![]()

Part I

Practices of Participation and Citizenship

![]()

1 (New) Forms of Digital Participation? Toward a Resource Model of Adolescents’ Digital Engagement

Annika Schreiter, Sven Jöckel and Klaus Kamps

Resources for Political Engagement

A growing body of literature on the use of online media (boyd 2014; Kupferschmitt 2015; Lenhart et al. 2015; Livingstone et al. 2015; Livingston and Sefton-Green 2016) paints a rather straightforward picture of how young people turn to online media regarding political questions. Online participation or even seeking online for information surrounding politics in general accounts only for a very small part of the online activities of adolescents. We wonder why this should be the case and – to address this book’s title – whether this finding is not due to a specific form of misunderstanding new forms of political engagement and participation.

The possible answers to these two questions are ambivalent. One answer might quite simply be that adolescents use social media and acquire meanings from their ‘convergent media ecology’ unevenly (Mascheroni 2013). They may not see a specific sense in using the internet in the political realm – even though the options of online participation, information, empowerment and organisation are vast and manifold and the hopes for new models of democratisation are accordingly high (Rheingold 2000). Another (potential) answer might be that in terms of political participation we tend to analyse things with regard only to classic categories such as following traditional news media or debating politics offline (Bennett 2008). Therefore, we ask, how, why and under which circumstances adolescents become involved with politics online (up to the point where they factually participate and initiate in political debates). These questions will be addressed in this chapter. In other words, instead of complaining about the marginal share of politics in the ‘online world’ of adolescents, we focus on the resources used (and their specific contexts) when (new) forms of political engagement effectively occur. Therefore, our general research question reads: What resources may explain the political online engagement of (German) adolescents? For the purpose of this chapter we concentrate on the results of the last study out of a series of three conducted in Germany from 2011 to 2013.

An Engaged Youth Perspective

Our normative approach to the phenomenon of digital participation is a participatory perspective on democracy. It views engagement in politics and the community in general as the backbone of a thriving society. Citizens are seen (and compelled) as active members of a political association in which they are not only interested but also obliged to enhance and influence it in many different ways. The more the members of a society participate and the wider the variety of their activities, the better for the community (Barber 1984; Putnam 1993). Following this perspective, a similar view is taken on adolescents. Bennett (2008) describes two different ways in which – roughly speaking – the participation of young people is seen. First, the disengaged youth paradigm, the decline of voter turnouts and other traditional forms of participation are seen as a threat to democracy. Adolescents are described as widely detached from politics and society. Nontraditional forms of participation like ethical boycotts or digital participation are seen as less important – or are even left out of the equation. Even when adolescents rally on the streets – mostly organised through social media – this is often not seen as political but as deviant, as danah boyd (2014, 207) outlines for the case of the high-school student protests against immigration laws in 2006. By contrast, the engaged youth paradigm focuses on new forms of (digital) participation: “[…] [T]his paradigm emphasizes the empowerment of youth as expressive individuals and symbolically frees young people to make their own creative choices” (Bennett 2008, 3). At the same time, the need for traditional forms of participation such as voting as a core act of representative democracies is diminished (Bennett 2008; Bennett et al. 2009). In this chapter, we follow the engaged youth paradigm but hold a critical view on the balance between creative, as well as new forms of participation and the need for citizens that participate on an institutional level and in traditional ways.

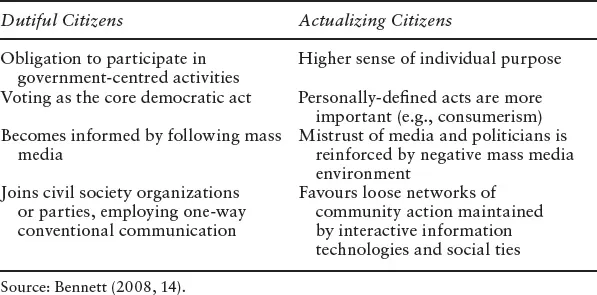

Bennett (2008) further describes a change in citizenship itself. He argues that on the one hand there still exists a traditional citizen type, the so-called dutiful citizen. These citizens think of participation as their political obligation and prefer traditional, government-centred forms such as voting or joining civil organisations or political parties. They follow the mass media and have a profound trust in governmental organisations, politicians and most of the media. In contrast, on the other hand, actualizing citizens are generally wary of these. They prefer topic-centred, creative forms of participation organised in loose (digital) networks. They do participate; not out of a feeling of duty but because they prefer to in another context or because of a specific subject (Table 1.1).

These two types of citizen are just a rather broad depiction of a subtle shift in citizenship. They are by no means selective, and they are not exclusively separating ‘younger’ and ‘older’ citizens. Of course, a lot of adults participating as actualizing citizens and adolescents can belong to the dutiful type (Bennett et al. 2009, 106–107). But this differentiation helps to outline the difficulties in describing digital participation in terms of a political idea or even a theory based on dutiful citizens alone.

Table 1.1 Typology of Citizens

The concept of actualizing citizens explains how young people become engaged in politics and why they might be sceptical of traditional forms of participation. However, it does not explain whether and why they actually participate. This question stands in a long tradition of research (Milbrath 1965; Verba and Nie 1972). In addition, the specific question of how political participation may evolve in adolescence has also been of major interest (Norris 2003; Ogris and Westphal 2006; Albero-Andrés et al. 2009; Quintelier 2015), and more recently also with a focus on digital participation (Bakker and de Vrees 2011; Lim and Golan 2011; Rauschenbach et al. 2011; Spaiser 2012; Wagner 2014). Again, most of these studies simply describe different forms of (digital) participation but not how the antecedents and constraints of political participation may be explained. In this chapter, we employ and propose a resource-based approach to fill this gap. This approach is based on the standard socioeconomic model of participation (Verba and Nie 1972), which assumes that participation is influenced by socioeconomic factors like demographic attributes, financial resources, education and individual factors (such as a sense of democratic duty or self-efficiency). This model describes a politically active elite which is mainly male, middle-aged, highly educated and with high income (Verba and Nie 1972, 13–14; Brady et al. 1995, 271; Leighly 1995, 183–184). Brady et al. (1995) specified this model to a resource-based approach in which participation is explained by the resources time, money and civic skills like rhetorical or interpersonal skills. These skills are acquired during childhood and adolescence, but may be further developed in adulthood, for example, through civic engagement, which stands in close relation to political participation.

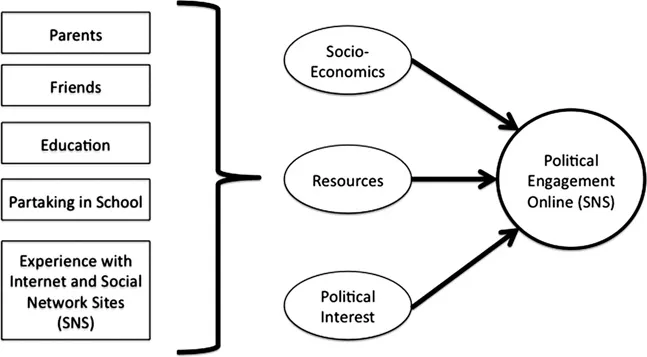

We see political participation as a special form of civic engagement concerning political processes and decisions. Civic engagement has a broader meaning and is comprised of activities like doing work for the local community. Following Ekman and Amnå (2012, 289–292), political participation comprises more manifest forms of activity that directly aim at influencing political decisions. Civic engagement, on the other hand, is a latent individual and collective form of action aimed at influencing circumstances in society outside the direct personal surroundings, for example, voluntary work for the local community (Figure 1.1).

Drawing upon this approach, we related those resources to adolescence and to online engagement. First, we eliminated the resources time and money. Adolescents’ time is highly structured by activities they cannot influence such as school or their parents’ wishes. It may also be questioned whether one can obtain valid answers to the question, “How much free time do you have?” The availability of money depends partly on the income of parents but also on educational choices (e.g., Feil 2004, 38–39). In addition, the German Shell Youth Study of 2015 shows that money-related activities like donating are hardly carried out by adolescents (Schneekloth 2015). Civic skills, in contrast, are mainly acquired during adolescence via the main agents of political socialisation: education and partaking in school, peers and families (Brady et al. 1995; Jenkins 2009; Quintelier 2015). We therefore consider them as the resources of young people for political participation; and because our focus lies on engagement online, we also added experience with online media and social network sites (SNS) as a resource for digital engagement. This is based on the results of several studies indicating that people who frequently use the internet also tend to use it more for political purposes (Bakker and de Vreese 2011; Emmer et al. 2011; Spaiser 2012; Quintelier 2015). Sociodemographic variables and general political interest as a key resource are understood as additional ways of explaining digital participation.

Pre-studies and Developing a Measure of Political Participation on SNS

This study is the third in a series of three. For the purpose of this chapter, we focus on the last analysis but will briefly summarise the previous two in order to introduce our method. The first study was a paper-and-pencil questionnaire (February 2012) on forms of online engagement. We included six forms of online participation, derived from a major youth study in Germany titled ‘Aufwachsen in Deutschland’ (AID:A) [Growing up in Germany1], including taking part in a flash mob, a mail bombing or signing an online petition (Gaiser and Gille 2012). In addition, we asked for seven social network forms of engagement2 (e.g., writing a statement in an online discussion or following a political party in a social network; Jöckel et al. 2014). Following Ekman and Amnå (2012), these forms lie in between political participation and civic engagement. They do not really aim at influencing political processes or decisions, but are still connected to the political sphere and potentially influence it. This study consisted of 452 German students (10–18 years, Mage = 12.65, SD = 1.73, 54% female).

The second study was a qualitative interview study on adolescents’ perspectives on politics. Fourteen students from different school types in Germany, all aged 16 or 17 years, were interviewed about their perspectives on politics, (online) participation and their media use (Potz 2014).

In both studies it became evident that – in line with the results of the AID:A study – most forms of online participation are hardly carried out. Between 5% and 10% of the participants had at least once used one of those forms. We further found that about one tenth of the participants had no knowledge of such activities. In contrast, especially low-level forms of social media activities, like taking part in an online discussion, were used more often – up to 35% of the participants had used them at least once and they were far better known as well (Jöckel et al. 2014, 156). As a consequence of these findings, we ask for forms of online participation that are known to adolescents and far more connected to their everyday online and social media behaviour. We subsequently reconstructed our measure of political participation online and used the broader term of political engagement online in the following chapter, which includes participation in a strict sense but also low-level forms on SNS that cannot be accounted for as political participation, but still have a connection to the political sphere like following a political Facebook page. It is of course debatable to what extent we might view these forms as engagement and not merely as practices of political communication. As online engagement is prone to low-level forms, which can be described as ‘micro-activism’ or ‘sub-activism’, we view it as a first step into more action-oriented and more complex forms of engagement and even participation (c.f. Bakardjieva 2009; Marichal 2010; Ekmann and Amnå 2012).

Following recent approaches on the development of political online engagement (Emmer et al. 2011), we distinguished three crucial aspects that may be carried out in and through the use of SNS. On the basic level (1), SNS are a tool to convey political information. Political news is shared online through Facebook and Twitter. For adolescents, SNS might become vital news platforms and complement news from traditional journalistic platforms (Wagner 2014). Yet, it is an inherent feature of SNS that political news (2) is not only consumed but often enough also commented. Again, this resembles the offline world, only that discussions are now no longer taking place in the ‘salon’, the proverbial political arena of deliberative democracy, but in online forums and SNS. Thus ‘information’ is considered to be the first and perhaps fundamental function of political participation on SNS, which is then followed by ‘discussion’.

As a final consequence (3), participation, in a strict sense, is described as the final form of engagement online: This includes becoming active on SNS, for example, founding a political group to inspire others.

Based on our two pre-studies, we came up with a measure of these three forms of political engagement on SNS: Information, Discussion and Participation.

Our Main Study – Method and Procedure

The main study was conducted in late 2012/early 2013. We had access to all students from a German high school in the same area in which our two pre-studies had already been conducted. Again, we carried out a paper-pencil survey in classroom contexts. We interviewed all students that used SNS. Out of a total of 473, we identified 329 students that used SNS, resulting in mostly younger students (grades 5 and 6) being screened out. Our sample ranged from 10 to 20 years of age and 52% of participating students were female. Average age was 15 years (SD = 2.25). We employed a standardised questionnaire with some questions identical with study 1, but our main measures – as mentioned above – were newly constructed for this study.

We specified our main research question and asked: What resources can explain political engagement of adolescents on SNS? For this, we relied (1) on a broad range of measures for adolescents’ resources as described above and (2) our three types of political engagement on SNS: Information, Discussion and Participation. The latter became our dependent variables, while the resources acted as independent measures.

Based on the resource model of political participation we included sociodemographic variables (age, gender) as controls but were basically interested in the impact of the civic skills. In this chapter, we first looked at political interest as one underlining factor whose impact has been shown in many di...