This chapter clarifies the object of this study; since we are dealing with populism, this task is anything but obvious. It is essential to situate the chosen approach to populism within the burgeoning literature on the topic, which originates from different disciplines and relies on different concepts. What is populism, and how can its presence be measured in party manifestos? How is it possible to understand the relationship between populism and democracy, and how does this impact the possible explanatory models for its social acceptability?

Christoph Blocher in Switzerland, Luigi Di Maio in Italy, Nigel Farage in the United Kingdom, as well as Jean-Luc Mélenchon in France – despite being erratically positioned along the right – left and authoritarian – libertarian (or GAL – TAN) axes – share a common element: they articulate populist discourses. They express an ideology, a vision of the world, which on the one hand celebrates the common people as the only legitimate source of power and on the other hand represents the economic, cultural, and political elites as the enemy, a cancer of society, a clique of intrigues and corruption that must leave the stage to the vox populi. This logic entails that only the truly populist leaders and parties may redeem the common people and implement radical, direct, or simply legitimate forms of democracy.

Given the gargantuan variety of approaches to populism, however, the popular use of the term is often inaccurate or misleading: the misuse and abuse of the term have contributed to increase its aura as an elusive concept.1 Even inside academia there has been much tug-of-war around definitions and applications, and the impression is that since the seminal work of Ionescu and Gellner (1969), the fuzziness has done nothing but increase. Populism seemed to be like the Teumessian fox of Greek mythology, destined never to be caught. Since the 1960s, scholars have been baffled by the “chameleonic” nature and “conceptual slipperiness” of populism (Taggart 2000). Isaiah Berlin argued that studies about populism suffer from a “Cinderella complex”:

There exists a shoe – the word “populism” – for which somewhere exists a foot. There are all kinds of feet which it nearly fits, but we must not be trapped by these nearly fitting feet. The prince is always wandering about with the shoe; and somewhere, we feel sure, there awaits a limb called pure populism.2

The concept of populism has become increasingly present in the public debate also because of its slipperiness and adaptability to several contexts. It is erroneously used as a synonym for nationalism, anti-elitism, and chauvinism but also to denote simplistic or even vulgar political positions. Duncan McDonnell and Ben Stanley have coined the term “schmopulism” to describe the fact that “populism” has become a popular buzzword in media and academia alike.

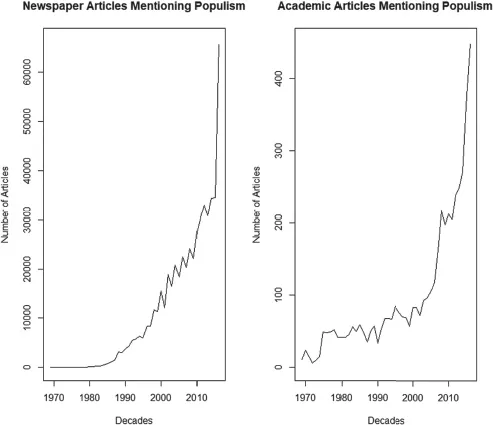

Figure 1.1 shows how scholars and journalists are talking about populism more than ever before.3 In newspaper articles (plot on the left), the term started gaining popularity in the 1990s, then it grew steadily; in just one year (between 2015 and 2016), the term became literally ubiquitous, with a jump from around 34,000 articles mentioning the term to more than 65,000 articles. The development in academic peer-reviewed journals is similar, although the term populism already appears in a significant number of articles since the 1970s. From the 2000s, the growth is considerable: from 57 articles in 1999 to 446 in 2016. This is just a rough measure that contributes to understanding the extent to which populism has become one of the most discussed topics both inside and outside academia in Western Europe.

Figure 1.1Populism in Newspaper Articles and Academic Journals

To avoid any conceptual slipperiness, and in order to adopt a clear theoretical framework, this study situates itself in a precise strand of literature which considers populism as an ideology – or a worldview – articulated discursively. This conceptualization has provided a theoretical and analytical toolbox which finally allows the study of populism in a consistent and comparative way. The next sections expose the extreme variability of populist discourses in order to grasp populism’s ideological essence and eventually propose a minimal definition, which will constitute the base for the operationalization and measurement of populism in Chapter 4. Next, the relationship between populism and liberal democracy, and which elements of the populist idea of power resonate with the fascist past, are clarified.

Populism in historical perspective

From a populist perspective, true democracy – the rule (krátos) of the people (demos) – exists only when the will of the common people is respected as sovereign.4 It follows that populism becomes successful especially because it promises to introduce (or restore) accountability and responsiveness by involving the people in the decision-making process, thus reviving the idea of direct democracy introduced in Ancient Athens 25 centuries ago.5 However, political structures such as the Greek poleis do not exist anymore, and direct democracy in the context of nation-states is not at stake (Dahl 1989).6

Several historical manifestations of modern populism across the world show that the centrality of the people is constantly evoked in times of rapid socio-economic and political developments which leave large portions of the population without a credible representation of their interests. Globalization and modernization constitute the two main triggers for the formation of a breeding ground for populism not only in the twenty-first century but throughout history. For example, both agrarian populism and anti-Catholic nativism in the nineteenth-century United States developed in times of socio-economic turmoil as a response to the profound socio-economic and cultural challenges of the time (Swank and Betz 2003). The Russian Narodniki7 – around the 1860s and 1870s – originated from similar socio-economic conditions: a group of intellectuals tried to convince the peasantry to fight an egalitarian struggle aiming at land redistribution, believing in the peasants’ inherent socialism (Pedler 1927).8

Völkish movements9 – which developed in nineteenth-century Germany as a mix of populism, Romantic Nationalism, and German folklore (Trägårdh 2002; Olsen 1999) – were the expression of an anti-modernity reaction to the Industrial Revolution. Kurlander (2002, 36) argues that, in order to survive, liberalism in Germany had to become völkish and eventually created the space for the emergence of National Socialism.10 Similarly, in Austria and France, at the end of the nineteenth century, right-wing populist actors such as Karl Lueger and Georges Ernest Boulanger became very popular.

Since the 1970s, populism has resurfaced in Europe in its right-wing, nativist form as a reaction to the New Left and to the de-industrialization process, focusing on issues positioned on the cultural axis of competition, such as immigration, crime, and nationalism. Parties such as the Front National in France, the Danish People’s Party, and the Vlaams Belang in Belgium mobilized disillusioned constituencies in opposition to the mainstream parties and the political, economic, and cultural elites while proposing an ethnocentric vision of the people. In the following years, many other populist parties with similar agendas emerged all over Europe, such as the Sweden Democrats, the United Kingdom Independence Party, and the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands. This is the most studied and best-documented wave of populism, and it generated such tremendous attention that it often overshadowed every other historical populist manifestation.11 As a result, extreme and radical right-wing populism became a (wrong and misleading) synonym for populism tout court.

More recently, increasing attention has been devoted also to left-wing populist movements and parties, such as Podemos in Spain and SYRIZA in Greece (Stavrakakis and Katsambekis 2014), or the Occupy movements (Pickerill 2015). These political experiences gained traction in the context of a protracted and generalized economic crisis by proposing to fight inequalities and corruption and to restore the sovereignty of the people vis-à-vis supranational economic institutions.

This far from exhaustive historical overview – which focuses mainly on Europe while ignoring many other populist manifestations in Asia, Latin America, and Africa – clarifies how heterogeneous populism can be and in how many different organizational and ideological ways it can be declined. The purpose was to illustrate the extreme variability of parties and movements articulating populist discourses in order to understand which is the lowest common denominator and therefore propose a minimal definition of populism which allows study of the phenomenon in a comparative and longitudinal way (Rooduijn 2014b).

Populism: its ideological dimension and a minimal definition

This study, in order to analyze the presence of populism in several countries over time, adopts the ideational approach proposed by Mudde (2004). This represents the best way to grasp the essence of a political phenomenon that varies so heavily over time and across countries. If the last section illustrated the populist phenomenon by exposing some of its manifold empirical manifestations, this section aims at re-composing the idea of populism by following the fil rouge which allows the identification of its ideological core.

Every populist manifestation in first place shares the same idea of power. Only at the second stage does it matter whether a particular manifestation of populism follows a right- or left-wing agenda, whether it is a bottom-up movement or a top-down project, whether it relies on a charismatic leader or not, whether it opposes or proposes certain policies, whether it stands in government or in opposition. The aim of this study is to understand the conditions triggering the social acceptability of populist discourses across eight West European countries, and for this purpose it is essential to identify a set of common elements that characterize every empirical and, in particular, discursive manifestation of populism.12

For this purpose, the ideational approach appears to be the most suitable and convincing.13 It defines populism as a particular ideology or worldview based on a Manichean distinction between the pure people and the corrupt elite. Since it entails a very narrow set of ideas, populism is often described as a thin-centred ideology.14 In order to gain political depth, thin-centred ideologies such as populism are most commonly combined with more developed political ideologies such as socialism, nativism, or liberalism, depending upon the specific socio-political context and the type of actor articulating them.15Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (2012, 12) claim that “in practice, populism is almost always combined with one or more other ideological features.” This study adopts the ideational approach and therefore identifies populism as a combination of people-centrism and anti-elitism. This leads to the following definition (Wirth et al. 2016, 15):16

Populism is a thin-centered ideology, which considers – in a Manichean outlook – society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and postulates unrestricted sovereignty of the people.

The ideational approach, compared to the other existing ones, presents a main advantage: since it conceives of populism as a set of ideas, it become possible to clearly assess whether an actor is articulating a populist discourse.17 Indeed, the populist ideology becomes measurable as soon as an actor articulates it discursively.18 It also overcomes the typical dichotomous classification of political actors and journalists as either populist or not. In fact, it reflects the spectrum of different levels and varieties of populist discourses (Deegan-Krause and Haughton 2009; Rooduijn, de Lange, and van der Brug 2014).

Moreover, the ideational approach makes it possible for scholars to study both ...