted here in front of the inn at La Belle Alliance. (Mary Evans)

General von Gneisenau. (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Napoleon among his men as he faces defeat. His carriage awaits his flight. Painting by Ernest Crofts. (Mary Evans)

Napoleon Bonaparte burning the eagles and standards of his Imperial Guard after the battle. (The Art Archive)

A burial party at work near La Belle Alliance, seven days after the battle. Engraving by E. Walsh, drawn on the spot. (Mary Evans)

British soldiers removing French cannons, July 1815. (Collections Viollet/Bibliothèque Nationale)

Detail of a Ferraris & Capitaine map of 1797, as used by Napoleon and on which Wellington’s own map was based.

Europe in 1815

Overview of the Battle Area

Allied Advances in June/July 1815

Deployment of French troops

Battle of Waterloo, 10.00hrs, 18 June 1815

Battle of Waterloo, 16.00hrs, 18 June 1815

THE BATTLE

PROLOGUE

In the afternoon of 1 March, 1815, a fleet consisting of one warship and six smaller vessels dropped anchor off Golfe-Juan on the southeastern coast of France, in view of what are today the most luxurious vacation spots on the Côte d’Azur but what were then miserable fishing villages clinging to the edge of an inhospitable landscape. As soon as they were anchored, the ships lowered their small boats. Shortly thereafter squads of soldiers began to disembark on the shore, despite the protests of the flabbergasted customs official who had rushed to the scene to contest this highly irregular landing. The first troops to reach solid ground went to knock on the gates of the nearby French fort at Antibes and were immediately placed under arrest; but the small boats kept bringing ashore other soldiers, and soon more than a thousand grenadiers had been disembarked, along with two cannon and an entire squadron of lancers who spoke Polish among themselves. Finally, towards evening, the leader of this host came ashore in person, walking over an improvised gangway, which his men, standing in water to their waists, held up for him; and an officer was sent to notify the commandant of the fort that the emperor Napoleon, after ten months of exile on the island of Elba, had returned to France to reclaim his throne.

Even in an age without the benefit of mass media, the news of Napoleon’s return was so astonishing that it travelled throughout the continent in a few days, arousing consternation or enthusiasm everywhere. Europe had really believed that the Napoleonic Wars were over, and with them the French Revolution, which together had inflamed the world for twenty-five years. Kings had regained possession of their thrones, armies had been demobilized, and a cosmopolitan, self-satisfied political class was preparing for the tranquil task of managing a long period of peace. The fact that Napoleon was still alive, exiled to an island somewhere in the Mediterranean Sea, was certainly irritating, but people tried hard not to think about it. When the Duke of Wellington announced to the Congress of Vienna – where, since Napoleon’s abdication, representatives of the European powers were leisurely redrawing the political map of Europe – that the exile had escaped from Elba and landed in France, the delegates burst into laughter, believing that the announcement was some sort of joke. A few days sufficed to change their minds: on 13 March, the Congress published a resolution, couched in the diplomatic French of the period, in which Napoleon was proclaimed an outlaw, subject to “vindicte publique”, whereupon the English Parliament and half the chancelleries of Europe began discussions to decide whether this formula meant that anyone could kill him with impunity, or whether it would first be necessary to arrest him and put him on trial.

Meanwhile, on 20 March, the emperor made a triumphant entry into Paris, while King Louis XVIII and the whole Bourbon family fled hurriedly to Belgium. From there he sent personal letters to all the sovereigns of Europe, assuring them in the most modest tones that he desired only peace and that he renounced all claims whatsoever to any of the territories that previously, at the apogee of his empire, had belonged to France. But the European chancelleries did not deign to respond to these missives; in London, the prime minister would not even permit the prince regent to open the letter and had it returned with its seal intact. One year earlier, four great powers – England, Austria, Russia, and Prussia – had combined to defeat Napoleon; now, on 25 March, 1815, the same four countries signed a treaty in which each of them pledged to put an army of 150,000 men into the field as soon as possible, with the set purpose of invading France from all sides. England, then the dominant economic power in the world, agreed to finance the mobilization of the Allies, and the Rothschild bank began gathering quantities of cash, eventually furnishing His Majesty’s government with the immense sum of 6 million pounds sterling, which corresponded to the estimated total cost of the undertaking.

In these circumstances, Napoleon’s only recourse was to rearm, and he did so with all his extraordinary talent for organization, a talent that the passage of time had not diminished. The army he inherited from the Bourbons was brought back up to full strength, the previous year’s conscripts were recalled, the National Guard was mobilized, the mass production of muskets began, and all available horses were either bought or confiscated; as a result, French treasury reserves were consumed within a few weeks, and financing had to be extorted from reluctant banks. Even with their help, however, the emperor could not hope to be successful in opposing the four armies that were about to invade France; he had tried to accomplish such a feat a year before, when his resources were decidedly more extensive, and things had not turned out well for him. His only hope was to beat his opponents to the punch.

Even though the training period for new conscripts could be reduced, in times of emergency, to a few weeks, the armies of the day still required several months to equip their forces properly and put themselves on a war footing. As spring drew to an end, only two o...