![]()

Levels of Infinity

(1930)

Mathematics is the science of the infinite. The great achievement of the Greeks was to have made the tension between the finite and the infinite fruitful for the knowledge of reality. The feeling of the calm and unquestioning acknowledgement of the infinite belongs to the Orient, but for the East it remained a mere abstract awareness that left the concrete manifold of existence lying indifferently to one side, unshaped and impervious. Coming out of the Orient, the religious feeling of the infinite, the apeiron, took possession of the Greek soul in the Dionysian-Orphic epoch that preceded the Persian Wars. Here the Persian Wars also mark the release of the Occident from the Orient.1 That tension and its overcoming became for the Greeks the driving motive of knowledge. But every synthesis, as soon as it was achieved, permitted the old antithesis to break out anew in deepened form. Thus, it determined the history of theoretical knowledge into our time. Indeed, today we are compelled everywhere in the foundations of mathematics to return directly to the Greeks.

Anaxagoras was the first to give the concept of the infinite a formulation that allowed it to play a role in science. A fragment that has come down to us from him says: “In the small there is no smallest, but there is always a smaller. For what is can by no division, however far it is carried out, ever cease to be.” This concerns space or body. The continuum, he says, cannot be put together out of discrete elements, which would be “chopped off from each other as if by an axe.”2 Space is not only infinite in the sense that nowhere within it does one come to an end, but at every place it is, so to speak, infinite in the inward direction. A point may be more and more exactly fixed only through a process of division extending to infinity, from level to level. This stands in contrast with the calm, completed existence of space for intuition. For the quality that fills it, space is the principle of separation, is that which makes possible the variability of the qualitative, but also is separation and, at the same time, contact, continual coherence, so that no piece may be “chopped off, as if by an axe,” from another. Therefore no actual spatial thing can ever be adequately given because it unfolds its “inner horizon” in a process of ever newer and more precise experiences that unfolds to infinity.3 Thereby it appears impossible through any such process to posit the actual thing as existent, closed and completed in itself. So the problem of the continuum drives one to epistemological idealism: Leibniz, among others, testified that the search for an exit from the “labyrinth of the continuum” first led him to the conception of space and time as orderings of the phenomena. “From the fact that body does not permit itself to be dissolved mathematically into primary ‘fundamental moments’ [‘indivisibles’] it follows immediately,” said Leibniz, “that it [body] is nothing substantial, but rather an ideal construction, which denotes only a possibility of parts, but certainly nothing real.”

Against Anaxagoras arose the strict atomism of Democritus, one of whose arguments against the limitless divisibility of bodies runs something like this: “It is said that division is possible; very well, let it have happened. What remains? No bodies, for these could be further divided and their division would not have come to an end. Only points could remain, and body would have to consist of points, which is clearly absurd.” The impossibility of grasping the continuum as a fixed being cannot be more powerfully illustrated than by the well-known paradox of Zeno about the race between Achilles and the tortoise. You know what it consists of: Assume that the tortoise has a head start of length 1 on Achilles; if Achilles is twice as fast as the tortoise, then at the moment when Achilles arrives where the tortoise started, the tortoise will be a distance

ahead; after Achilles has covered this ground, the tortoise has gone a journey of length

; and so forth ad infinitum; hence it follows that swift-footed Achilles never catches up with the the reptile. The hint that the successive partial sums of the series

do not grow beyond all bounds but converge upon 2 —a hint by which today one may think to resolve the paradox — is certainly an important, relevant, and illuminating remark. But if the distance of length 2 actually consists of infinitely many partial distances of length

as “chopped off” wholes, then Achilles exhausting them all is contrary to the essence of infinity as “unfinishable.” Hence Aristotle remarks on the solution of Zeno’s paradox that “what is moved does not move by counting,” or, more precisely, “when you divide the continuous line in two halves, you take the one [dividing] point for two; you make it both the beginning and the end. In dividing thus, neither the line nor the motion remains continuous. . . . In the continuous, there are indeed infinitely many halves, but they are not actually but

potentially.” Since Leibniz gives phenomena a foundation in a world of absolute substances, he too cannot evade Democritus’s compelling argument and conceives the idea of the monad. “In the ideal or the continuum,” said Leibniz in agreement with Aristotle, “the whole precedes the parts . . . The parts are here only potential. In substantial things, however, the simple precedes the aggregate; the parts are actual and given before the whole. These reflections eliminate the difficulties regarding the continuum, difficulties that only arise when one sees the continuum as something real, which, prior to any division on our side, in itself possesses actual parts, and when one holds

matter to be a substance.”

The key word given here to solve the antinomy of the continuum is the distinction between actuality and potentiality, between Being and Possibility. Accordingly, in the end, the unfolding of the mathematical construction of reality rests on its subjective-objective double nature: it rests on the fact that it is not a being in itself, but rather an appearance for an intellectual I [ein geistiges Ich].4 If, metaphysically, with Plato, one lets the picture that hovers before consciousness arise from the meeting of a “movement” from the I and one from the object, then one will make the I responsible for extension, the intuitional form of space and time, as the qualitatively undifferentiated field of free possibilities.5 Mathematics is not the stiff and paralyzing schema the layman prefers to imagine; rather, with mathematics we stand precisely at that intersection of bondage and freedom that is the essence of the human itself.

If we now set ourselves to grasp these old ideas somewhat more precisely, we discover infinity first not in the continuum but instead in a still more primitive form in the sequence of natural numbers 1,2,3, . . . ; only with their help can we approach at all the mathematical grasp of the continuum. In the development of arithmetic, as far as the role of infinity is concerned, four levels can be distinguished. To the first level belong such individual concrete judgments as 3 > 2; the number-sign // is a partial piece contained in the number-sign ///. To the second level belongs (for instance) the idea of <, of “being contained” for arbitrary number-signs and the judgment of hypothetical universality: given any two number-signs A, B, then either A < B, A = B, or, finally, B < A. The domain of the actually given is not exceeded here because this judgment only pronounces upon cases in which determinate numbers A, B are given. Something wholly new occurs, however, when at the third level I locate the actually occurring number-signs in the sequence of all possible numbers arising through a process of generation in accord with the principle that from a given number n, there can always be generated a new one, the next number, n′. Here the existent is projected onto the background of the possible, of an ordered manifold of possibilities producible according to a fixed procedure and open to infinity. Systematically, this standpoint is expressed in the definition and proof by complete induction: To establish that a property P belonging to some arbitrary natural number n belongs to every such number, it is enough to show that (a) 1 has the property P, (b) if n is any number with property P, then the next number n also has property P. The distinction between even and odd numbers by the familiar “counting off by twos” is a simple example of definition through complete induction, which can be reduced to the form: (a) 1 is odd; (b) depending on whether n is even or odd, then n′ is odd or even.6

The general propositions of number theory at this level concern the freedom of a self-developing sequence of numbers to stop at an arbitrary place. The transition to authentic theoretical knowledge is thereby accomplished: the transition from the description a posteriori of the actually given to the construction a priori of the possible, in whose manifold the given is assigned its ordered place not on the basis of descriptive features, but on the basis of the results of certain mental or physical manipulations and reactions to be carried out on it, for example the counting process. The foes of this method are on the one hand the empiricists (because a priori construction is a thorn in their flesh), who fondly imagine they can grasp Being as a single layer, unadorned, “by pure description” (Bacon contra Galileo, Hume contra Kant, Mach contra Einstein).7 On the other hand there are the metaphysicians, who, out of hatred for freedom or for the field of construction insofar as it is open to infinity, build up a stiff dialectical concept-world as true Being (Hegel contra Newton). — We will only later address in more detail the fourth level of arithmetic, in which according to the model of the Platonic theory of ideas the Possible is turned into a transcendent and absolute Being, which is by nature inaccessible in its totality to open-eyed [schauenden] insight. For now, we will refrain from this dangerous step and turn from the natural numbers to the continuum, asking how we are to describe this substrate of possible divisions that proliferate ad infinitum.

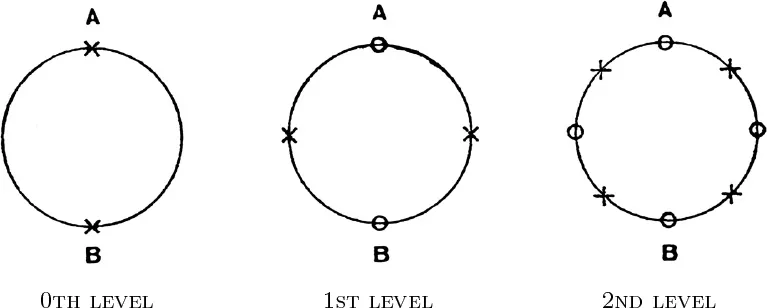

As an example, I choose the one-dimensional closed continuum, say the perimeter of a circle. Let it first be divided into two pieces or arcs that border each other at their ends, A, B (the zeroth-level division). For the transition to the first-level division, each of these arcs is divided into two parts; for the second level, the same thing is repeated with each of the four sub-arcs that have thus arisen, etc. The number of arcs is multiplied by 2 at every step. (See the figure, in which the new divisions for every level are marked by crosses.)

In the succession of divisions for the zeroth, first, second, . . . , nth, . . . levels, the infinite series of numbers emerges. I would gladly stipulate that at every level the pieces that arose at the previous one are exactly halved, but I may not. For it is of the essence of the continuum that (1) it is divisible, yet (2) it is not divisible exactly (has no parts “chopped off from each other by an axe”), though (3) the fineness and precision of the division need nowhere find a limit at which to cease. Hence, successive divisions can only be carried out with a certain imprecision; but while the division proceeds from level to level, those vaguely determined limits established by the earlier divisions must become more and more precisely fixed. It is senseless to imagine that this process, which is virtually infinite, could have reached its end in an actual continuum; rather, it has always only reached a certain level. But we must keep the possibility open that the process can be taken a step further at every level. Hence, we separate the “arithmetically empty form [Leerform]” of the process of division from its actualization in a given continuum; the description of the empty form consists in specifying how the pieces (designated by appropriate symbols) of the nth level border one another and which of these pieces arise out of which pieces of the previous level by the nth division. The empty form, in contrast to its concrete realization, is defined a priori to infinity. The mathematical theory of the continuum is about this empty form. — We already know another arithmetically empty form: the sequence of numbers. Something undivided gets divided into one piece (the 1), now kept as a unit, leaving an undivided remainder; this remainder is divided again into a piece (2...