![]()

1

Beginnings

![]()

Beginnings

Musicals are like children. They are conceived out of an act of excitement, the pregnancy is long, frustrating and rewarding, birth can be very painful, raising them is an act of collaboration with many people, and, if you are very lucky, they will support you in your old age.

Writing a musical, like a pregnancy, will take your care and attention, it will often be demanding, it will fill you with love and it might even put a strain on your other relationships. It will tie you to the people you created it with for ever. But once you have created a musical, it will always be part of your life, and you should always be proud of it.

This book is, therefore, a prenatal guide for musicals. It will help you generate ideas to conceive your show, make sure that the skeleton is all in place and healthy, help you fill out the flesh and bones of the characters and help you finally see it born onstage in a living, breathing performance. It also has a section on how to put it to work and make it earn its living.

As the title suggests, this book also examines how musicals work. It looks at the storytelling and structure of some well-known musicals, and shows how the best musicals draw on ancient myths and tap into the human psyche to engage the audience. You cannot create great art until you understand how that art has been created in the past, even if you then work in your own idiosyncratic manner.

Like the creation of all arts, it is easy to write a bad musical. Some bad musicals even get produced and some of those shows even become hits. A bad painting can be walked past, bad novels can be put down, but bad theatre must be endured (at least for its running time!).

Shoddy work, ill-considered decisions and a lack of craft will generally mean that the work will not take its rank among those shows that are often revived. A true classic, like Sondheim’s Into the Woods, or Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!, will have a long and successful life. This book looks at how successful musicals work, gives an indication as to why some musicals fail and considers the ways in which writers can ensure that their musical will be as good as possible. It can help you understand how the musical you want to write can have truth and depth, and how it might be more likely that people will want to produce and perform your musical for a long time to come.

Writing a musical is 10 per cent inspiration and 90 per cent perspiration. It is a lot of hard work. This book is full of the techniques that I use to write, developed through working as a professional writer of musicals and plays, from my work as a theatre director, from working as a dramaturg for Mercury Musical Developments, and from teaching the creation of musical theatre for the University of London.

Exercises

Throughout this book you will find shaded boxes like this one. Each box contains an exercise that is designed to stimulate ideas and to make you really think about the musical you are writing. Do whichever of them interest you, but at least read them and consider the point of each of them. You might find it helpful to buy a copy of a libretto for a musical that you like, as some of the exercises involve analysing existing musicals. If you do them all, you will have enough ideas to last you a lifetime.

Before starting you should think about the type of musical you want to write and about what your distinctive, original voice will be. I often read musicals that are derivative of other works. It is no good setting out to write like Sondheim, Lloyd Webber or Jason Robert Brown: those three have already mastered those styles. You need to think about who you want to be as a writer. The techniques can be taught, but the combining of the techniques with your own unique talents is something that only you can do. Some of the biggest hits of recent years like Matilda, Avenue Q, Spring Awakening and In the Heights have come from writers who understand the art form, but have combined it with a distinctive voice. It is time to find yours.

What is a Musical?

For the purposes of this book, I define a musical as a theatrical presentation where the content of the story is communicated through speech, music and movement in an integrated fashion to create a unified whole. The written work is formed of three elements, the book, the music and the lyrics. The book is sometimes known as the script, and is the unsung sections of the work; the lyrics are the words that are sung. The book also refers to the character development and the dramatic structure of the work; together, the book and lyrics are called the libretto, which is Italian for little book. The music and lyrics together are referred to as the score.

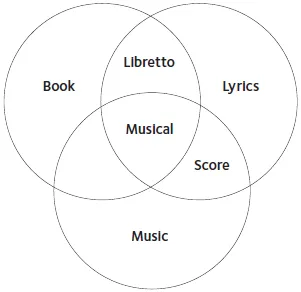

The following diagram shows how the different terms relate to each other and overlap:

You will note that there is no word for the book and music together. Music that comes under spoken scenes is referred to as ‘underscore’, as it comes ‘under’ the dialogue at a level at which the audience can still hear and understand what is being said.

Why Write a Musical?

The fact that you are reading this book probably means that you are interested in writing a musical, but have you taken a second to ask yourself, ‘Why?’

For some, there is a love of the art form. The best musical performances feature ‘triple-threat’ performers who can sing, dance and act to a highly professional level, who can remain convincingly in character when combining all their skills and who can perform work that is thought-provoking, exciting, moving and stimulating. Along with opera, it is the most theatrical art form, and can deliver some stories better than any other. It is removed from real life yet capable of acting as a prism to it, transporting an audience to see sights and hear sounds they never imagined.

For some, the attraction is financial. The musical is the most commercial form of theatre. Broadway box-office income tops $1 billion every year, and this means that something in the region of $45 million of royalties is split between the writers of the twenty or so Broadway musicals playing at any time. That is before you take into account the national tours, the West End transfers and other overseas productions. If a writer of a musical mega-hit ever offers to buy you a drink, then let him because he can afford it. And if he ever offers to buy you a house, he can probably afford that too.

For some, the attraction is fame. Rodgers and Hammerstein, Andrew Lloyd Webber and George Gershwin are well-known names and this kind of recognition lights some people’s fires.

For me, the attraction is creative. I write musicals because I love the form. I love being able to tell a story in a truly theatrical fashion, and to be able to elevate the emotional content through song and dance. Musicals are often criticised for being unrealistic, that people do not suddenly burst into song and dance in real life. I live real life every day, and for me the attraction of the musical is its theatricality. I don’t want to go to the theatre to see the ordinary everyday; I want to go for an elevated, emotional experience where a performer is able to connect with an audience using all the skills they possess.

And, for me, writing musicals is simply the best fun I ever have.

Collaborators

There is a good chance that you are going to write a musical with a collaborator. A few successful writers manage book, music and lyrics all by themselves; Lionel Bart for Oliver! and Sandy Wilson for The Boyfriend have done so, but these are the exceptions rather than the rules. Most musicals are written by more than one person, and choosing your collaborators is one of the most important decisions you will make.

Depending on which parts of the musical you want to write, you will need to find a collaborator or collaborators to undertake the remaining work. You need to define how you see yourself:

Bookwriter: Writes only the book, but none of the sung components (e.g. Arthur Laurents for West Side Story and Gypsy).

Librettist: Writes the libretto, i.e. the book and lyrics (e.g. Oscar Hammerstein II for Oklahoma! and Carousel).

Lyricist: Writes only the lyrics (e.g. Stephen Sondheim for West Side Story or Oscar Hammerstein II for The Sound of Music).

Composer: Writes only the music (e.g. Leonard Bernstein for West Side Story or Richard Rodgers for Oklahoma!).

Composer-Lyricist or Songwriter: Writes both music and lyrics (e.g. Stephen Sondheim for Follies or A Little Night Music).

Think about your talents, what you are good at and which parts of the musical you want to write. Having defined your role, by deciding which part of the process you want to be responsible for, you should easily be able to define the talents you need in your collaborators.

You may already have a potential collaborator in mind, and you must begin a collaboration for the right reasons, not the wrong ones. The right reasons are that you like and respect their work, they like and respect your work, and that you think you are temperamentally suited to one another. A good collaboration is like a good marriage; a bad one, like a bad marriage, is a disaster. A good one is based on mutual trust and respect; a bad one can send you into emotional meltdown. If you are working with a friend, ensure that you like and respect their work. You don’t want to wreck a good friendship writing a bad show!

If you know you want a collaborator but don’t have an individual in mind, then finding one can be a tricky task. Some organisations, like Mercury Musical Developments, offer the opportunity to advertise for one, and theatres that produce new writing may know of other writers looking for collaborators.

A good collaborator will let you have the space to do your best work, kindly point out when you haven’t, and can do better, give you the space to fail, and support you when you are wrestling with a tricky problem. You should do the same for them.

You might end up with more than one collaborator. It is not uncommon for musicals to have three writers, one each for book, music and lyrics. Three-way relationships can sometimes be difficult, and you should treat each partner equally.

Having found someone you think you want to write with, then try the collaboration out on a very small project. Suggest to your collaborator(s) that you try out your relationship by writing a song, or a very short musical. As part of the course that I teach at the University of London, the students have to write a fifteen-minute musical, using a cast of no more than four actors and accompanied by nothing more than a piano. I usually give them a broad theme to write around, and these pieces are then performed in very limited productions for an audience of fellow students. A project like this can be an excellent way to assess your relationship with your collaborators. Alternatively, if both you and your collaborator(s) have written songs or scenes previously, then listen to or read each other’s work, and then spend ten minutes talking about things you liked about it, and things you didn’t like, or weren’t sure about.

Sharing Work

Share some of your previous work with your collaborators and then talk about the three things you thought were best about the work and the three things you thought were least successful. By doing this you can begin to establish a relationship where you can be honest and constructively critical.

Collaborator relationships vary as much as the people in them. Some writing teams have incredibly close personal relationships, some see each other only at meetings. Gilbert and Sullivan had a famously strained working relationship in which Gilbert would frequently write the entire libretto without consulting Sullivan, who would then compose the mu...