Why a Painting Is Like a Pizza

A Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Modern Art

Nancy G. Heller

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

Why a Painting Is Like a Pizza

A Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Modern Art

Nancy G. Heller

Información del libro

The first time she made a pizza from scratch, art historian Nancy Heller made the observation that led her to write this entertaining guide to contemporary art. Comparing modern art not only to pizzas but also to traditional and children's art, Heller shows us how we can refine analytical tools we already possess to understand and enjoy even the most unfamiliar paintings and sculptures.

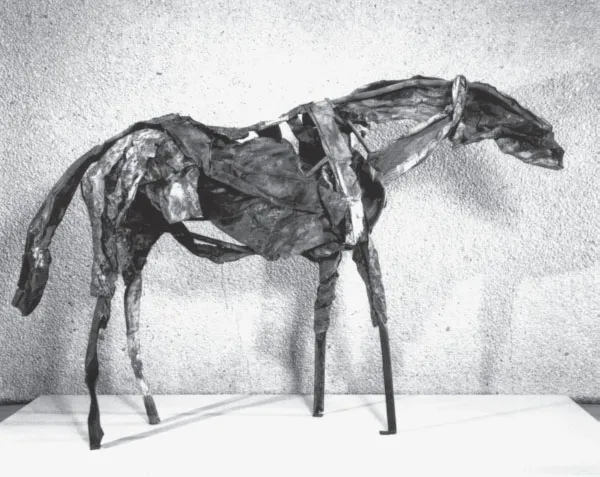

How is a painting like a pizza? Both depend on visual balance for much of their overall appeal and, though both can be judged by a set of established standards, pizzas and paintings must ultimately be evaluated in terms of individual taste. By using such commonsense examples and making unexpected connections, this book helps even the most skeptical viewers feel comfortable around contemporary art and see aspects of it they would otherwise miss. Heller discusses how nontraditional works of art are made--and thus how to talk about their composition and formal elements. She also considers why such art is made and what it "means."

At the same time, Heller reassures those of us who have felt uncomfortable around avant-garde art that we don't have to like all--or even any--of it. Yet, if we can relax, we can use the aesthetic awareness developed in everyday life to analyze almost any painting, sculpture, or installation. Heller also gives concise answers to the eight questions she is most frequently asked about contemporary art--from how to tell when an abstract painting is right side up to which works of art belong in a museum.

This book is for anyone who agrees with art critic Clement Greenberg that "All profoundly original art looks ugly at first." It's also for anyone who disagrees. It is for anyone who wants to get more out of a museum or gallery visit and would like to be able to say something more than just "yes" or "no" when asked if they like an artist's work.

Preguntas frecuentes

Información

1

EXACTLY WHAT IS “ABSTRACT” ART?

“Art. This word has no definition.”Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary, 1906

2

WHY IS A PAINTING LIKE A PIZZA?

“To see is itself a creative operation, requiring an effort.”Henri Matisse