eBook - ePub

Understanding Behavioral BIA$

A Guide to Improving Financial Decision-Making

David C. Krawczyk, George H. Baxter

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 206 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Behavioral BIA$

A Guide to Improving Financial Decision-Making

David C. Krawczyk, George H. Baxter

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This book describes the biases most relevant to investing, include background on how biases develop, and offer practical strategies to help you to improve your performance.

The authors offer a guide to categorizing biases based on cutting-edge brain science, which will enable readers to implement best practices that guard against whole sets of biases. Emphasis is placed on the practical implications of financial decision-making and provides a scientific basis for adjusting investing practices, to avoid common cognitive traps.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Understanding Behavioral BIA$ un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Understanding Behavioral BIA$ de David C. Krawczyk, George H. Baxter en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Business y Gestione patrimoniale. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

BusinessCategoría

Gestione patrimonialeCHAPTER 1

Our Biased Brains

Heuristics and Biases

A heuristic is often defined as a “rule of thumb,” or mental shortcut. A stop-loss rule is an example of an investing heuristic. Investors can limit their losses at a given price point mitigating the risk that any individual issue may pose to their portfolio. Many investors can recognize when they are on the unfortunate side of a probabilistic determination, or when they face a more significant risk than planned when the price does not reflect their narrative. They then rely on the stop-loss heuristic to overcome the possibility of an undesirable result or analytical misjudgment based on their past experience in similar circumstances.

Biases are tendencies to process some information differently based on the current circumstances. A bias toward certain thoughts or behaviors can emerge for a variety of reasons. Heuristics and biases are related. Heuristics derive from biases that we develop. Most biases emerge over time and they are shaped by our experiences. Biases lead us to act a certain way under certain conditions. Our biases are linked to what we have experienced and our expertise level. An expert in technology investments will hold a variety of biases that are driven by a set of situations that they have seen play out time and again in that industry. As such, the expert can often act with an intuitive sense. By contrast, the novice will need to devote much more time and resources to evaluate appropriate value.

Let’s consider a now famous example, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s representativeness heuristic. Coin flips provide an illustrative example of this bias in action. A sequence of seven heads in a row feels contrived and improbable, while a sequence containing a healthy mix of heads and tails feels more probable. The mixed sequence looks random, as most do, while straight heads seems like a rare circumstance. The coin flip example captures a heuristic that leads people to prioritize their own intuitive feelings over statistics. We know that the probability of a head or tail flip is always 50 percent regardless of the previous number of sequential outcomes, but the run of heads feels different to people. This example illustrates that we judge sequences or situations to be more probable if they look like “good representatives” of the distribution from which they are drawn.

Biases and heuristics can sometimes help us. The expert gets through his day making relatively confident decisions using fast intuitive judgments. Experts become trusted analysts and advisors because they are correct a lot of the time and their bias-driven heuristics come to be appreciated as tools to be rapidly deployed, while less experienced decision makers scramble to understand the basis for unexpected changes.

There is an ominous dark side to heuristics and biases as well. The expert who is driven by biases may be wrong in an important analysis due to careless over-application of his heuristics. We often act on our biases in an intuitive fashion. They feel right. We do not question them. This expediency can lead to errors when more analysis is called for. A heuristic can emerge and steer us astray during a key decision because the surface characteristics of a situation appear to match a well-developed and previously successful tendency. We are wrong some of the time when we follow our biases because we have misread the surface situation. What’s worse, we usually walk right into our own trap when our simplified version of reality differs from what is actually going on.

Biases Emerge from the Limited Information Processing Power of Our Brains

Biases are based on how we make sense of the world using our limited powers of attention, memory, and knowledge. Biases lead us astray when solving thought problems. This is particularly troublesome when we make quantitative estimates. We rely on biases when information is abundant and complex. We also rely on biases when a situation reminds us of something we have seen many times before. In other words, precisely the type of information processing that must be accomplished in investment analysis can lead us to make inappropriate thinking errors based on our biases.

Mental Blind Spots: The Brain’s Behavioral Biases

A key point for investing is that the brain builds an incomplete internal mental model of the outside environment. This incomplete model is also distorted by the particular details to which we attend and those that we miss. When you build a narrative on a company, it will be somewhat distorted, as you can only attend to a subset of the information available. Further, many investors tend to exaggerate the importance of the attended information to the exclusion of the things they missed. Those missing details can turn out to be critical.

The brain is like the proverbial blind men who attempt to describe an elephant as they each examine different parts of the animal by touch (Figure 1.1). Like the different men experiencing sensory differences between the tusks and the skin, our sensory systems take in different parts of the environment. Just like the blind men, the brain misses key aspects of the incoming information and this leaves us with gaps in our understanding. Unlike those arguing men who struggle to agree on the true nature of the animal, our brains generate a mental model of the narrative that feels very real to us. We can think of this as a somewhat incomplete mental sketch of reality. Through filtering and integrating the information, the brain resolves inner conflict and our conscious minds feel as if our narratives are closer to reality than they really are. This is a key part of why cognitive biases persist even after we become aware of their presence.

Figure 1.1 The proverb of the blind men and an elephant. Each man can describe only part of the elephant based on his limited experience

Source: Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.

Knowing about biases may be “half the battle,” but that’s not quite enough to conquer their undue influence. We will also discuss methods that will help you to overcome many of these attention biases through your work, or at least minimize their undue influence on your portfolio outcomes. We will next provide you with some introductory information about the brain that is relevant to understanding how it generates behavioral biases.

and knowing is half the battle

—Roadblock, (G.I. Joe Public Service Announcement)

The Brain: An Overview

Your brain weighs approximately three pounds with much of this mass being made up by its outer layer, the cortex. The cortex is too large to fit around the small surface of the brain, so it is folded into a series of bumps and valleys. Species with small amounts of cortex have smooth brains, while organisms with large amounts of cortex have highly convoluted brains. Small, smooth brains have less processing power and typically generate simpler behavior. Species with large cortical mass include dolphins, elephants, and great apes. Like us, these species lead complex social lives and engage in a sophisticated array of behaviors. They likely possess some degree of consciousness as well. Our cortex has allowed us to develop monetary systems and the ability to mentally simulate the future to make predictions about value.

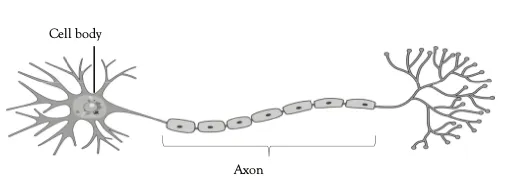

Neurons: the brain’s processing power: Our huge cortex contains billions of electrically active cells called neurons (refer to Figure 1.2). Neurons communicate through an electrochemical process called the action potential. Neurophysiologists commonly refer to action potentials as spikes, in which the neuron moves from a negative polarity state to a positive one and back again in just a fraction of a second. The spikes form the ones and zeros in the brain’s binary code, similar to computer software. Also, like computers, our brains are networked by insulated high-speed connections called axons (Figure 1.2). Bundles of axons form large-scale tracts and these tracts comprise the information superhighways of our brain. Our brains operate by delivering and receiving electrically coded messages, sometimes across long distances within the brain.

Figure 1.2 The structure of a neuron. An electrical action potential is generated within the cell body and transmitted down the axon influencing other connected neurons

Source: Image by Sanu N CC-BY-SA-4.0, from Wikimedia Commons (captions added).

Two types of tissue are most obvious when looking at the brain. The grey matter is made up of binary code generati...