eBook - ePub

Vegetarian Myth

FOOD, JUSTICE AND SUSTAINABILITY

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 312 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Vegetarian Myth

FOOD, JUSTICE AND SUSTAINABILITY

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

The vegetarian diet is praised for being sustainable and animal-friendly, but after 20 years of being a vegan, Lierre Keith has changed her opinion. Contravening popular opinion, she bravely argues that agriculture is a relentless assault against the planet. In service to annual grains, humans have devastated prairies and forests, driven countless species extinct, altered the climate, and destroyed the topsoil - the basis of growth and life itself.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Vegetarian Myth un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Vegetarian Myth de en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politics & International Relations y Political Advocacy. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Politics & International RelationsCategoría

Political AdvocacyCHAPTER 4

Nutritional Vegetarians

Start with Africa seven million years ago, because that’s where human life began. The climate, the creation of our ancestors—our beloved kin of bacteria, fungi, and plants—eased from wet to dry. The trees gave way to grasses and a tide of savannas rippled across the world. Cradled in the grasses were large herbivores. Twenty-five million years ago, in the exuberance of evolution, a few plants tried growing from their bases instead of their tips. Grazing would not kill these plants; quite the opposite. It would encourage them by stimulating root growth. All plants want nitrogen and predigested nutrients, and ruminants could provide those to the grasses as they grazed. This is why, unlike other plants, grasses contain no toxins or chemical repellents, no mechanical deterrents like thorns or spines to discourage animals. Grasses want to be grazed. It was grass that created cows; human “domestication” was, in comparison, just the tiniest tug on the bovine genome, and cows tugged back with the lactose tolerance gene.

Our direct line lived in trees, until the trees began to disappear. We had two evolutionary edges to see us through: our opposable thumbs and our omnivorous digestion. We had the capacity to manipulate tools and we had bodies equipped with both the instincts and the digestion to handle a range of foods. Some animals are monofeeders: koalas eat only eucalyptus, and fig wasps dine only on figs. Monofeeding is a gamble; if your food source fails, you go down with it. But a brain, which is a huge energy sink, can be small for a monofeeder, which spares energy for every other function.

Chocolate notwithstanding, humans are not monofeeders. Back before we were human, when we were tree dwellers, we ate mainly fruit, leaves, and insects. But from the moment we stood upright, we’ve been eating large ruminants. Four million years ago, Australopithecines, our species’ forerunners, ate meat.

Australopithecines were once believed to be fruitivores: the dividing line between the Homo genus and Australopithecines was thought to be the taste for meat. But the teeth of four three-million-year-old skeletons in a South African cave told a different story. Anthropologists Matt Sponheimer and Julia Lee-Thorp found Carbon-13 in the tooth enamel of those skeletons. Carbon-13 is a stable isotope present in two places: grasses and the bodies of animals that eat grass. Those teeth showed none of the scratch marks of grass consumption.1

Australopithecine was eating grass-feeding animals, the large ruminants swaddled in savanna.

Stone tools have laid beside the bones of long-extinct animals, buried in a silence of time, for 2.6 million years. Together, tools and bones have waited to tell their story, the story of us. Some of the bones show teeth marks overlaid by tool cut marks: a carnivore kill followed by a human scavenger. Other bones bear the opposite: cut marks, then the marks of sharp teeth, saying there was a human with a weapon, then an animal with teeth. We come from a long line of hunters: 150,000 generations.2

This is what our line learned, and in the learning, we became human. We made tools to take what the grasses offered: large animals laden with nutrients, more nutrients than we could ever hope to find in fruit and leaves. The result is reading these words. Our brains are twice as large as they should be for a primate our size. Meanwhile our digestive tracts are 60 percent smaller. Our bodies were built by nutrient-dense foods. Anthropologists L. Aiello and P. Wheeler named this idea “The Expensive Tissue Hypothesis.” The Australopithecine brain grew to Homo proportions because meat let our digestive systems shrink, thus freeing up energy for those brains.3

Or compare humans to gorillas. Gorillas are vegetarians and they have both the smallest brains and the largest digestive tracts of any primate. We are the opposite. And our brains, the true legacy of our ancestors, need to be fed.

The vegetarians have their own story, a very different one than the one told in the bones and tools, teeth and skulls. “Real strength and building material comes from green-leafed vegetables where the amino acids are found,” writes one vegan guru. “If we look at the gorilla, zebra, giraffe, hippo, rhino, or elephant we find they build their enormous musculature on green-leafy vegetation.”4 Actually, if we really look at gorillas et al., what we find are animals that contain the fermentative bacteria necessary to digest cellulose. We humans contain no such thing. This man writes books about diet without knowing a thing about how humans actually digest.

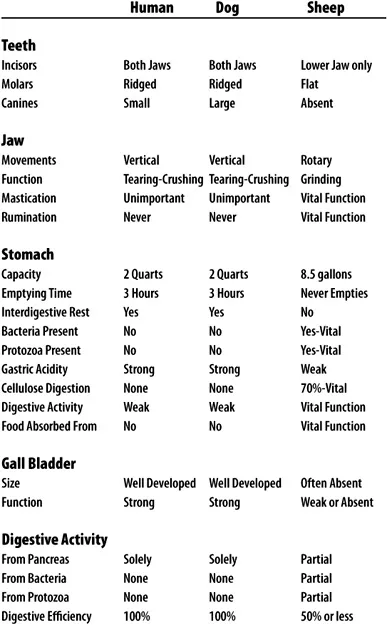

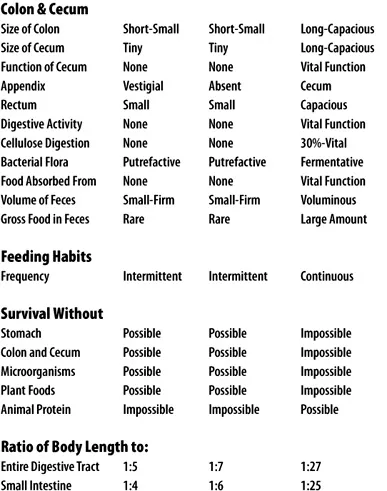

For most of us, the bodies beneath our skin, inside our ribs, are unknown territory. But if we lay aside the story we long for and listen to our bodies, our biology will not lie. Here, then, is the long history that trees and savanna, grass and herds, have told in human tissue. (See table on following pages.)

There are two small differences between humans and dogs. One is that our canine teeth are shorter. The consensus is that ours were once longer than they currently are, but that they shrank due to our use of fire and tools. The other difference is that our intestines are longer, though clearly nowhere near as long as a sheep’s. This is the remnant of our distant history as tree-dwelling fruitivores. And it’s what grants us omnivorous status. But the chart on the following page should make clear what political and emotional attachments—and the FDA food pyramid—have obscured: we are built to consume meat, for the protein and fat it provides. Write Drs. Michael and Mary Dan Eades, “In anthropological scientific circles, there’s absolutely no debate about it—every respected authority will confirm that we were hunters.… Our meat-eating heritage … is an inescapable fact.”5

There is another version of the story as well, one written by humans, not bones and teeth. This version lay waiting 40,000 years in caves from South Africa across Eurasia, and it’s told in pictures. Some are schematics, the bare outlines of what matters. Others are lush with texture and detail, the elements arranged so that the curves of the walls supply dimension and motion. “These bison,” writes one observer, “seem to leap from a corner of the cave.”6 Or, as Pablo Picasso said on viewing the cave art of Lascaux, “We have invented nothing in twelve thousand years.” No, we haven’t. And even 40,000 years ago, it wasn’t just us. The wild herds of aurochs and horses invented us out of their bodies, their nutrient-dense tissues gestating the human brain.

Some writers want to argue that hunting was the first act of domination, of political oppression. Yet life is only possible through death. Everything is dependent on killing, either directly or indirectly: you’re either doing it or waiting for someone else to do it for you. Animals from praying mantids to bears hunt, and have you seen a kudzu vine take down a tree? Yet none of them, animal or vegetable, set up CAFOs or concentration camps. And though the human species must also kill, plenty of cultures have been built around reciprocity, humility, and basic kindness. If the getting of food, of life, means we are destined for sadism and genocide, then the universe is a sick and twisted place and I want out. But I don’t believe it. It hasn’t been my experience of food, of killing, of participating. When I see the art that people who were our anatomical equals made, I don’t see a celebration of cruelty, an aesthetic of sadism. No, I wasn’t there when the drawings were made and I didn’t interview the artists. But I know beauty when I see it.

And the artists left no question about what they were eating. Besides their drawings, they also left weapons, including blades for killing and butchering. The tools are exquisite in their precision—and the ones made of wood are the oldest wooden objects ever found.

Archaeologists have dated an almost sixteen-inch-long spear tip carved of yew wood, found in 1911 in Clacton, England, to be somewhere between 360,000 and 420,000 years old. Another spear, also made of yew, is almost eight feet long and is 120,000 years old. It was found amid the ribs of an extinct elephant in Lehringen, Germany, in 1948. Excavators in a coal mine near Schoninger, Germany, found three spruce wood spears shaped like modern javelins—the longest of which measured over seven feet—that proved to be 300,000 to 400,000 years old.7

And our ancestors knew how to use their tools. Fairweather Eden is the story of the archaeological excavation in Boxgrove, England, a site lush with extinct rhinoceroses and wild horses, mammoths and cave bears. These animals were dangerous, large and strong, and not without defenses: a cave bear had teeth that were three inches long and “the jaw strength to snap a man in two.”8 If we could have simply lived on foraged fruit, wouldn’t we have? But our hunger gave us courage, enough that we grew skilled. The archaeologists at Boxgrove took flint tools and a fresh-killed deer to the local butcher and asked him to take it apart with the tools. Five hundred thousand years later, the modern cut marks were exactly the same as the ancient ones.9 We have, indeed, invented nothing.

Except agriculture. And with agriculture comes the “diseases of civilization.” Understand that no one speaks of the “diseases of hunter-gatherers,” because they are largely disease-free. Not so the farmers, who have destroyed their bodies along with the planet. The list of diseases includes “[a]rthritis, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, depression, schizophrenia, and cancer,” as well as crooked teeth, bad eyesight, and a whole host of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions.10

These diseases are ubiquitous amongst the civilized and “are absolute rarities” for hunter-gatherers. 11 Writes Dr. Loren Cordain, in his article “Cereal Grains: Humanity’s Double-Edged Sword”:

Cereal grains as a staple food are a relatively recent addition to the human diet and represent a dramatic departure from those foods to which we are genetically adapted. Discordance between humanity’s genetically determined dietary needs and his [sic] present day diet is responsible for many of the degenerative diseases which plague industrial man.… [T]here is a significant body of evidence which suggests that cereal grains are less than optimal foods for humans and that the human genetic makeup and physiology may not be fully adapted to high levels of cereal grain consumption.12

The archaeological evidence is incontrovertible, as is the living testament of the last extant eighty-four tribes of hunter-gatherers. They are eating the diet that all humans evolved to eat: “meat, fowl, fish and leaves, roots and fruits of many plants.”13 We are eating foods that didn’t even exist until a few thousand years ago: domesticated annuals, especially grains, and even more their industrial endpoint of refined flours, sugars, and oils. As Cordain points out, “More than 70% of our dietary calories come from foods that our Paleolithic ancestors rarely, if ever, ate.”14 Our own bodies, with their degenerative diseases and overgrowth of cells, are all the evidence we need that this diet is unnatural.

So this is how we know what our ancestors ate: our teeth are made for meat, not cellulose; our stomachs are singular and secrete acid; both the tooth enamel and the art of our ancestors say so; human butchering tools are found beside butchered bones; and, to state the obvious, contemporary hunter-gatherers hunt.

One version of the vegetarian myth posits that we were “gatherer-hunters,” gaining more sustenance from plants gathered by women than from meat hunted by men. This rumor actually has an author, one R.B. Lee, who concluded that hunter-gatherers got 65 percent of their calories from plants and only 35 percent from animals. This 65:35 figure has been repeated endlessly across disciplines, and it simply isn’t true. Dr. Cordain ran a computer model with the plant foods accessible to hunter-gatherers. To meet their caloric needs alone, the 65:35 ratio would require eating twelve pounds of vegetation every day. “[A]n unlikely scenario, to say the least,” comment the Drs. Eades.15 Lee got his data from Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas, a collection of statistics from 862 different cultures. Of the 181 hunter-gatherer societies, Lee included only fifty-eight. He didn’t count fish in his numbers, and he put shellfish in the “gathering” column. Tell me, have you ever been in danger of mistaking a lobster for a wild berry? The Ethnographic Atlas also classifies small land fauna—insects, grubs, reptiles, small mammals—as plants, by describing their collection as gathering. Cordain refigured the numbers as best he could, by reclassifying fish and shellfish as hunting, and by using data for all the available hunter-gatherers. His conclusion completely reversed Lee’s numbers. He suggests that the true ratio is closer to 65 percent animal to 35 percent plants. And that’s still including the Ethnographic Atlas’s bias of small land fauna as plants.16

The first myth of the nutritional vegetarians—that we aren’t meant for meat—is another fairy tale filled with inedible apples. I try to remember what I believed when I was a vegan. There was a mythic golden age, long ago, when we lived in harmony with the world … and … ate what? Prehistoric paintings of humans hunting left me confused and defensive, but I was unclear on the timeline anyway. Maybe all tha...