![]()

Introduction

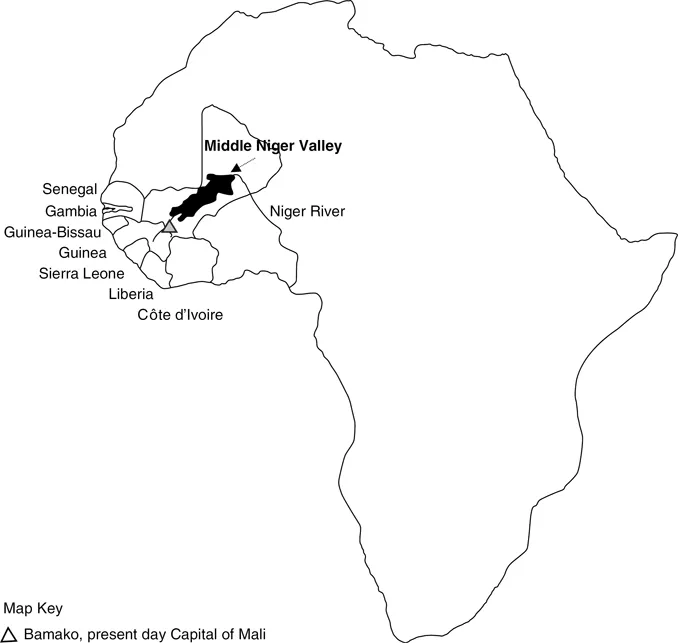

A profound understanding of traditional Mandinka dance systems requires knowledge of the origin of the culture and the people that produced it. Although the larger Mande-speaking language group contains myriad subgroups, only a small portion of those splinter groups is responsible for creating Mande culture as it is currently known. From the Middle Niger Valley to Ancient Ghana and the Mali Empire, the overwhelming influence of the Soninke, the Susu, and the Mandinka cannot be overlooked. Equally important are the political structures founded by the culture hero Sunjata Keita.1 Although many traditional cultural tenets were retained, Sunjata laid an entire system of prohibitions on top of them. As a result, the dynamics among artisan classes, other social groups, the larger society, and all accompanying dance systems were forever transformed.

Divisions and expansions occur within all groups. Artisan classes splintered into many from the original four. Informal internal tenets of age-grades and other social associations became more tangible and began to occupy a more centralized space within the group. The empire created by Sunjata spread west and southwest and brought with it the entire entourage of cultural tenets that were characteristic of the Mande in general and the Mandinka in particular. Hence, a Mandinka cultural diaspora was born. As a result, Sunjata’s mandates regarding dance systems were adhered to over an extensive area.

Mandinka influence did not die with the decline of the Mali Empire. Dependencies created as a result of Mali’s expansion became empires in their own right. The state of Kaabu rose to prominence, founded by Sunjata’s loyal general, Tiramaghan Traore. Its dominance over the entire southwestern region of Senegambia escalated after the decline of Mali. Thanks to the aforementioned accounts, Mandinka dances can be witnessed throughout a large portion of West Africa today.

Note

1Culture heroes are individuals credited with founding long-standing cultural and political tenets deemed significant by the constituency of a society. They can be found within the folklore and oral histories of societies throughout Africa. In this respect, Sunjata is similar to Shaka Zulu in South Africa, Simon Kimbangu of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and many others.

![]()

The Mande

Mandinka culture is a product of Mande-speaking people. To possess a sound understanding of the history of traditional Mandinka dance systems, one must obtain a basic knowledge of the history and culture of the people that produced them. Thus, the discussion of Mandinka dance systems must begin with the Mande. The land that the Mande ultimately dominated nearly a millennium ago has historically been referred to by many names. “Sudan” has long been a word associated with diverse parts of Africa. It translates from Arabic to “land of Black people” in English. The territory referred to as East Sudan is understood to be the political entities of Sudan and South Sudan, located in East Africa south of Egypt. The western portion of Africa that protrudes into the Atlantic Ocean, also the area discussed in this book, is known as Western Sudan. Before the political partitioning of Western Sudan by the process of European colonization, Western Sudan was also known as Senegambia. Precolonial Senegambia reflected the cultural cohesion of the area and included the territories of the modern-day countries of Guinea, Mali, Guinea-Bissau, Côte d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, in addition to Senegal and The Gambia. It is therefore referred to as Greater Senegambia by Africanist scholars. Sahel, Arabic for “coast” or “shore,” describes the area of land directly south of the Sahara Desert and north of the African rainforest. It stretches across the continent from West to East and encompasses Western Sudan and the Greater Senegambia region. Hence, in this study, the terms Western Sudan, West Sahel, and Greater Senegambia will be used interchangeably.

Mande is a language family that is part of the larger Niger-Congo language group. Linguists theorize that the group originated in East Africa in Sudan.1 Over the course of time, as a consequence of a continual process of environmental deterioration, and through myriad migrations, the Mande people began to inhabit large portions of West Africa. Initially, they resided in small groups based on lineage. However, in the third century BCE, an unusually large number of Mande and Fulani began to cluster around the valley of the Middle Niger River – located in the modern state of Mali (see Map 1.1).2 This society emerged in the Middle Niger Valley without the influence of the Arab or the Mediterranean world; it was a purely African phenomenon. The urban center that emerged organized itself into a heterarchy and formulated the foundation for the ancient Malian cities of Dia and Jenne-jeno.3 Artisans, cultivators, and merchants began to congregate in Jenne-jeno in circa 250 BCE. The networking systems employed by these groups facilitated specialization, but this was apparent in remote periods before the inception of the cities of Dia and Jenne-jenno. A corollary of specialized trade was that the trade networks and clientism became the glue that held the cities and villages together. Although the population was extensive – tens of thousands of people resided there – it was governed through the interdependence of its residents, which was facilitated by the activities of the artisan groups (especially the smiths), the cultivators, and the merchants.4

The significance of the artisans and cultivators cannot be overstressed. These groups were instrumental in creating and maintaining cohesion in early multiethnic noncentralized, and centralized states. They are also the focal point where a large number of Mandinka dances were conceived. To fully understand the culture that provided the foundation for Mandinka dances, the primary social groups from which they originated must be discussed.

Artisan classes

The artisan groups have been referred to as caste groups. Yet, they differ significantly from the more familiar castes of India. Although some artisan professions such as blacksmiths existed before centralized states, strict caste groups in Senegambia did not emerge as such until the Mali empire.5 Before Mali, the artisans were individual professionals with areas of specialization. Their crafts were transmitted through an apprentice system. One need not be related to the master artisan in order to become his/her apprentice. All artisan groups formed their own secret societies and they each generated their own dances.

Artisans traveled from household to residence, from village to town, and they also frequented marketplaces. They simultaneously overlaid a cultural blanket over all areas they came into contact with. This cultural drape embraced and emphasized similarities between the Mandinka, the various other Mande daughter-groups (see Table 1.1), and other ethnicities it touched.6 Thus, at the points in history when the ethnic groups dispersed from the Middle Niger Valley, they brought with them a common culture along with their distinctive cultural tenets. As a result, inhabitants from the Middle Niger Valley all contained specialized artisan groups or guilds, within their societal structures. The numbers and types of artisan guilds multiplied and varied from Mandinka to Tukulor, and from Wolof to Fulani, but the role that the artisans played in their societies were identical and were undeniably of Mandinka origin.7

Table 1.1Classification of Mande-Speaking People (Abridged)

| Mandinka | Soninke | Susu (Soso) | Songhay | Nono |

| Bambara | Jula | Vai | Bozo | Mende |

| Khassanke | Koranko | Kono | Jogo | Ligbi |

| Numu | Atumfuor | Wela | Jeri | Yalunka |

| Kpelle | Looma | Bandi | Loko | Sorogama |

| Tieyaxo | Sarakolle | Hainyaxo | Bobo | Dzuun |

| Sembla | Jo | Mano | Dan | Tura |

| Guro | Yaure | Mwa | Wan | Gban |

| Bgen | Bisa | Sane | Samogo-Tougan | Maya |

| San | Maka | Busa (Bisa) | Boko | Shanga |

Dance earmarked all momentous events, and it was intimately tied to the various duties and activities of the artisan guilds. The blacksmiths, jalis, woodworkers, and so on all had their own particular dance repertories.8 The historical order of appearance of the artisan guilds are: blacksmiths, jalis, leatherworkers, and last, Islamic praise singers. The latter group was included in the artisan social classes after the introduction of Islam. The blacksmiths are considered to be the oldest of the professional artisans and were one of the groups that held the Middle Niger Valley civilizations together.9 Nonetheless, it was the ability to wield Nyama that facilitated all of the artisans in their endeavors.

Nyama is the fo...