![]()

part one

What is myth?

![]()

Section A: What is myth?

Locating the field

It is necessary for a systematic exploration of the various approaches that constitute the academic study of myth to begin with a clear sense of the scope and limits of the category of mythology. What may seem like a simple (and even) trivial task is both highly challenging and rewarding, not least because of the vast array of definitions and understandings that exist. Myth is clearly a story of some sort, but most people would not be happy with the idea that all stories are myths. What is more, when we ask the question of myth’s nature, we inevitably come to the consideration of how myth relates to other types of narratives, such as legend and the folktale. One possible dividing line between myth and other narratives is that of truth. While for many myth is a story that is false, others have taken the opposing view, defining myth as a story that is true, venerable and (even) sacred (cf Bascom 1965: 9). This, in turn, leads to the question of what is meant by truth, in particular the nature of the truth that is to be conveyed (natural, social or psychological). The texts in this section all grapple with this question in their own way, and they each move towards the development of a distinct (yet clear) concept of myth.

C. Scott Littleton’s ‘A Two-Dimensional Scheme for the Classification of Narratives’ differentiates myth from other material on precisely the grounds of its veracity and its secularity (true/false: sacred/secular). Our second reading for this section, which is a piece by Ben-Amos, complicates this sketch. Here, Daniel Ben-Amos draws on his background as a folklorist to offer a strongly argued conception of mythology in relation to folklore. This centres on the universality of folklore and its existence as a broad-based, yet distinct form of narrative. Finally, Malinowski’s Myth in Primitive Psychology utilizes his understanding of myth as it is contextually employed to reveal the relationship of myth to social systems. He neatly demonstrates how myth’s truth can be found in the way that it relates to the ideal social order of those who tell the narrative. Malinowski also opens the exploration of the contingency of myth’s truth, which is shown to rest upon both who tells the myth and the context of the telling. Collectively, these readings introduce distinct, yet equally influential, ways of delimiting the field of study. In so doing, they provide a firm foundation for the later sections of this Reader, where we will often find ourselves drawn back to these core definitions.

Reference

Bascom, W. (1965). ‘The Forms of Folklore: Prose Narratives’. The Journal of American Folklore 78 (307): 3–20.

![]()

1

A two-dimensional scheme for the classification of narratives

C. Scott Littleton

Covington Scott Littleton (1933–2010) was an American anthropologist. He was born in Los Angeles and spent most of his life in and around the city. He obtained BA, MA and PhD degrees from the University of California, Los Angeles, before working at Occidental College, United States. At Occidental, he was Professor of Anthropology and served as the chairman of first the combined sociology and anthropology department and then the (newly independent) anthropology department. Littleton’s research, throughout his career, focussed primarily on the exploration of mythology and folklore, especially the King Arthur legends. Later in his career, he turned increasingly towards exploring the occult and UFO phenomenon, spurred by an increasing desire to understand a strange personal sighting of a UFO. In this chapter, Littleton develops his famous two-dimensional scheme for the classification of narratives (including folklore, legend and myth). This leads Littleton to seek a universal classification for mythology that helps to distinguish it from other forms of narrative. In so doing, Littleton taps into wider concerns about both the veracity and the sacrality of narrative.

Even the most cursory examination of the wide and diverse range of terms that have been used by anthropologists, folklorists, mythologists, and others to refer to various categories of folk literature will reveal a terminological confusion second to none in the social sciences. One man’s myth is all too often another man’s legend; what to one scholar is manifestly an example of ‘lower mythology’ is to another simply a folk tale or Märchen. Rarely indeed does one find a clear-cut statement as to the key differences between the terms utilized.

Yet closer inspection of the many definitions of myth, folktale, Märchen, legend, saga, epic, and the rest of the sometimes bewildering array of terms which since the days of Euhemerus have been coined to refer to various types of folk narratives does in fact reveal some common denominators. If one analyzes the classic nineteenth- and twentieth-century definitions and usages of the terms in question, from Max Müller to Malinowski, from Hartland and Lang to Thompson and Bidney, it becomes clear that two basic criteria are almost always applied, more often than not implicitly, in the categorization of narratives or tales – regardless of the specific terms or labels used. These are (1) the extent to which a narrative is or is not based upon objectively determinable facts or scientifically acceptable hypotheses, and (2) the extent to which it does or does not express ideas that are central to the magico-religious beliefs and ideology of the people who tell it. It is the purpose of this paper to bring these fundamental criteria to light and to suggest in terms of them a tentative two-dimensional classificatory scheme.

The first criterion, that which relates to the relative degree to which a narrative is grounded in fact or fancy, has perhaps best been expressed by Bidney in his assertion that ‘Myth originates wherever thought and imagination are employed uncritically or deliberately used to promote social delusion.’1 In this use of the term myth Bidney thus implicitly distinguishes between two broad categories of narratives: those that are grounded in fact or rationality and those that are not (such as myths, folk tales). The second criterion, that which relates to what I may term, following Durkheim, Radcliffe-Brown, Redfield, Warner, and others, the relative sacredness or secularity of a narrative, is implicit in almost all modern social anthropological attempts to distinguish between myths and folk tales. Lessa and Vogt, for example, define myths simply as ‘sacred stories.’2

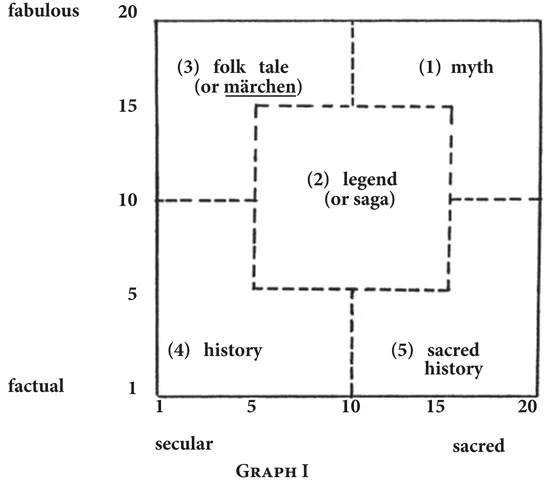

But neither of these two criteria – no matter how rigorously applied – is alone sufficient for the purpose at hand, which is to arrive at meaningful categories of narratives. For it seems to me that such categories can be arrived at only if both are applied, only if each criterion is translated into a dichotomy between two polarities or ideal types: the first criterion, thus, is translated into a dichotomy between absolutely factual (or scientific) and absolutely fabulous (or non-scientific), and the second appears as a dichotomy between absolutely secular and absolutely sacred.3 The result is a two-dimensional scheme which can be expressed graphically (see Graph I).

At this point, however, one fundamental theoretical assumption should be made clear. The dichotomies suggested here are necessarily asymptotic and therefore must be phrased in terms of continua.4 No given narrative will ever completely approximate any one of these several poles or ideal types;5 there is no such thing as a wholly or absolutely sacred or fabulous narrative, nor is there one that is wholly factual or secular. All must fall somewhere in between. A narrative is located on each continuum (or axis) in terms of the degree to which it more closely approximates one or the other of the poles in question – that is, in terms of the degree to which it is more sacred than secular, more fabulous than factual, or vice versa.

It is, of course, difficult to quantify the degree of sacredness or secularity of a narrative, let alone the degree to which it is factual or fabulous; and the rating system is at present still largely based upon rule of thumb. Nevertheless, in order to facilitate comparisons, I have devised a 20-point scale, wherein a score of one is applied to those narratives which seem most closely to approximate, respectively, the factual and secular poles, and a score of 20 is applied to those which most closely approximate, respectively, the fabulous and sacred poles.

As I see it, the scheme yields five major categories. Using traditional labels wherever possible, these are (1) myth, composed of narratives which are extremely sacred and patently fabulous (those narratives which score above 10 on the sacred-secular axis and above 15 on the factual-fabulous axis, or vice versa); (2) legend (or saga), composed of narratives which are relatively sacred and fabulous (those which score between 5 and 15 on both axes); (3) folktale (or Märchen), composed of relatively secular albeit fabulous narratives (those which score below 10 on the sacred-secular axis and between 15 and 20 on the factual-fabulous axis, or below 5 on the sacred-secular axis and above 10 on the factual-fabulous axis); (4) history, composed of relatively secular and factual narratives (those which score below 10 on the sacred-secular axis and below 5 on the factual-fabulous axis, or vice versa); and (5) sacred history, composed of narratives which are relatively (or extremely) sacred yet firmly grounded in fact (those which score above 10 on the sacred-secular axis and below 5 on the factual-fabulous axis, or above 15 on the sacred-secular axis and between 5 and 10 on the factual-fabulous axis). The distribution of these five categories, the boundaries between which necessarily overlap to some extent, can be seen in Graph I.

The first category, that of myth, necessarily includes all of those narratives which purport to explain the creation of the universe, of the supernatural beings who direct it, and of the human beings who populate it. It will also include perhaps the majority of those narratives which in an oral tradition function to explain the basic facts of human existence, such as birth, death, storms, floods, fire, and earthquakes. Here, for example, would be located such narrative phenomena as the Greek theogony, Genesis I, the ancient Irish account of the Tuatha de Danann, much of the Elder Edda, especially the Voluspa, the Hawaiian and other Polynesian creation stories, the Babylonian Gilgamesh cycle, and the Rig Vedic account of how Indra released the waters from captivity and thereby permitted the cosmos to assume its present shape.6 In short, the category here labeled myth includes all of those narratives which in the eyes of the tellers are extremely sacred and in the judgement of the investigator are unrelated to historical or scientific facts.

The second category, that of legend or saga, includes those narratives which cluster around the mid-point of the graph: those which have at least a marginal relationship to historic or scientific fact and which are generally more open to rational interpretation by those who tell them. The range here runs from narratives which border on myth or folktale to those which border on history or sacred history. Perhaps the best examples of narratives that fit this category can be found in the ancient epic literatures of the Old World, especially those which concern heroic rather than divine beings. Much (but by no means all) of the Iliad, Mahäbhärata, and Volsung-asaga might be located here, as might the Russian tales of the hero Igor and the Irish accounts of Finn and the fianna.7

The third category, that of folktale or Märchen, includes those narratives which are told primarily for entertainment – though they may well reflect themes also expressed in myths and legends and thus serve to reinforce the didactic functions served by the latter, especially as far as children are concerned – and are indeed open to rational interpretation. Their factual content, however, may be as minimal as that of the most fabulous of myths. It is this sort of ‘popular tales and traditions’ that William Thoms sought to distinguish when he coined the term ‘folk-lore’ in 1846. Examples here are legion in any tradition, in large measure, it would seem, because the relatively secular character of such narratives permits a range of variation and adaptation far wider than that generally present among myths and, to a lesser extent, legends. The folktale, as Stith Thompson8 and others have long since amply demonstrated, is certainly the most easily diffusible category of folk narrative; this again is a reflection of secularity.

The fourth category, history, includes narratives that generally conform to the basic definition of history: a factual and objective record of past events. That such a category of narratives, no matter how minimal, is inevitably present in all folk or oral traditions seems obvious, Lord Raglan and his supporters to the contrary notwithstanding.9 Yet history, whether oral or literate, is never wholly factual or objective (that is, secular), and this is taken into account here. For as I see it, there is no sharp line between history and either myth, folktale, or legend; and a given narrative is here classed as history only if it is indeed more secular than sacred and more factual (in the judgment of the investigator) than fabulous. It is suggested, however, that when applied to an oral tradition this category will probably contain fewer items than any other and that with the passing of a few generations most narratives initially classifiable as history will have moved into the categories of myth, legend, or folktale.

The fifth and last category, that of sacred history, comes close to approximating what a number of theologians and Old Testament scholars have labeled Heilsgeschichte,10 or the idea that in the Old Testament there can be found more or less factual accounts which have nevertheless become fundamental in the development of Judaism. Here again, this is a logical category which will, it seems to me, be present in all traditions, at least to some extent. It includes narratives that are grounded in fact yet at the same time relatively closed to interpretation or analysis on the part of the culture concerned. The lives of Saul, David, and Solomon, as well as those of the later prophets, are examples of sacred history. To a much lesser degree, the American Revolution, the life of Washington, and the careers of Lincoln and Robert E. Lee (at least in Virginia) also fit into this category. Inevitably, only a fraction of what begins as history passes into the category of sacred history. Indeed, the latter category often seems to serve as a halfway house, as it were, between history and myth or legend.

It remains to suggest some of the scheme’s possible applications. In the first place, of course, it could prove useful to one who is concerned with the synchronic analysis of a given narrative tradition, if only as a taxonomic device. A second application would be to comparative studies of two or more contemporary traditions. Each could be plotted and the lie of the points might well yield patterns n...