CHAPTER 1. Europe Classical and Medieval

European civilisation is unique because it is the only civilisation which has imposed itself on the rest of the world. It did this by conquest and settlement; by its economic power; by the power of its ideas; and because it had things that everyone else wanted. Today every country on earth uses the discoveries of science and the technologies that flow from it, and science was a European invention.

At its beginning European civilisation was made up of three elements:

1. the culture of Ancient Greece and Rome

2. Christianity, which is an odd offshoot of the religion of the Jews, Judaism

3. the culture of the German warriors who invaded the Roman Empire.

European civilisation was a mixture: the importance of this will become clear as we go on.

*

If we look for the origins of our philosophy, our art, our literature, our maths, our science, our medicine and our thinking about politics — in all these intellectual endeavours we are taken back to Ancient Greece.

In its great days Greece was not one state; it was made up of a series of little states: city-states, as they are now called. There was a single town with a tract of land around it; everyone could walk into the town in a day. The Greeks wanted to belong to a state as we belong to a club: it was a fellowship. It was in these small city-states that the first democracies emerged. They were not representative democracies; you did not elect a member of parliament. All male citizens gathered in one place to talk about public affairs, to vote on the laws and to vote on policy.

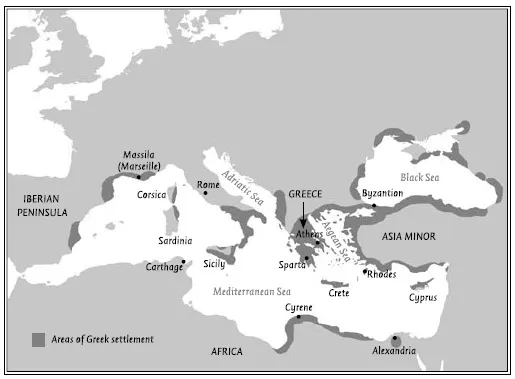

Ancient Greek cities and colonies. Greek civilisation thrived in trading and agricultural colonies around the Mediterranean and Black Seas.

As these Greek city-states grew in population, they sent people to start colonies in other parts of the Mediterranean. There were Greek settlements in what is now Turkey, along the coast of North Africa, even as far west as Spain, southern France and southern Italy. And it was there — in Italy — that the Romans, who were then a very backward people, a small city-state around Rome, first met the Greeks and began to learn from them.

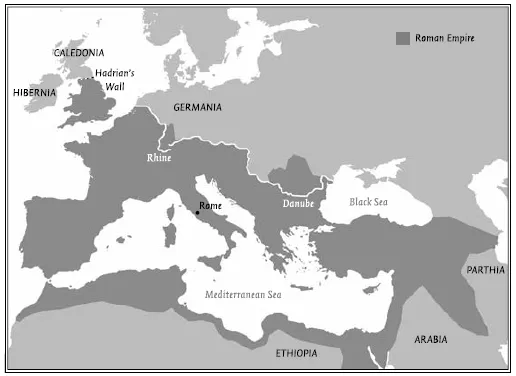

In time the Romans built a huge empire that encompassed Greece and all the Greek colonies. In the north the boundaries were two great rivers, the Rhine and the Danube, though sometimes these were exceeded. In the west was the Atlantic Ocean. England was part of the Roman Empire but not Scotland or Ireland. To the south were the deserts of North Africa. In the east the boundary was most uncertain because here were rival empires. The empire encircled the Mediterranean Sea; it included only part of what is now Europe and much that is not Europe: Turkey, the Middle East, North Africa.

The extent of the Roman Empire around the second century AD.

The Romans were better than the Greeks at fighting. They were better than the Greeks at law, which they used to run their empire. They were better than the Greeks at engineering, which was useful both for fighting and running an empire. But in everything else they acknowledged that the Greeks were superior and slavishly copied them. A member of the Roman elite could speak both Greek and Latin, the language of the Romans; he sent his son to Athens to university or he hired a Greek slave to teach his children at home. So when we talk about the Roman Empire being Greco-Roman it is because the Romans wanted it that way.

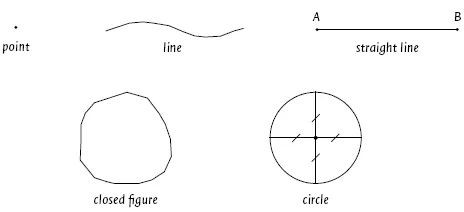

Geometry is the quickest way to demonstrate how clever the Greeks were. The geometry taught in school is Greek. Many will have forgotten it, so let’s start with the basics. That is how geometry works; it starts with a few basic definitions and builds on them. The starting point is a point, which the Greeks defined as having location but no magnitude. Of course it does possess magnitude, there is the width of the dot on the page, but geometry is a sort of make-believe world, a pure world. Second: a line has length but no breadth. Next, a straight line is defined as the shortest line joining two points. From these three definitions you can create a definition of a circle: in the first place, it is a line making a closed figure. But how do you formulate roundness? If you think about it, roundness is very hard to define. You define it by saying there is a point within this figure, one point, from which straight lines drawn to the figure will always be of equal length.

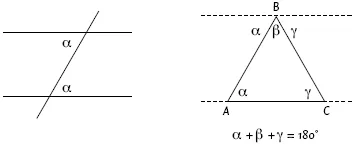

Along with circles, there are parallel lines that extend forever without meeting, and triangles in all their variety, and squares and rectangles and other regular forms. These objects, formed by lines, are all defined, their characteristics revealed and the possibilities arising from their intersection and overlapping explored. Everything is proved from what has been established before. For example, by using a quality of parallel lines, you can show that the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees (see below).

GEOMETRY IN ACTION

Parallel lines do not meet. We can define this characteristic by saying that a line drawn across them will create alternate angles that are equal. If they were not equal, the lines would come together or they would diverge — they would not be parallel. We use letters from the Greek alphabet to identify an angle — and on the diagram on the left α marks two angles that are equal. The use of letters from the Greek alphabet for the signage in geometry reminds us of its origins. Here we use the first three letters: alpha, beta and gamma.

From this definition we can determine the sum of the angles within a triangle. We put the triangle ABC on the right within two parallel lines: knowing how to bring into play what is known to solve what is unknown is the trick of geometry. The angle α at point A has an angle that is equal to it at point B, on the basis that they are alternate angles across parallel lines. Likewise the angle γ at C has an angle equal to it at point B. The top parallel line at B is now made up of three angles: α + β + γ. Together they make a straight line, and we know that straight lines make an angle of 180 degrees.

So α + β + γ = 180 degrees. And we have established, using parallel lines, that the sum of the internal angles of the triangle is also α + β + γ. So the sum of the internal angles of a triangle is 180 degrees.

We have used parallel lines to prove something about triangles.

Geometry is a simple, elegant, logical system, very satisfying, and beautiful. Beautiful? The Greeks found it beautiful and that they did so is a clue to the Greek mind. The Greeks did geometry not just as an exercise, which is why we did it at school, nor for its practical uses in surveying or navigation. They saw geometry as a guide to the fundamental nature of the universe. When we look around us, we are struck with the variety of what we see: different shapes, different colours. A whole range of things is happening simultaneously — randomly, chaotically. The Greeks believed there was some simple explanation for all this. That underneath all this variety there must be something simple, regular, logical which explains it all. Something like geometry.

The Greeks did not do science as we do, with hypotheses and testing by experiment. They thought if you got your mind into gear and thought hard you would get the right answer. So they proceeded by a system of inspired guesses. One Greek philosopher said all matter is made up of water, which shows how desperate they were to get a simple answer. Another philosopher said all matter is made up of four things: earth, fire, air and water. Another philosopher said all matter is actually made up of little things which he called atoms — and hit the jackpot. He made an inspired guess which we came back to in the twentieth century.

When science as we know it began 400 years ago, 2000 years after the Greeks, it began by upsetting the central teachings of Greek science, which remained the authority. But it upset the Greeks by following this Greek hunch that the answers would be simple and logical and mathematical. Newton, the great seventeenth-century scientist, and Einstein, the great twentieth-century scientist, both said you will only get close to a correct answer if your answer is simple. They were both able to give their answers in mathematical equations which described the composition of matter and how matter moves.

The Greeks were often wrong in their guesses, very wrong. Their fundamental hunch that the answers would be simple, mathematical and logical could have been wrong too, but it turned out to be right. This is the greatest legacy that European civilisation still owes to the Greeks.

Can we explain why the Greeks were so clever? I don’t think we can. Historians are meant to be able to explain things but when they come up against the big things — why, for example, in these little city-states there were minds so logical, so agile, so penetrating — they have no convincing explanation. All historians can do, like anyone else, is wonder.

Here is another miracle. We are coming to the second element in the European mix. The Jews came to believe that there was only one god. This was a very unusual view. The Greeks and Romans had the more common belief that there were many gods. The Jews had an even more extraordinary belief that this one god took special care of them; that they were God’s chosen people. In return, the Jews had to keep God’s law. The foundation of the law was the Ten Commandments, given to the Jews by Moses who had led them out of captivity in Egypt. Christians retained the Ten Commandments and they remained the central moral teaching in the West until recent times. People knew the commandments by number. You might say of someone that he would never break the eighth commandment but sometimes he broke the seventh. Here are the Ten Commandments, as recorded in the second book of the...