eBook - ePub

Red Road from Stalingrad

Recollections of a Soviet Infantryman

Mansur Abdulin, Artem Drabkin

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 195 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Red Road from Stalingrad

Recollections of a Soviet Infantryman

Mansur Abdulin, Artem Drabkin

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Mansur Abdulin fought in the front ranks of the Soviet infantry against the German invaders at Stalingrad, Kursk and on the banks of the Dnieper. This is his extraordinary story. His vivid inside view of a ruthless war on the Eastern Front gives a rare insight into the reality of the fighting and into the tactics and mentality of the Soviet army. In his own words, and with a remarkable clarity of recall, he describes what combat was like on the ground, face to face with a skilled, deadly and increasingly desperate enemy.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Red Road from Stalingrad un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Red Road from Stalingrad de Mansur Abdulin, Artem Drabkin en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Historia y Segunda Guerra Mundial. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

HistoriaCategoría

Segunda Guerra MundialContents

| Editorial Preface | |

| Maps | |

| One | The Front |

| Two | First Attack |

| Three | The Man Killed by a Sewing Machine |

| Four | Born Under a Lucky Star |

| Five | Holiday Presents for the Fritzes |

| Six | Pitomnik Airfield |

| Seven | A Captured Gold Watch |

| Eight | Kostia’s Tiger |

| Nine | The Drunkards’ Cemetery |

| Ten | The Fatal Road |

| Eleven | How Long Will This War Last? |

| Twelve | My Last Shot |

| Epilogue | |

| Appendix I: | The 293rd Rifle Division |

| Appendix II: | Stalingrad, Kursk, and the Dnieper |

| Appendix III: | Chronology of Major Events |

| Index |

Editorial Preface

‘This must never happen again!’ Such was the slogan proclaimed after the Great Victory, which became an important principle in Soviet domestic and foreign policy. Winning, together with its allies, the bloodiest war in history, the country suffered enormous losses. Almost 27 million people perished (almost 15 per cent of the peacetime population). Millions of my compatriots were killed in action, ended their lives in German concentration camps, starved or froze to death in besieged Leningrad or in evacuation. The ‘scorched earth’ policy, which both armies pursued during retreat, resulted in the total destruction of the lands which before the war counted a population of 88 million and had produced up to 40 per cent of GDP. Millions of people lost their homes and were forced to live in abominable conditions. The fear that such a catastrophe might repeat itself haunted the nation. It was one of the reasons that the country’s leadership adopted an enormous defense budget, which became a terrible strain for the economy. Because of this very real fear, ordinary people used to store a certain amount of ‘strategic products’ – salt, matches, sugar, canned goods … I remember as kid how my grand mother – who had lived through the famine of war – kept trying all the time to give me something to eat, and was very distressed when I refused! We children, born some thirty years after the war, continued to refight it in our play, in the streets. We divided into groups of ‘our men’ and ‘Germans’ and the first German words we learned were ‘Hände hoch,’ ‘Nicht schiessen,’ and ‘Hitler Kaputt.’ In almost every house one could see some reminder of the war. I still have my father’s decorations and a German case for gas mask filters standing in the corridor of my flat – it’s a good thing to sit on when you’re tying your shoelaces!

A desire to forget the horrors of the war as fast as possible, to heal its wounds–as well as to conceal the mistakes of the country’s leadership and military chiefs–led to a propaganda campaign based on the image of a faceless Soviet soldier, ‘bearing on his shoulders the full weight of the struggle with German fascism,’ while praising the ‘heroism of the Soviet people.’ This attitude meant propagating a simplified, strictly official interpretation of what really happened. As a result, those memoirs published in the Soviet era were strongly affected by both external and internal censorship. Only in the late eighties could the full truth about the war come to light.

That was the decade Mansur Abdulin’s book was published. Last year, when I saw it for the first time, I realized that here I held a true confession of the ‘heroic Soviet people’, written by a highly original man. What makes these memoirs absolutely unique is that Abdulin was involved in front line action for a whole year, while statistics tell us that on average, a Red Army infantryman survived the battlefield for only a fortnight, after which he was either killed or wounded. This period of time allowed Mansur to gain a wealth of experience, which he relates in this book. Being a gifted story-teller, Abdulin, in a frank and straightforward way, describes his life in the trenches. He was perfectly aware that the carnage, which he was forced to be a part of, left him practically no chance of survival. His main goal was to sell his life as dearly as possible, which meant killing others, killing as many enemy soldiers as he was able. The war on the Eastern Front was marked by an amazing degree of hatred and violence, connected largely with the German intentions of totally annihilating the USSR and enslaving its population. The Western reader has already had an opportunity to learn of the experiences of the German side, by reading the books of such veterans as Guy Sajer or Günter K. Koschorrek, while memoirs of Soviet soldiers were almost totally inaccessible. This is why I instantly felt enthusiastic about an English edition.

But how could I find the author? The book was published thirteen years ago and Abdulin must be no less than eighty by now. Was he alive? How could I reach him? It was mentioned in the accompanying text that Mansur Abdulin resides in Novotroitsk, in the Orenburg Region. I called the information office of this small town situated in the Southern Urals. The girl at the other end of the line misspelled the surname at first, and answered that she didn’t have such a man on her list. My heart sank! ‘What did you say the name was?’ ‘Abdulin.’

‘Sorry, I was looking for “Abdullin”. Just a moment … Yes, we have an Abdulin M.G.’ I immediately phoned Mansur and introduced myself: ‘How would you feel about preparing an English edition of your book?’ ‘Why not? Let’s give it a try …’

Artem Drabkin,

Moscow 2004

Moscow 2004

Maps

The Eastern Front showing Mansur Abdulin’s route

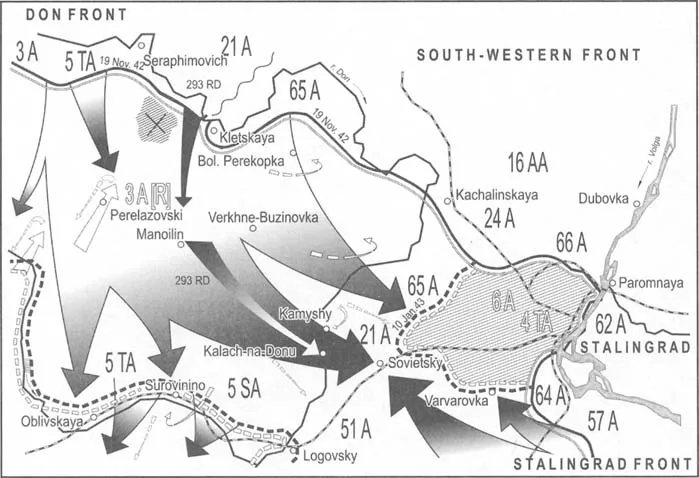

‘Operation Uranium’: encirclement of the Sixth Army in Stalingrad

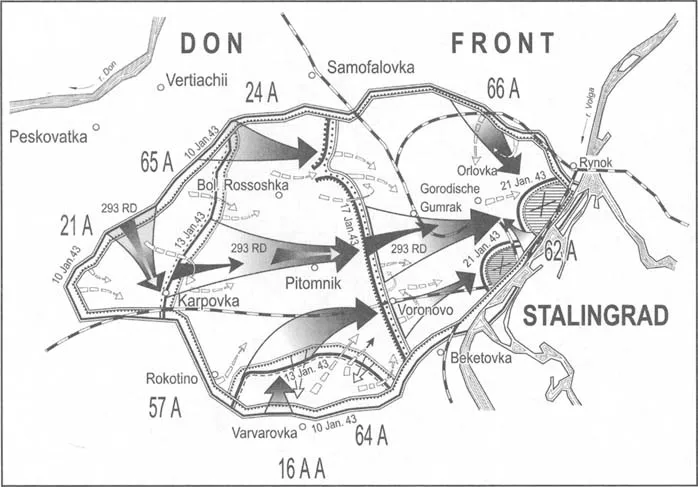

‘Operation Kol ‘tso’ (Ring): liquidation of Stalingrad pocket

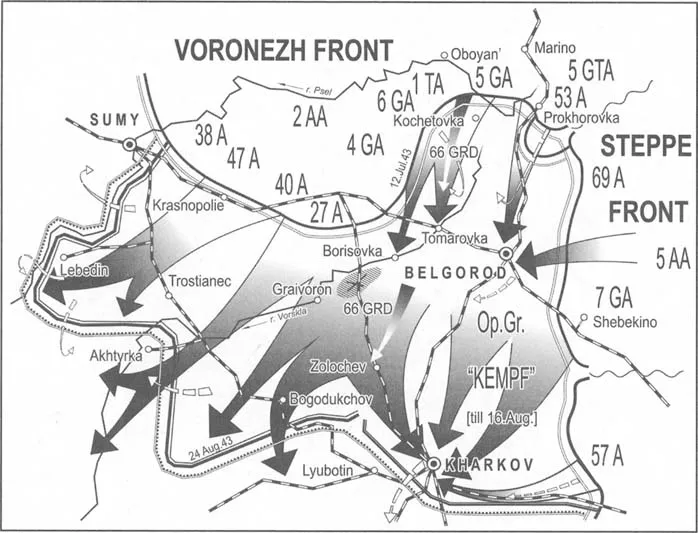

Belgorod-Kharkov: the ‘Rumiantsev’ strategic offensive

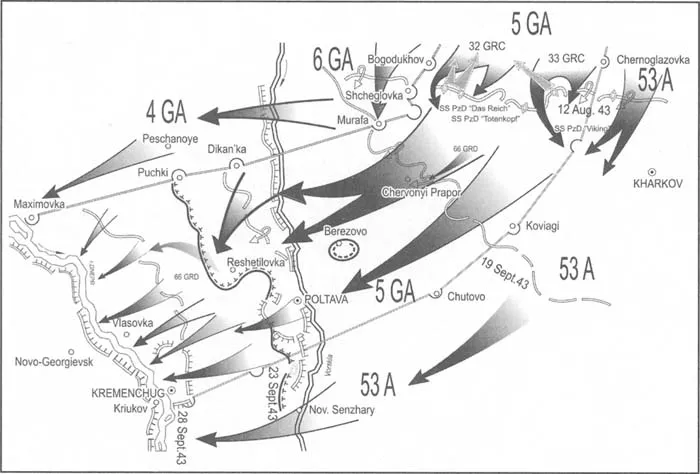

Advance to the Dnieper: operations of 5th Guards Army in the Ukraine campaign

The Eastern Front showing Mansur Abdulin’s route

‘Operation Uranium’: encirclement of the Sixth Army in Stalingrad

‘Operation Kol ‘tso’ (Ring): liquidation of Stalingrad pocket

Belgorod-Kharkov: the ‘Rumiantsev’ strategic offensive

Advance to the Dnieper: operations of 5th Guards Army in the Ukraine campaign

CHAPTER ONE

The Front

The war, the front, means shooting. Mortars, machine- and submachine guns, artillery. I made my first shot in action on 6 November 1942, on the South-Western Front, from an autoloading SVT rifle. This is how it was …

A couple of days before the attack, every company held solemn meetings, ‘dedicated to the 25th Anniversary of our Soviet State.’ We took an oath to carry out the order of the Motherland – ‘No retreat!’ – then we crossed the Don. The river was quiet, the passage went well, and at a rapid pace, we entered a ravine high on the right bank.

‘Watch your step!’ We keep hearing this warning, and for us mortarmen, it has an important and specific meaning. Mortarmen are loaded with gun carriages, barrels and base-plates: if you are moving fast, and fall or flounder, the equipment – because of the momentum – can crush the back of your skull. I have seen many lightly wounded soldiers stumble, only to be finished off by their heavy load.

We are advancing over a kind of waste ground. We seem to be stepping on old sacks and clumps of grass: in the dark we can’t see what’s beneath our feet. What bothers us is some stinking smell. We run away from it, forward, forward! A violet flare appears in the sky, and in its light we see the faces of the dead. Both Germans and our own men.

More flares. I furtively look at my comrades: do they see them? Yes, they do. But everyone seems calm. No one makes a fuss. Not even a swear word. War is war. This is how it is. And what can be more natural! I have just turned nineteen and I know that the others are about the same age. Everyone has had a similar experience: a quick course of practice shoots at the Tashkent Infantry School.

I jump over dead bodies, and in my mind flashes a thought: how quickly men become accustomed to things which, at one time, they would have found impossible to imagine. Another thought – and a strange one in such circumstances – I am satisfied with myself. If a comrade glanced at me, he would see nothing but a common expression of concentration. At the front, being like everyone else – that is, no worse than the others – means being assured of one’s value. A very important thing for self-respect. However startled I was by the sickening scene illuminated by the flare (the true face of war, its essence, when notices like ‘Died a valiant death’ are issued), I, nevertheless, am doing all the necessary things, just like the other men: trying not to stumble, ducking down when the whistling bullets fly.

We run the final few metres bent double. The ravine is becoming shallower: now the bullets whizz very low. Eventually I jump into the trench: alive, no bruises, my knapsack and gun right here. A few minutes to catch my breath and I’m ready to fire whenever the order comes.

‘What took you so long?’ We hear harsh voices, some foul language, then the front line soldiers vanish from the trenches, like ghosts into thin air. Loaded with their mortars and machine-guns, they march past us into the ravine from which we have just emerged. I had anticipated a different reception, and the instant disappearance of the trenches’ preceding inhabitants leaves an unpleasant impression. Probably I expected the ‘old men’ to stay with us a while, to show us what to do. How to fight …

‘You’re making me laugh!’ chuckles Pavel Suvorov, our crew leader. ‘They must also cross the Don while it’s dark, and need time to get to the rear without the Nazis spotting them.’ Suvorov’s good-humoured crowing convinces me of one thing: the moment we jumped down here we became front line soldiers. And whatever happens in the time to come, no one will remember, or take into consideration, the fact that we are just former cadets fresh from an infantry school.

It is surprising how the instinct of self-preservation works in a man. It seems that everyone else experienced the same feelings as I did: but we can already hear the signallers calling, ‘This is “Breech-block”, can you hear me? Over!’ while battalion artillerymen drag cases of ammunition towards their cannon; and on the breastwork, machine-gunners install their Maxims. In our company the mortars are also ready for combat, and Fuat Khudaibergenov, along with myself (in Suvorov’s gun crew he is the charger and I, the gun-layer), have neatly arranged the shells next to our mortar. Since we have a war, everyone should try to be an efficient cog in the entire fighting mechanism. That’s the most important thing.

So now that the hands have done all the necessary stuff, one might have a look around. The trenches seem old, with battered edges: ‘This means that we have been here a long time,’ explains Nikolai Makarov from the neighbouring gun crew. All the gun crews in our company were formed in the military school. ‘Or they were taken from the Germans,’ objects Victor Kozlov. Both speak calmly, as though they have been fighting for ages. German flares keep darting into the sky, lighting the bottom of the trench, while machine-guns fire incessantly.

‘Afraid of our night attack?’ smiles Ivan Konski, and in his eyes, which shine for a moment in the pallid light, I catch an expression of confidence, which finally calms me down. Senior Lieutenant Buteiko, our company commander, has already sent someone to the observation post, and warns me that I should be ready to replace the man on duty at dawn.

‘Well, Mansur, are you hot now?’ asks the deputy commander of the company, Junior Political Instructor Fatkulla Khismatullin, in Tartar. He has come up to us along with the CO. Before the war Khismatullin was a history teacher, and he used to ask us to explain in detail where we were born and what we wanted to do in life. This was for a future book he planned to write. He translates his question into Russian, so Buteiko and the rest of the men can understand: ‘I’m asking him whether he is hot now!’ Everyone has a big laugh. The thing is, I was born in Siberia, and during the practice shoots collapsed several times in the Tashkent heat. I was even afraid they would discharge me. We remember how in the school, because of the salt and sweat, we had to wash our blouses daily, and they would tear at the seams every fortnight. How we dreamed: ‘Wish I was at the front!’

‘Here we are at the front!’ concludes Buteiko, looking at his watch. ‘Now don’t forget what you were taught …’ The experienced company commander, who was in this war right from the start, taught us, among other things, to use additional charges as often as possible in order to clean our mortar barrels of gunpowder remains. If a barrel is not clean, the shell inside moves more slowly and if, during a barrage, a shell is inserted before the preceding one is fired, it can cause an explosion inside the tube …

‘You can have a rest now,’ said Buteiko, and he and Khismatullin, bending down, move further along the trench. Sergei Lopunov immediately asks Fuat to give him a needle and a piece of string, while Victor Kozhevnikov demands a pencil and some paper. We know that our charger always has in his kit whatever one might need: needles, string, shoe-laces, buttons, scissors, a razor, Vaseline, soap, shoe-polish, a brush, iodine, bandages, etc. Fuat always likes to have everything in excellent order. And he is never idle. Even now, while we are busy remembering the past, he uses the spare time to repair the torn lining of his greatcoat, and examines the broken heel of Nikolai Makarov’...