![]()

Part 1

Collaborative Reading

Approaches to Reading in Crowded Digital Spaces

![]()

1

How Digital Writing and Design Can Sustain Reading, or Prezi Is Not Just for Presentations—Well, Now, Maybe It Is

Donna Qualley

We have all heard it. We may have even said it to ourselves and our students. Good readers make good writers. You must know how to read before you can write. Reading sustains writing in the same way that air sustains life. No air, no life. No reading, no writing. The idea that reading is foundational to writing seems pretty unshakeable—even when the research calls this relationship into question.

In her 2015 book, The Rise of Writing: New Directions in Mass Writing, Deborah Brandt makes the bold claim that writing is now conditioning how and why we read. And this “ascendancy of writing-based literacy create[s] tensions in a society whose institutions were organized around a reading-based literacy” (3). We have seen these tensions play out in the many books (and teacher anecdotes) lamenting the loss of deep, intensive, focused reading practices, supposedly brought on by the shift from print to digital technologies. In his oft-cited 2008 Atlantic article, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” Nicholas Carr bemoaned that with internet reading, “our ability to interpret texts, to make the rich mental connections that form when we read deeply and without distraction, remains largely disengaged.” And we have seen these tensions play out in our classrooms. Our own field’s “Citation Project” (see Howard, Serviss, and Rodrigue, 2010) reveals the challenges that students have in accurately reading, summarizing, and paraphrasing outside source material. One of the key findings of this research—that students typically quote from the first paragraphs or pages of a source—would seem to support the belief that students don’t read or can’t read or just won’t read in the careful, deliberate ways we expect.

But perhaps, suggests Brandt, people are reading in ways we don’t expect. Today, more people, especially in the workplace, are reading to support their habit of writing. In her 2014 essay, “Deep Writing: New Directions in Mass Literacy,” Brandt notes that there is a tendency for “routine reading” to take place “within acts of writing.” In other words, individuals, both inside and outside of school, may be showing “a loss of appetite” for reading on its own, for reading outside of the realms of writing (19). If Brandt’s observations have merit, and more reading is happening in the service of writing, then could writing—specifically, digital forms of writing—become a way to nourish and sustain certain kinds of reading? If I find myself discouraged by students’ reading practices, how might I devise ways to use digital writing and design to reengage them in reading? This is the question I posed for myself in the fall of 2016.

I regularly teach an upper-level course in literacy studies, which is part of our writing studies minor. Of all the writing studies courses I teach, this one is the most content heavy. Students read, view, and/or listen to a range of theoretical, narrative, and visual print and online texts. Almost all the reading will either be unfamiliar or contradict what students assume literacy is and what literacy does. To help students sustain their reading of all this new information about literacy, I designed a quarter-long digital curation and design project using Prezi. My aim was for students to gradually come to a more complex historical, cultural, social, political, and personal understanding of literacy. Over the years, I have experimented with different print and digital production projects to help students synthesize this material so that they can construct more robust understandings of what literacy is and what literacy does, but none have worked as successfully as I would have liked.

Why Prezi?

Although Prezi1 is typically used as a platform for formal presentations, it is also a good tool for personal information management, invention, and connection-making. Prezi does not lock users into a linear format like word processing does, and it’s easier to continuously move things into different shapes and configurations that enable users to visualize relationships between ideas. The blank and infinitely revisable screen allows users to put information anywhere on the Prezi canvas and rearrange it later using the Prezi tools (e.g., frames, shapes, colors, sizes, lines, symbols, fonts, and zooming and tilting capabilities) to highlight (or “code”) information into categories. It’s also easy to insert images, YouTubes, and website links. Prezi was the only digital site that I could find that offered users the opportunity to invent, arrange, and experiment with their own designs and linkages without relying on predetermined templates.

In her 2010 essay, “The Rise of the Template, The Fall of Design,” Kristin Arola shares her concerns about how the steady growth and use of templates in Web 2.0 technologies. When users “post within preformatted templates designed by the site’s creators,” they are prevented from making their own “purposeful choices and arrangements.” More importantly, templates separate form from content. (6). As Arola notes, “Even though we can choose a template … we are not producing design ourselves” (7). Using templates to teach writing is not new to the field. We are all aware of ubiquitous templates such as the five-paragraph essay and Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein’s set of “They Say, I Say” templates for teaching academic arguments.

Decisions about design choice and arrangement are obviously important rhetorical decisions for writers, but could these design decisions also be important for readers of both print and online texts as well? Certainly, the use of familiar template formats on the web can ease the burden of both excess of available information and access to that information by making certain forms of digital reading more efficient and speedy (such as foraging to see what is available), as Daniel Keller suggests in his book, Chasing Literacy: Reading and Writing in the Age of Acceleration. However, templates can work against readers who are trying to do or produce something with the information that they read. Relying on templates in the era of digital production can forestall invention and deter readers and writers from discovering new links and relationships between ideas. In order to use digital writing to sustain and deepen reading or to curate content in such a way that individual readers can readily make connections, they need a more flexible platform. I thought I had found this flexible platform in Prezi.

In the rest of this essay, I will first describe the project that I devised using Prezi—not as a presentation platform, but as a curation and connection-making affordance to sustain students’ reading (and rereading) throughout the course. I then offer a kind of cautionary tale about the dangers of relying on proprietary software before closing with a brief discussion of two students’ projects from the second time I taught this course.

The Prezi Literacy Curation Project

First, what do I mean by curation? A curator (cura from the Latin meaning “care”) is a “content specialist,” a person who gathers (or “aggregates”), organizes, and interprets information on a specific subject. Traditionally, curators were associated with heritage collections (galleries, museums, libraries, or archives). With the explosion of information on the internet and the rise of social media, digital, curators are in demand. These are people who select, organize, and bundle information into categories so it is easily accessible to others. But curation, which has been called an “emerging” twenty-first-century information literacy, can also serve as an aide for one’s own continuous learning.

How It Worked

For each of the assigned texts, students put information that struck them as interesting or important anywhere on their Prezi screens, either as they were reading or soon after they finished. Their content might include concepts, definitions, explanations, examples, memorable points, personal connections, questions, or other commentary. For some readings, students might include a lot of content and for other readings, not so much. They could group information into tentative clusters as they went along—or they could wait until they had collected information from several texts. With each reading, students frequently found themselves reorganizing earlier information as they encountered the new content, often adding ideas they had neglected or overlooked the first time or deleting stuff that seemed less useful or critical to them in hindsight. Or they simply chose to reconnect the “dots” into new configurations for aesthetic reasons. In every case, students’ initial bundles and categories changed over the quarter. See Appendix 1A for a version of this assignment.

Backtracking and Side Excursions

I have long touted the importance of building our reading and writing courses in spirals rather than linear progressions so that students return to earlier work from their (supposedly more informed) positions later in the course. In practice, this continual looping back hasn’t always cemented or deepened my students’ understanding of the course material as much as I anticipate it will. I finally realized I needed to make these loops and spirals explicit in the formal structure of the course and not simply a class assignment. If I simply asked my students to “reflect” on Q or re-read X from the position of Y (where Y might be a text, a concept, a theory, an activity, an experience), it was just too easy for them to engage in “pretend rereading” by doing a single fly by over the material. So, I wanted to try something different. On my course schedule, I set aside specific days for “Backtracking and Side Excursions.” On these days, students could “backtrack” through the reading we had done thus far to anchor the ideas more firmly in their minds or look for connections between readings. They could also take a side trip into one of the concepts or topics that they would have liked to have read more about. Canvas, my course LMS site, contained additional articles and videos for every required reading. These class days also gave me an opportunity to sit with each student in this 20-person class and make observations and answer their questions about their developing designs.

And because our class met in a computer lab, students always had access to their Prezis and could refer to them during our class discussions of the reading. Many students added information to their Prezis that emerged during our class discussions. The nice thing about being in the lab is that students could write a quick note on their Prezis in class and later, elaborate on it and decide where the information fit. I have never experienced students using their “class notes” so productively.

Seeing Other People’s Prezi Projects in Process

On the backtracking and side-excursion days, students also had the opportunity to see what information and how much information their colleagues included on their Prezis. They noticed the kinds of connections their peers were making between different concepts, and sometimes borrowed and copied each other’s ideas for arranging their information. For example, after seeing one student’s use of speech bubbles, speech bubbles began to emerge everywhere. The more experienced Prezi users offered tips and suggestions to the less experienced users.

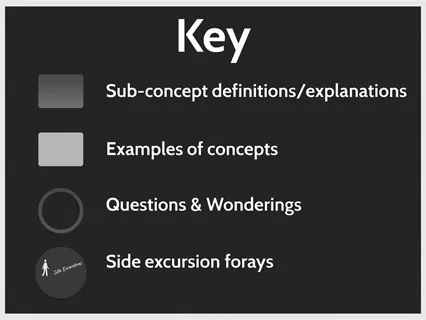

I should add that I also did this project along with my students. Initially, I shared strategies that I had stumbled across such as using the same color, shape, or symbol for similar forms of information (e.g., definitions, examples, questions, side excursions). Figure 1.1 illustrates the very simple key I devised for myself. It consisted of different colored rectangles for definitions/explanations and examples, circles for questions, and a walking figure encased in a colored circle for side excursions.

Figure 1.1 Donna’s Prezi key

Figure 1.2 Hanna’s Prezi key

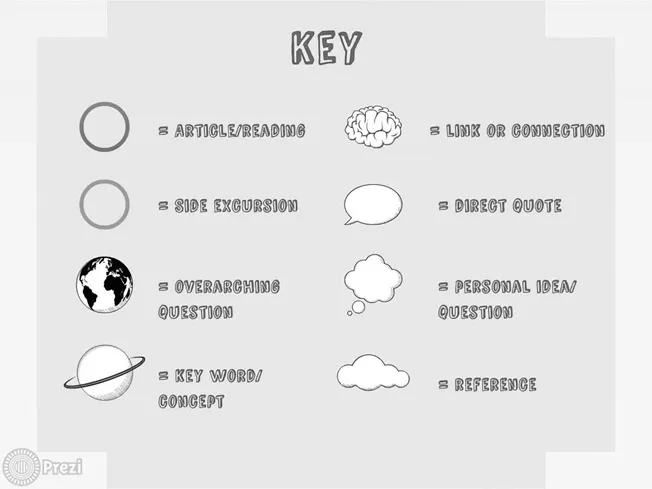

Figure 1.2 shows a more complex key that Hanna Hupp, one of the students in this course, developed. Hanna used different colored circles

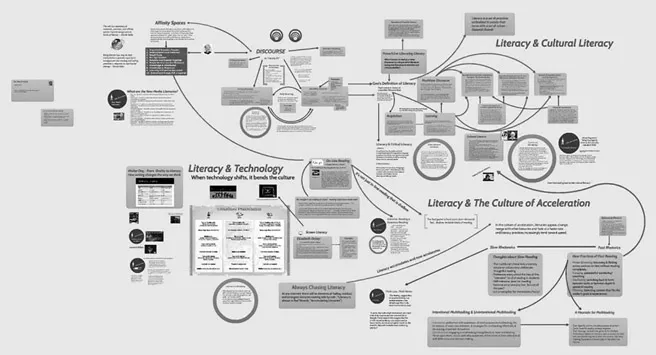

Figure 1.3 Donna’s week three version of Prezi

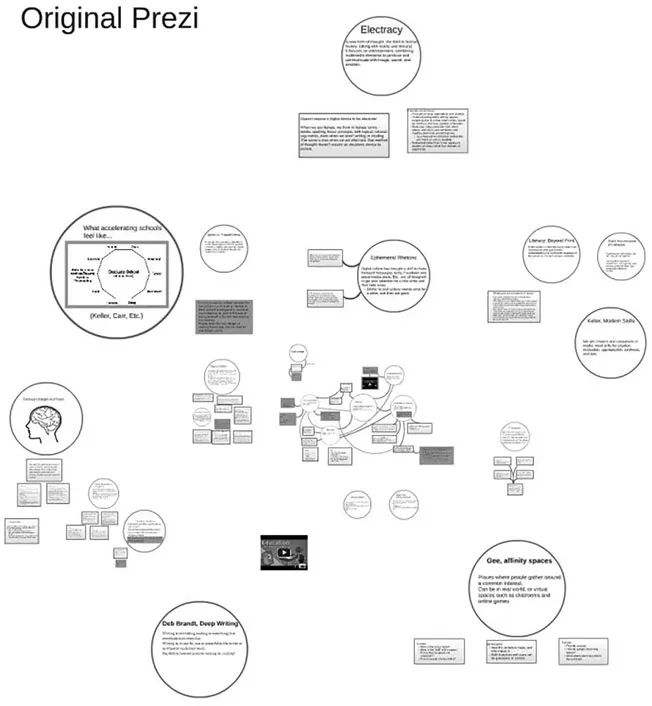

Figure 1.4 Donna’s week seven version of Prezi

for readings and side excursions and different kinds of speech bubbles for direct quotes and personal ideas and questions. She used images to show the connections she was making (a brain), her overarching questions (the world), and key words or concepts (a satellite).

I also made a copy of my early Prezi configurations so I could demonstrate how my initial “draft” was changing with the addition of new information. Figure 1.3 shows my beginning Prezi and Figure 1.4 shows a more elaborate, recategorized, and reconfigured Prezi. Figure 1.3 depicts my initial grouping and connection-making at the end of week three. The class had read two chapters from James Paul Gee’s Social Linguistics and Literacies, Richard Rodriguez’s chapter, “The Achievement of Desire,” from Hunger of Memory, and had just begun examining articles on cultural literacy. Figure 1.4 shows my more robust version of Prezi at the end of week seven. In addition to containing more information, my content has been reconfigured into four large categories: Discourse, Literacy and Cultural Literacy, Literacy and Technology, and Literacy and the Culture of Acceleration. I was beginning work on a fifth category, Affinity Spaces and the New Media Literacies. This Prezi now includes several side excursions, a few images, and some YouTube links in its path as well.

A Regenerative Remix

In many ways, this project works like a regenerative remix. Remix scholar Eduardo Navas defines a regenerative remix as the juxtaposition of “two or more elements that are constantly updated, meaning that they are designed to change according to data flow.” The remix continually “regenerates” because there is a need to continually re-aggregate and update materials in response to constant cultural change. (We might think about how a website, a blog, or Wikipedia works.) In this course, I wanted students to update their understanding of literacy with each new text that they encountered. But I needed a method to encourage this constant updating and Prezi proved to be pretty useful for the task.

Figure 1.5 Mercury’s original Prezi

Unlike a Wiki page, however, Prezi doesn’t archive...