![]()

1

Managing Ahead

We know more about the motives, habits, and most intimate arcana of the primitive people of New Guinea or elsewhere, than we do of the denizens of the executive suites in Unilever House.

Roy Lewis and Rosemary Stewart (1958:17)

A half century has passed since the words above were written, and they still hold true. Yet it is easy enough to find out what managers do. Observe an orchestra conductor, not in performance but during rehearsal, to break through the myth of the manager on a podium. Sit in as the managing director of a high-technology company joins the discussion of a new project. Take a walk with the manager of a refugee camp as he scans attentively for signs of impending violence.

Finding out what managers do is not the problem; interpreting it is. How do we make sense of the vast array of activities that constitute managing?

A half century ago Peter Drucker (1954) put management on the map. Leadership has since pushed it off the map. We are now inundated with stories about the grand successes and even grander failures of the great leaders. But we have yet to come to grips with the simple realities of being a regular manager.

This is a book about managing, pure if not simple. I have given it a broad title, Managing,1 because it is meant to be basic and comprehensive, about this fundamental practice in its untold variety. We consider the characteristics, contents, and varieties of the job, as well as the conundrums faced by managers and how they become effective. My objective is straightforward. Managing is important for anyone affected by its practice, which in our world of organizations means all of us. We need to understand it better, in order for it to be practiced better.

Those befuddled by some or all of this practice—which hardly excludes managers themselves—should be able to reach for a book that provides insights from evidence, comprehensively, on the big questions. Few books even try; this one does. It addresses questions such as these:

• Are managers too busy managing to contemplate the meaning of management?

• Are leaders really more important than managers?

• Why is so much managing so frenetic? And is the Internet making this better or worse?

• Is the whole question of management style overrated?

• How are managers to connect when the very nature of their job disconnects them from what they are managing?

• Where has all the judgment gone?

• How is anyone in this job to remain confident without becoming arrogant? Or to keep success from becoming failure?

• Should managing be restricted to managers?

Whatever Happened to Managing?

I began my career on this subject: for my doctoral thesis, I observed one week in the working life of five chief executives. This led to a book called The Nature of Managerial Work (1973) and an article called “The Manager’s Job: Folklore and Fact” (1975). Both were well received. My research also led to a stream of replication studies.2

But that stream died out, and today we find remarkably little systematic study of managing. Many books are labeled “management,” but not much of their contents are about managing (Brunsson 2007:7; Hales 1999:339).3 Look for the best evidence-based books on the subject, and you will likely settle on Len Sayles’s Leadership: What Effective Managers Really Do and How They Do It (1979), John Kotter’s The General Managers (1982), Robert Quinn et al.’s Becoming a Master Manager (1990), and Linda Hill’s Becoming a Manager (first edition, 1992). Notice the dates.

As a consequence, our understanding of managing has not advanced. In 1916, the French industrialist Henri Fayol published General and Industrial Administration (English translation, 1949), in which he described managing as “planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating, and controlling.” Eighty years later, a Montreal newspaper reported the job description of the city’s new director-general: “responsible for planning, organizing, directing, and controlling all city activities” (Lalonde 1977:1). So remains our prevalent understanding as well.

For years I have been asking groups of people in this job, “What happened the day you became a manager?” The response is almost always the same: puzzled looks, then shrugs, and finally comments such as “Nothing.” You are supposed to figure it out for yourself, like sex, I suppose, usually with equivalently dire initial consequences. Yesterday you were playing the flute or doing surgery; today you find yourself managing people who are doing these things. Everything has changed. Yet you are on your own, confused. “The new managers learned through experience what it meant to be a manager” (Hill, second edition, 2003:9).

Accordingly, in this book I revisit the nature of managerial work, retaining some of my earlier conclusions (in Chapter 2), reconceiving others (in Chapters 3 and 4), and introducing new ones (in Chapters 5 and 6).

Some Sobering Reality

• Because he was Sales Manager for Global Computing and Electronics at BT in the U.K., you might have expected Alan Whelan to have been meeting customers, or at least working with his people to help them sell to customers. On this day, Alan was selling, all right, but to an executive of his own company, who was reluctant to sign off on his biggest contract. Was Alan planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating, or controlling?

• “Top” managers take the long view, see the “big picture”; “lower”-level managers deal with the narrower, immediate things. So why was Gord Irwin, Front County Manager of the Banff National Park, so concerned with the environmental consequences of a parking lot expansion at a ski hill, while back in Ottawa, Norman Inkster, Superintendent of the whole Royal Canadian Mounted Police, was watching clips of last night’s television news to head off embarrassing questions to his minister in Parliament that day?

• And why was Jacques Benz, Director-General of GSI, a high-technology company in Paris, sitting in on a meeting about a customer’s project? He was a senior manager, after all. Shouldn’t he have been back in his office developing grand strategies? Paul Gilding, Executive Director of Greenpeace International, was trying to do just that, with considerable frustration. Who had it right?

• Fabienne Lavoie, Head Nurse on 4 Northwest, a pre- and postoperation surgical ward in a Montreal hospital, was working from 7:20 A.M. to 6:45 P.M. at a pace that exhausted her observer. At one point, in the space of a few minutes, she was discussing a dressing with a surgeon, putting through a patient’s hospital card, rearranging her scheduling board, speaking with someone in reception, checking on a patient who had a fever, calling to fill in a vacancy, discussing some medication, and chatting with a patient’s relative. Is managing supposed to be that hectic?

• Finally, what about the famous metaphor of the manager as orchestra conductor, magnificently in charge so that the whole team can make beautiful music together? Bramwell Tovey of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra stepped off his podium to talk about the job. “The hard part,” he said, “is the rehearsal process,” not the performance. That’s less grand. And how about being in such control? “You have to subordinate yourself to the composer,” he said. So, does the orchestra “director” actually direct the orchestra—exercise that famous leadership? “We never talk about ‘the relationship,’” was the response. So much for that metaphor.

Twenty-nine Days of Managing

I could go on. This is the tip of the managerial iceberg. I spent a day with each of these and other managers—twenty-nine in all—observing, interviewing, reviewing their diaries over a week or a month, to interpret what was going on. The evidence from that research informs this book.

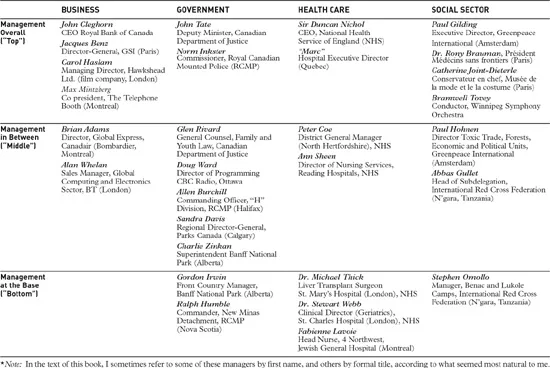

As shown in Table 1.1, these managers came from business, government, health care, and the social sector (nongovernmental organizations [NGOs], not-for-profits, etc.),4 and from all sorts of organizations, including banking, policing, filmmaking, aircraft production, retailing, telecommunications. Some of these organizations were tiny, others huge (from 18 to 800,000 employees). These managers spanned all the conventional levels of the hierarchy, from the so-called top and middle to the base. Some worked in major urban centers (London, Paris, Amsterdam, Montreal); others, in more out-of-the-way places (N’gara, Tanzania; New Minas, Nova Scotia; the Banff National Park in western Canada). Some were observed singly; others, in clusters (e.g., three managers of the Canadian parks, who reported to each other, on three successive days).

For each day (or cluster of days), I described what I saw and then interpreted it in conceptual terms. I let each speak for itself. And speak they did—for example, about how old-fashioned managing by exception can be very up-to-date; about how the managers of Greenpeace have to give as much attention to the sustainability of their organization as to the sustainability of our environment; about how the real politics of government may happen on the ground, where the bears meet the tourists. These days also spoke to the wide variety of contexts in which management happens: I found myself holding on the back of a motorcycle for dear life at it raced through Paris, from one press interview to another; sitting alone in a concert hall of 2,222 velvet seats watching a conductor rehearsing an orchestra; lunching once in a restaurant established by an enterprising refugee in an African camp, and another time freezing in the Greenpeace cafeteria in Amsterdam; walking in a pristine park discussing “bear jams” (traffic jams caused by motorists who stop to see the bears that have ambled down to the highway). All of this, I assure you, provides a wonderful setting to contemplate management and life—since managing is about so much of life.

Table 1.1 THE TWENTY-NINE MANAGERS OBSERVED*

A single day, albeit reinforced by discussion of other days, is hardly a long time. But it is remarkable what can come from straight and simple observation, with no agenda other than letting reality hit you in the face. As Yogi Berra, the sage of American baseball, put it: “You can observe a lot just by watching.” Combine all twenty-nine days, and you have a good deal of evidence about the practice of managing.

Throughout the book, I weave in illustrations from these twenty-nine days, both the descriptions of what happened and the conceptual interpretations of why it happened. Eight of these descriptions are reproduced in the appendix, to anchor the book. The descriptions and interpretations of all twenty-nine days have been made available on a Web site (www.mintzberg-managing.com). To give a sense of this, let me quote some of the titles of the write-ups that appear on the site and figure in the later chapters:

• “Managing on the Edges”—about the political pressures experienced by those managers in the Canadian parks

• “Managing Up, Down, In, and Out”—about the effects of hierarchical level on five managers of the huge National Health Service (NHS) of England, from the chief executive to two head clinicians in hospitals

• “Hard Dealing and Soft Leading”—about the contrast in the work of the head of a film company, between managing externally and internally

• “The Yin and Yang of Managing”—contrasting the work of two chief executives, one of a fashion museum, the other of Doctors Without Borders, both in Paris but worlds apart

• “Managing Exceptionally”—about two Red Cross managers in that refugee camp in Tanzania, managing by exception in exceptional ways

Before proceeding, it will be helpful in this opening chapter to revisit three other myths that get in the way of seeing managing for what it is: that it is somehow separate from leadership; that it is a science, or at least a profession; and that managers, like everyone else, live in times of great change.

Leadership Embedded in Management and Communityship

It has become fashionable to distinguish leaders from managers (Zaleznik 1977, 2004; Kotter 1990a, 1990b). One does the right things, copes with change; the other does things right, copes with complexity. So tell me, who are the leaders and who are the managers in the examples described earlier? Was Alan Whelan merely managing at BT, and Bramwell Tovey merely leading on, and off, the podium? How about Jacques Benz in that project meeting at GSI? Was he doing the right things or doing things right?

Frankly, I don’t understand what this distinction means in the everyday life of organizations. Sure, we can separate leading and managing conceptually. But can we separate them in practice? Or, more to the point, should we even try?

How would you like to be managed by someone who doesn’t lead? That can be awfully dispiriting. Well, then, why would you want to be led by someone who doesn’t manage? That can be terribly disengaging: how are such “leaders” to know what is going on?5 As Jim March put it: “Leadership involves plumbing as well as poetry” (2004:173).

I observed John Cleghorn, Chairman of the Royal Bank of Canada, who developed a reputation in his company for calling the office on his way to the airport to report a broken ATM machine and such things. This bank has thousands of such machines. Was John micromanaging? Maybe he was setting an example that others should keep their eyes open for such problems.

In fact, today we should be more worried about “macroleading”—people in senior positions who try to manage by remote control, disconnected from everything except “the big picture.” It has become popular to talk about us being overmanaged and underled. I believe we are now overled and undermanaged.

Konosuke Matsushita, who founded the company that carries his name, claimed, “Big things and little things are my job. Middle level arrangements can be delegated.” In other words, leadership cannot simply delegate management; instead of distinguishing managers from leaders, we should be seeing managers as leaders, and leadership as management practiced well.

Whether in the confines of academia or the columns of newspapers, it is a lot easier to muse about the glories of leadership than it is to come to grips with the realities of management. Obviously this comes at the expense of management, but it has also undermined leadership itself. The more we obsess about leadership, the less of it we seem to get. In fact, the more we claim to develop leadership in courses and programs (I counted the words leader and leadership over fifty times on the Harvard MBA Web site in 2007), the more we get hubris. That is because leadership is earned, not anointed.

Moreover, by putting leadership on a pedestal separated from management, we turn a social process into a personal one. No matter how much lip service is paid to the leader empowering the group, leadership still focuses on the individual: whenever we promote leadership, we demote others, as followers. Slighted, too, is the sense of community that is important for cooperative effort in all organizations. What we should be promoting instead of leadership...