Reflective Window

One might like to believe that musical notation is a glass window, through which those of us on the outside see into the study of the composer’s intentions, experience the sounds exactly as they were imagined. The twentieth century, however, taught us that notation is not a neutral code, that the process of writing affects what is written. Moreover, if the light outside were to dim and the crowd go away, then the window might begin to reflect back the composer’s own image, and the incursion of notation into the process of composition become inescapable.1

This book addresses a silent aporia in landscape architecture discourse, the paucity of design tools to adequately address landscape’s inherent temporality and seeks to investigate new notations for landscape architecture through a synthesis with music notation. It accepts the assertion of English composer Cornelius Cardew (1936–1981) that ‘notation and composition determine each other’,2 and in investigating music notation provides a reflective window through which to consider new ways of conceiving, understanding, and constructing landscape. The Hungarian composer György Ligeti (1923–2006) presciently noted that ‘one often arrives at something qualitatively new by uniting two already known but separate domains’,3 the approach taken in this book, which draws directly and conceptually from music, the discipline with the longest and broadest history of notating time. Casting light onto both landscape architecture and music, as though we are standing between two mirrors, allows us to reflect on both. In a form of infinite recursion we see each field reflected in the other, a reciprocal study examined through the shared prism of notation. This reciprocal relationship can curiously be traced back to the earliest history of the development of Western Art music notation. Called in Latin in campo aperto, ‘in an open field’, it referred to the non-diastematic method of providing mnemonic prompts to singers of ecclesiastical music, drawing the first connotation between the temporality of music and landscape.

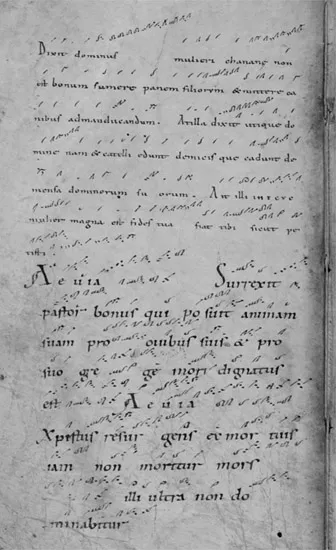

1.1 Extract from the Cantatorium of St Gall, an example of in campo aperto notation, and the oldest surviving complete music manuscript of neume notation. This form of non-diastematic notation was without horizontal stave lines and, consequently, a means of accurately representing relative pitch. 922–925. Courtesy of St Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 359: Cantatorium, f. 4v (http://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0359 ).

Made by Walking

The long history of this book was inspired by two encounters, separated by 23 years. Firstly, my interest in landscape lies in the experience of a seminal year spent in Canada when I was 12 years old. Considered by my father to be still too young for drinking and driving, he instead bought me a gun. I wandered hours and days, passing weeks and months through the forests of northern Ontario near our lake shore cottage, a vastness undefinable by a sense of dimensional space. It was actually the duration of the walks that gave a sense of scale to the landscape, and the thousands of trees that provided its visual and auditory experience. As English landscape architect James Corner recognises, we perceive landscape through ‘the accumulation of often distracted events and every day encounters’.4 This was certainly the case for me and this walking experience gave me the confidence to get lost, to enjoy the unexpected, and to understand that time is the builder. As the Spanish poet Antonio Machado (1875–1939) reminds us, ‘there are no paths, paths are made by walking’,5 and like those old walks I took in Canada, this book grew out of an exploratory journey, examining aspects of music and landscape architecture along the way.

Secondly, I was inspired by the discovery of American musicologist Thomas S. Reed’s Directory of Music Notation Proposals6 in 1997, a compendium of over 500 new music notations developed in the latter twentieth century. Subject to some inevitable repetition, this study showed the rich possibilities of reinvestigating an existing notational language, which instinctively one might presume to have become fully developed, and rigidly fixed. The implication of Reed’s publication on landscape architecture seemed profound. If such variety of new forms of notation could be created through a detailed study of alternative modes of representation in music, then surely similar possibilities must also exist for landscape architecture, which like music, is conceived and constructed through drawing, and which like music, is centrally located around time.

Everything Under the Sky

The word landscape, having both practical and philosophical dimensions, has never easily been defined by a single etymological strand. Derived from the Dutch word landschap referring to units of agrarian or enclosed land, a more widely understood connotation has come from its extensive use in art, such as the Venetian painter Giovanni Bellini’s (1459–1516) Saint Jerome Reading in a Landscape from 1485. This painting shows a landscape progression from Saint Jerome in his wilderness sanctuary reading from the Bible with the mythical lion at his feet, towering rock formations, to a distant walled city. This landscape is not a natural construct, but synthesised from stylised and allegorical references.

The interconnectedness between different aspects of landscape’s meaning has a long history but by the early eighteenth century notions of landscape encompassed three ideas that were to have longstanding resonance. Reference to each of these can be found in a single series of articles on the pleasures of imagination written in the summer of 1712 by the founder of The Spectator, Englishman Joseph Addison (1672–1719). Firstly, that landscape was constructed through vision. Building upon English philosopher John Locke’s (1632–1704) notion of a sensory hierarchy, Addison noted that ‘our sight is the most perfect and most delightful of all our senses. […] It is this sense which furnishes the imagination with its ideas; so that by the pleasures of the imagination […] I hear mean such as arise from visual objects’.7 Secondly, that landscape is a mental construct as much as a physical realm. Addison noted that the sensory delight he spoke of arose ‘either when we actually have them in our view, or when we call up their ideas into our minds by painting, statues, descriptions, or any the like occasion’.8 He went on to state that the ability to picture in our imagination is so strong that ‘a man in a dungeon is capable of entertaining himself with scenes and landscapes more beautiful than any that can be found in the whole compass of nature’.9 Thirdly, that landscape was not nature but was constructed and this could be achieved through the active manipulation of the world around us. He wrote that:

fields of corn make a pleasant Prospect and if the Walks were a little taken care of that lie between them, if the natural embroidery of the Meadows were helpt and improved by some small Additions of Art, and the Several Rows of Hedges set off by Trees and Flowers that the soil was capable of receiving, a Man might make a pretty Landskip of his own possessions.10

Later, the English novelist and politician Horace Walpole (1717–1797), writing in 1752, wonderfully described the designer of Rousham Gardens in Oxfordshire, Englishman William Kent (1685–1748), as ‘the inventor of an art that realises painting, and improves nature’.11 More recently, in 2012, architects Davide Deriu and Krystallia Kamvasinou noted that:

whether we look at professional fields such as landscape architecture […] or, more generally, at the place of landscape in the wider realm of architectural and urban cultures, […] the ways of seeing and representing the landscape are inextricably bound up with design practices.12

This book refers to three aspects of landscape, which are respectively termed: landscape space, both natural and manmade external spaces, defined by American landscape architect Kathryn Gustafson as ‘everything under the sky’;13 landscape art, the representation of external space in painting and other artistic media; and landscape architecture,14 a term first used by English designer J.C. Loudon in 1840 in reference to the works of English landscape architect Humphry Repton (1752–1818), albeit in connection with buildings, and which is now the recognised professional term for the design of external spaces. While focusing on landscape architecture this book necessarily also draws upon aspects of landscape art, and upon landscape space.

Music in this research uses the definition of English musicologist John Blacking (1928–1990) from 1973 as ‘humanly organised sound’, the title of the first chapter of his book How Musical is Man.15 Blacking’s definition, broader than the Oxford English Dictionary’s of music as ‘the art or science of combining vocal or instrumental sounds to produce beauty of form, harmony, melody, rhythm, expressive content’,16 creates more open possibilities to examine parallel aspects of music and landscape architecture than a narrower definition might provide. Also, except where otherwise noted, in Chapter 5 titled Meadows, the term music in this research explicitly refers to Western Art music. This is the musical culture where the writing of sounds has the longest and richest history with records dating back to 830 A.D., and where the notation of musical sound has been instrumental in its changing conception and development. I do not include the study of folk music as its history is often un-notated. Nor do I include jazz improvisations where the notation indicates the structural framework of chord progressions, although American landscape architect Walter J. Hood has referred to this in his writings17 and urban design projects.18 Also excluded is tablature notation, which is used not in the description of sounds, but to describe the manner of their production.