eBook - ePub

The Missile Crisis from a Cuban Perspective

Historical, Archaeological and Anthropological Reflections

Håkan Karlsson, Tomás Diez Acosta

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 158 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Missile Crisis from a Cuban Perspective

Historical, Archaeological and Anthropological Reflections

Håkan Karlsson, Tomás Diez Acosta

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Previous works on the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) have approached the topic from the point of view of the U.S. and its allies, while Cuban experiences have still not been sufficiently discussed. This book presents new aspects which have seldom – or never – been offered before, giving a detailed account of the crisis from a Cuban perspective. It also investigates the archaeological and anthropological aspects of the crisis, by exploring the tangible and intangible remains that still can be found on the former Soviet missile bases in the Cuban countryside, and through interviews which add a local, human dimension to the subject.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Missile Crisis from a Cuban Perspective un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Missile Crisis from a Cuban Perspective de Håkan Karlsson, Tomás Diez Acosta en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Geschichte y Weltgeschichte. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part I

The 1962 Missile Crisis

Historical Reflections

1 The Threat of a Direct U.S. Invasion of Cuba

The origin of the Missile Crisis was not the deployment of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba in October 1962, rather the principal reason can be found in the hostile and aggressive U.S. policy against Cuba since the very beginning of the Revolution in 1959.

After the U.S. defeat at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961, the Cuban government became aware of Washington’s policy objectives toward Cuba and how these were aimed at eliminating the socialist system. The conviction that the White House was seriously considering the military option of using its own armed forces in a direct invasion of the island prevailed. This view was corroborated in later months by the stepping up of internal subversive actions organized and directed by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA appropriated financial and technical resources for the organization of terrorist and sabotage actions against the new Cuban government and the orchestration of assassination plots against the main leaders of the Revolution. It also engaged in intense ideological and psychological warfare, the provision of material support to pockets of armed resistance acting in different rural areas of the country and the support of other counterrevolutionary activities.

In the conclusions of the investigations ordered by President John F. Kennedy to General Maxwell Taylor in order to clarify the causes of the failure at Playa Girón, the latter recommended:

In the light of the foregoing considerations, we are of the opinion that the preparation and execution of paramilitary operations such as Zapata are a form of Cold War action in which the country must be prepared to engage… . Such operations should be planned and executed by a governmental mechanism capable of bringing into play, in addition to military and covert techniques, all other political, economic, ideological and intelligence forces, which can contribute to its success. No such mechanism presently exists but should be created to plan, coordinate and further a national Cold War strategy capable of including paramilitary operations.1

On November 30 of the same year, President Kennedy authorized the creation of the Special Group Augmented (SGA) within the National Security Council, presided over by General Taylor and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to carry out what was then the biggest subversive operation ever implemented by the United States for the purpose of overthrowing a foreign government. This operation was given the code name MONGOOSE, thus fulfilling the recommendations to include the “Cuban case” in the American Cold War strategy, a policy that remains in place today. Cuba continues to be, now more than ever, a victim of this policy, which according to theoreticians and politicians, ended with the disintegration of the Socialist bloc in Eastern Europe. Operation Mongoose included all forms of possible aggression: economic blockade, political and diplomatic isolation, internal subversion, assassination of Cuban leaders (particularly Fidel Castro), psychological warfare, and finally, military invasion. It was the continuation of an undeclared war that the United States had been implementing against Cuba since the triumph of the Revolution in 1959.

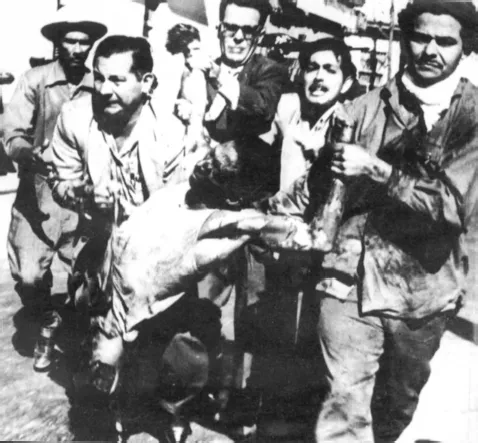

Figure 1.1 Sabotage of the steamship La Coubre, March 4, 1960. The ship that carried Belgian weapons meant for the Cuban armed forces was destroyed by two detonations when it was at a key location in the harbor of Havana. The sabotage claimed 101 deaths and 200 injuries.

Source: Archive of the Institute of Cuban History, Havana, used with permission.

It was not the first time that Cuba had denounced these aggressions. It is impossible to analyze the causes of the 1962 Missile Crisis without bearing in mind these factors, which are still part of U.S. policy toward Cuba. We will be citing excerpts from official U.S. government documents so that the dimensions of this conflict can be better understood. The preamble of “The Cuba Project,” the first guideline document drafted by the SGA working group, stated:

The U.S. objective is to help the Cubans overthrow the Communist regime from within the country and institute a new government, with which the U.S. can live in peace. Basically, the operation is to bring about the revolt of the Cuban people… . The revolt requires a strongly motivated political action movement established within Cuba, to generate the revolt, to give it direction towards the objective and to capitalize on the climactic moment. The political actions will be assisted by economic warfare to induce failure of the communist regime to supply Cuba’s economic needs, psychological operations to turn the peoples’ resentment increasingly against the regime, and military-type groups to give the popular movement an action arm for sabotage and armed resistance in support of political objectives. The popular movement will capitalize on this climactic moment by initiating an open revolt. Areas will be taken and held. If necessary, the popular movement will appeal for help to the free nations of the Western Hemisphere. The United States, if possible in concert with other Western Hemisphere nations, will then give open support to the Cuban peoples’ revolt. Such support will include military force, as necessary.2

Operation Mongoose included 32 tasks for various U.S. government departments and agencies and a timetable of activities, beginning in March 1962 and ending in October the same year with the defeat of the Cuban regime. The executive order signed by President Kennedy in March 1962 very clearly explained the aims pursued:

In undertaking to cause the overthrow of the target government, the U.S. will make maximum use of the indigenous resources, internal and external, but recognizes that final success will require decisive U.S. military intervention.3

Therefore, in March 1962, even when there were no missiles in Cuba and the USSR had not even made its proposal to the Cuban government, the U.S. government had already decided a priori that in October of that year a crisis of extraordinary dimensions would break out in the Caribbean, as it already intended to attack Cuba militarily. However, as history has shown, the Cubans would defend themselves, as they have done throughout all these years.

As is well known, the blockade against Cuba was signed off on in February of 1962 and Cuba was expelled from the Organization of American States (OAS) that same year as part of the anti-Cuban project. After that, a war of various dimensions was unleashed, which even included bacteriological attacks. From January to August of 1962, a total of 5,780 subversive actions were executed in Cuba, of which 716 were acts of sabotage aimed at important economic targets in the country.

An enormous spy and sabotage apparatus was established in Miami, which became the largest CIA operations base that has ever existed in North America. J. M. Wave, the code name of that abomination, aside from producing its own operations, coordinated actions against Cuba with CIA centers around the world. More than 400 case officers and nearly 4,000 agents worked on it, J. M. Wave had so many small boats and ships disguised as merchant marine vessels that it came to be considered the third largest navy in the western hemisphere.

Two plots were developed to defeat the Cuban revolutionary government, one of them in the month of May, before the Soviet delegation bearing the missile proposal had even arrived in Cuba. Dozens of CIA agents and counterrevolutionaries trained in the United States were infiltrated onto the island, loaded with weapons, explosives and war supplies aimed at preparing a “popular uprising” through the insurrection of the counterrevolutionary groups that were active in the country. The main leaders and agents were arrested in Cuba, and the magnitude of the conspiracy became evident. A Cuban State Security report noted that the objective of the United States was to subvert the country and defeat its government by all means, including a military invasion.4 It was therefore evident that the Cuban leadership had sufficient information regarding the U.S. plans when the Soviet delegation arrived in the country on May 29, 1962.

In August of that same year, another subversive plan was designed. On this occasion, the plan, which was backed by the Pentagon, was for a military invasion of Cuba to try once again to create a counterrevolutionary upheaval throughout the country. Hundreds of tons of weapons and dozens of CIA agents were again infiltrated into Cuba while, at the same time, a deceitful press campaign was waged in the United States and in other parts of Latin America. All this was in keeping with the SGA agreements of August 10, 1962, where the group decided to implement “Plan B plus,” which was a generalized plan to provoke an internal crisis in Cuba through subversive actions that would then pave the way for the military action. The plan failed and was denounced by Cuba before the rest of the world. However, U.S. actions continued to escalate and had acquired such dimensions that on September 17, 1962, the Foreign Affairs and Armed Services Committees of the U.S. Senate met to analyze the situation in Cuba and the projects presented to invade the country, invoking the Monroe Doctrine. Other subversive actions carried out by the United States in the context of Operation Mongoose included attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro and activities related to the ideological poisoning of the Cuban people by means of psychological warfare.

In April 1962, the ZR/RIFLE operation was launched, with the objective of eliminating the top Cuban leader, depriving the revolutionary government of its head. Several plans for such attempts were prepared, one of which became public in the United States years later when the Mafioso John Rosselli was seeking the support of the U.S. authorities in order to avoid extradition for his criminal activities.

Thus, a typical CIA operation was uncovered. If this had not happened, the United States would have never admitted it. The 1975 U.S. Senate Report, which investigated the CIA plots to assassinate foreign political leaders, noted that in early April 1962 William Harvey testified that he was acting on “explicit orders” from Richard Helms, the new deputy director of the CIA, when he requested Colonel Sheffield Edwards, the Agency’s Director of Security, to make contact with Rosselli. Through his subordinate, James O’Connell, Rosselli, the Mafia boss, was introduced, who gave an explanation about the possibilities of taking out a contract to kill Fidel Castro using his Cuban collaborators. The report states: “Harvey, the Support Chief [O’Connell] and Rosselli met for a second time in New York on April 8–9, 1962,” and it continues, revealing that “a notation made during this time in the archives of the Technical Services Division [of the CIA] indicates that four poison pills were given to the Support Chief on April 18, 1962.”5 Days later, on April 21, Harvey and Rosselli met in Miami. Harvey knew that Rosselli had contacted the same Cuban who had participated in the previous operation, on the eve of Bay of Pigs. Harvey “gave the pills to Rosselli,” the report continues, “explaining that these would work anywhere, at any time with anything.” Rosselli testified that he told Harvey that the Cubans intended to use the pills to assassinate Che Guevara, as well as Fidel and Raul Castro. According to Rosselli’s testimony, Harvey approved of the targets, stating, “everything they want to do is all right.”6

William Harvey was not just an ordinary employee or the “bad boy” of the CIA. He was in charge of Task Force W, the code name for the anti-Cuban task force. He had been appointed in January 1961 to lead the ZR/RIFLE program, which, as the U.S. Senate discovered for themselves, was tasked with assassinating foreign leaders that U.S. policy had deemed unsatisfactory.

For more than four decades, the CIA organized and supported projects to assassinate Fidel Castro as a basic premise for defeating the Cuban Revolution. To get an idea of the dimensions of this criminal endeavor, suffice it to refer to the more than 600 investigations of assassination plots against the revolutionary leader carried out by the Cuban security bodies during the cited period.

Psychological warfare has been and still is one of the essential weapons that the United States has used to defeat the Cuban government. Within Operation Mongoose, this activity acquired state dimensions. The director of the United States Information Agency (USIA) affirmed during the 1950s that the simple introduction of doubt in the minds of the people would in itself be a great success.

An idea of the scope of this aggression is provided in the released Mongoose documents. Among many other objectives, the following are outlined: creating a difficult climate, thus motivating forces to “free” Cuba; showing concern for Cuban refugees, especially orphaned children; highlighting the failure of the Cuban government to fulfill the promises made by the 26 of July Movement; depicting intolerable conditions in Cuba; and disseminating the fact that ordinary citizens and not only the wealthy were fleeing the country. The Mongoose documents also stated that the mass media should be used to employ all emotional means; to retake the ideology of Marti, making use of his memory to emphasize the distance between it and the communists; and to popularize songs through commercials dealing with these slogans. The documents noted that Mrs. Kennedy would be especially efficient in making visits to refugee children, as suggested by the impact recent visits of the presidents of Venezuela and Colombia to refugee camps, and called for the dissemination throughout the continent of documentaries, chronicles, cartoons, etc., all degrading the Cuban regime.7

This was the war that the United States launched against Cuba in 1962; it can be imagined how much blood, tears, casualties and economic damage Cuba has suffered for the right to defend its sovereignty and the right to choose its preferred social system. What right does a country have to launch a war of this nature against another nation, only because it does not accept its policy? It is therefore obvious that Operation Mongoose did not spring from “social” conversations, as many politicians and specialists in the United States have tried to have us believe in recent years. For all of these reasons, we believe that we cannot analyze the 1962 October Missile Crisis without bearing in mind that by then the United States had declared an open war against the government and the people of Cuba, while Cuba prepared itself from May of that same year to face military aggression by its powerful neighbor. That is also part of the historical truth. Mongoose was defeated, as has been acknowledged by its principle leaders. In his book Robert Kennedy and His Times, Arthur Schlesinger recalled:

In October of 1962, Robert Kennedy pointed out that, almost a year after Mongoose “there had been no acts of sabotage and even the one which had been attempted had failed twice.” The CIA complained during that same year “Policy makers not only shied away from the military intervention aspect but were generally apprehensive of sabotage proposals.”8

However, this affirmation does not correspond to the subversive actions that the CIA implemented during that period, and has validity only in relation to the fact that Mongoose did suffer numerous setbacks. Precisely during the Missile Crisis, the CIA was carrying out one of its most important sabot...