![]()

1 The Competitive Advantage of Nations

This chapter introduces the concepts contained in The Competitive Advantage of Nations. In the first section, the two main contributions of Porter’s (1990) book, the diamond framework and the model of economic development, are summarised. The next section contains a description of those applications of the diamond framework that are relevant to the Greek case. The third section encompasses the various views expressed on particular issues in Porter’s (1990) work.

The Competitive Advantage of Nations: The Diamond Framework and The Competitive Development of National Economies

The Diamond Framework

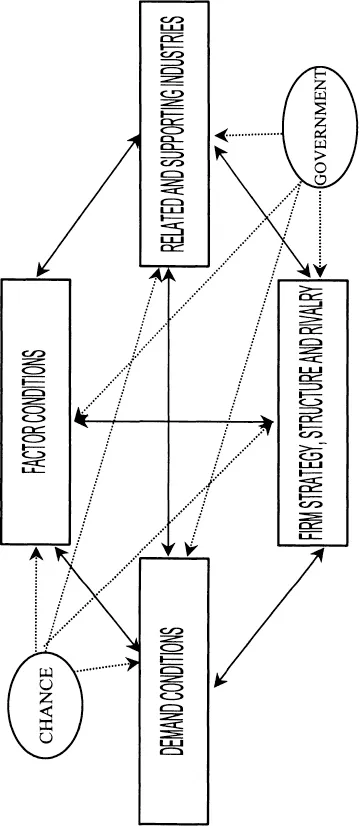

The main goal of Porter’s work was to determine the attributes of the national environment, which influence the competitive advantage of firms, in particular industries or segments. The result was the well-known ‘diamond framework’ (Porter, 1990: 71–130), where four groups of determinants - factor conditions, demand conditions, related and supporting industries, and firm strategy, structure and rivalry - individually and through their interactions promote or hinder the creation and sustainability of competitive advantage for industries within a nation. There are also two additional determinants - government and chance -shaping the national environment in an indirect way, that is, working through the other four determinants, as can be seen in Figure 1.1.

Factor conditions The first determinant consists of the production factors necessary for an industry. Porter favours a detailed classification, including human resources, physical resources, knowledge resources, capital resources and infrastructure. Competitive advantage stems from possessing low-cost or high-quality factors, efficiently and effectively deployed.

Factors can be categorised as basic and advanced. Basic factors, that include climate, location, unskilled and semiskilled labour, etc., are essentially inherited or created through simple, unsophisticated investment. Advanced factors, such as a digital data communications infrastructure, university research institutes, etc., are much harder to create, demanding large and continuous investment and often the presence of appropriate institutional structures.

Figure 1.1 Porter’s Diamond Framework

Source: Porter, 1990:127.

Another categorisation is between generalised factors that can be used by many industries (such as the highway system) and specialised factors that are specific to an industry or a limited group of industries (for example, narrowly skilled personnel). Specialised factors offer a more sustainable advantage for an industry than generalised factors. The presence, however, of these specialised factors usually requires an appropriate level of generalised factors.

Competitive advantage can also be gained by selective factor disadvantages. Faced with disadvantages in particular factors, industries are forced to innovate in order to improve their competitive position. In the process, new technologies and new ways to use or circumvent specific factors, emerge, which often provide the industry with a more sustainable advantage. Nevertheless, the condition of the other diamond determinants affects the ability of the industry to instigate the necessary processes.

Demand conditions The second determinant is demand conditions, and refers to the nature of home demand for the industry’s products or services. Porter (1990) identifies three major attributes of home demand as essential. The first one is the home demand composition, that is, the segment structure relative to world demand and the sophistication of the home buyers. Segment structure is important because ‘a nation’s firms are likely to gain competitive advantage in global segments that represent a large or highly visible share of home demand but account for a less significant share in other nations’ (Porter, 1990: 87). Customer sophistication is also essential, as demanding buyers pressure firms to meet the highest standards, and consumer needs that anticipate global trends stimulate innovation.

The second attribute is the home demand’s size and pattern of growth. Absolute home market size is important only in some industries or segments, where, for instance, production economies of scale are present or R&D requirements are high. A rapid growth rate, especially in periods of technological change, the presence of a number of independent buyers or an anticipatory early demand, can positively affect a much wider range of industries. Early or abrupt saturation in the home market can also be a source of advantage as firms are forced to compete on low prices, improved product features, and innovative products, or expand to foreign markets.

Internationalisation of home demand is the third attribute. This refers to mobile or multinational buyers that use products from their home base, and demonstrate to other firms the benefits of entering a foreign market. Additionally, internationalisation of home demand can be a result of various influences on foreign needs and perceptions of a country’s products that are acquired by foreign nationals when travelling, working or training in the home country or are transmitted through historical, political and cultural ties.

These three demand attributes reinforce each other and their importance differs according to the evolutionary stage of the home industry. Firms are always affected by the nature of their home demand as they pay greater attention, understand better and respond quicker to the needs of their domestic market.

Related and supporting industries The presence in a nation of related and supporting industries, is the third determinant that shapes competitive advantage. These industries can be suppliers to the competitive downstream industries, offering efficient, early and, although less often, preferential access to certain inputs. They are also a source of early and accurate information sometimes through informal networks, which are facilitated by the cultural proximity. However, the suppliers must be internationally competitive, or ‘strong by world standards’ (Porter, 1990: 104) if they are not competing globally, for these exchanges to be beneficial.

Moreover, an industry can benefit from the presence, in its home base, of other competitive industries with which it is linked through, among others, common inputs, technologies or distribution channels. Again, the relative ease of information exchange, that sometimes even results in formal alliances, enables firms to share these activities and benefit from each other’s innovations. Nevertheless, an industry can source its inputs from abroad, form alliances with foreign firms and achieve some of the benefits of having competitive domestic related and supporting industries.

Firm strategy, structure and rivalry The fourth and broader determinant includes the strategy and structure of firms in the domestic industry, as well as the rivalry among them. The firms’ strategies and structures, including aspects such as management practices, modes of organisation, willingness to compete globally, company goals, etc., must be appropriate for the industry in which the firms are competing. The way firms are organised and managed is affected by national conditions, such as the educational system, and historical trends. National firms succeed in industries where the required characteristics match the country’s prevailing organisation structures as well as in those ‘where there is unusual commitment and effort’ (Porter, 1990: 110).

The pattern of home rivalry is also considered by Porter as one of the major attributes that shapes competitive advantage. Competing firms pressure each other to improve and innovate, and domestic competition is more visible than competition from foreign firms. Moreover, domestic rivalry can be emotional or personal, as pride drives managers to be more sensitive towards domestic competitors, leading to better products or exports, since there are no excuses and ‘unfair advantages’, that are often cited as the reasons behind the success of foreign companies. Sometimes, rivalry can also lead to the upgrading of competitive advantage, as simple advantages, like basic factors or local suppliers, are not sustainable against other domestic competitors.

The formation of new businesses is also an important part of this determinant because it increases the number of competitors. The intensity of domestic rivalry, however, does not depend only on the number of competitors. Their commitment to the industry and the lack of extensive co-operation among the competitors are much more important. Porter even concedes that ‘a completely open market along with extremely global strategies can partially substitute for the lack of domestic rivals in a smaller nation’ (Porter, 1990: 121).

The role of government Government influences competitive advantage by an array of policies that affect all the other four determinants. Regulation, education, tax and monetary policy are examples of government’s impact on the competitive environment of firms. The role of government, however, is partial, according to Porter (1990: 128), as government policy can confer an advantage only by reinforcing the other four determinants. Its role can be positive or negative, and policies are usually affected by the national attributes forming the diamond.

The role of chance Chance events, i.e. occurrences usually outside the power of firms, also play an important role, usually by creating discontinuities that allow shifts in competitive position. These events, which include inventions, wars, natural disasters, sudden rises in input prices, surges of demand, and political decisions by foreign governments, among others, have a diverse impact on industries of different countries. The way national firms exploit the advantages, or circumvent the disadvantages, is determined by the condition of the diamond determinants.

The dynamic nature of the diamond The determinants of national advantage reinforce each other, creating a dynamic system where the cause and effect of individual determinants become blurred and competitive advantage depends on the entire ‘diamond’ system. Porter, however, states that not all the determinants are necessary to succeed in international competition, as a disadvantage in one determinant can be overcome by ‘unusual advantage in others’ (Porter, 1990: 145). His only emphatic assertion is that competitive advantage in more sophisticated industries rarely results from a single determinant.

Porter (1990: 143) also considers domestic rivalry as having a very direct role in helping firms ‘reap the benefits of the other determinants’. He also connects domestic rivalry with another very important feature of competitive industries, geographic concentration. A large number of industries studied by Porter (1990, 1998b, see also Enright, 1990) were based in small regions or even in individual cities within countries, and, in a few European cases, in adjacent regions of different countries. Proximity increases the concentration of information and the speed of its flow, raises the visibility of competitor behaviour and attracts the necessary factors and resources.

Another finding of Porter’s (1990) study is the presence of groups of successful industries in every nation. This finding led him to develop his ‘cluster charts’ which are described in detail in Chapter 2. Clusters of related industries, with constant interchanges among them, work in ways similar to the geographic concentration (in fact, those two phenomena often coincide). Accelerated factor creation, increased information flows, spreading rivalry and a tendency for resources to move away from isolated industries, and into the clustered ones, are all observations made by Porter (1990) in several cases.

The Competitive Development of National Economies

Porter (1990), in the ‘Nations’ part of his book, describes the pattern and evolution of industrial success in eight of the ten nations he studied. Using the data gathered during his project, he attempts to extend the framework, in order to assess ‘how entire national economies progress in competitive terms’ (Porter, 1990: 543). Linking the upgrading of an economy with the position of firms exposed in international competition, Porter (1990: 545–573) identifies four stages of economic development for a country: factor-driven, investment-driven, innovation-driven and wealth-driven.

Countries, in particular points in time, belong to the stage of development that corresponds to the predominant pattern in the nature of competitive advantage of their firms. Although these stages do not fully explain a nation’s development process, they can highlight the attributes of a nation’s industries that are most closely related to economic prosperity.

In the factor-driven stage, advantage for virtually all internationally competitive industries results from basic factors, usually natural resources, climate, land conditions and semiskilled labour. Indigenous firms compete essentially on price, in industries where technology is not required, or is widely available. Domestic demand for exported goods is modest and the economy is sensitive to world economic cycles and exchange rates. The range of industries may widen over time, with the creation of domestically-oriented industries through import substitution. However, these industries usually lack international competitiveness.

The investment-driven stage is characterised by the willingness and ability of the private and public sectors to invest aggressively. Firms construct modern facilities and acquire product technology from abroad. They are able to absorb the foreign technology and improve on it, refining the production processes to suit their particular needs. Firms, citizens and the government also invest in modern infrastructures, education and other mechanisms, which create advanced factors. Firms’ strategy and structure, as well as the increasing number of home rivals are additional sources of advantage for domestic industries. Demand is growing, even for exported goods, but sophistication is still low, while related and supporting industries are largely underdeveloped. The government’s role can be substantial at this stage with, for example, capital aids and temporary protection measures.

The innovation-driven stage is where all the diamond determinants are at work. The nation is competitive in a wide array of industries, with deeper clusters and even the establishment of entirely new groups of industries. Sophisticated service industries also develop because of knowledgeable and demanding customers and the presence of skilled human resources and infrastructure. Firms create technology, production methods and innovative products, and compete in more differentiated segments, on the basis of their high productivity. Global strategies emerge, as firms develop their own international marketing and distribution networks, usually depending on their established brand names. Foreign direct investment also increases with the relocation of certain activities to nations with more favourable endowments in particular factors. Industries are less vulnerable to price shocks and exchange rate movements in the world markets. Also, the national economy is less dependant on a few sectors. Government’s role becomes more indirect, with emphasis on improving advanced factors and the quality of home demand and preserving domestic rivalry.

The wealth-driven stage is where firms in a nation start to lose competitive advantage in many industries with intense international competition. Rivalry decreases as firms are interested in preserving their established positions, there is less motivation to invest and constant calls to the government to protect the status quo. Rising wages with slower productivity increases, mergers and acquisitions that seek to preserve stability, and reduced willingness to take risks, especially in starting new businesses or transforming existing industries, diminish the international competitiveness of many of the nation’s industries. This causes a declustering process, where the loss of position of one industry affects all the others in its cluster. The range of industries, where a nation can still compete, narrows to those that are related to personal wealth, basic factors and those where no technological changes occur or where the nation still has strong brand names.

Returning to the ten nations from which his main observations are drawn, Porter (1990: 565–573) categorises them according to their stage of development. Singapore is still considered to be in the factor-driven stage, while Korea has moved to the investment-driven stage. Denmark in the 1960s, Japan in the 1970s, Italy in the 1980s and Sweden soon after the war, reached the innovation-driven stage where they now are. Germany, Switzerland and the USA had reached this stage even before the Second World War. Porter (1990: 570–572) sees elements of the wealth-driven stage developing in the last three countries, while the UK is viewed as having been in that stage for decades now. Nevertheless, recent productivity gains and other developments in the UK are considered by Porter (1990: 573) as signs of an impending reversal, which is still not certain.

Applications of the Diamond Framework

The first applications of the diamond framework are essentially presented in The Competitive Advantage of Nations. Porter (1990: 277–541) devotes three chapters to study, in more detail, eight of the ten nations included in his original research. Although these applications can by no means be considered a test of the theory, as these are the countries providing the empirical observations for its inception, a brief summary can provide interesting insights on the way the framework can be applied. Particular emphasis will be placed on the European nations studied by Porter (1990) and especially Switzerland and Sweden, two countries with small home markets, Italy, that exhibits an industrial structure, in terms of clusters, very similar to the Greek one, and Germany, that represents a major supplier and market for many Greek industries. The other four nations analysed by Porter (1990), Japan, Korea, the UK and the USA, will be briefly examined.

Subsequently, Porter has applied his framework to a number of other countries. Particular mention will be made of the two most widely disseminated applications, the reports for Canada and New Zealand. These studies are again not critical of the framework, they are, however, interesting given the small size of the New Zealand market and the heated debate surrounding the Canadian case. Three attempts to test parts or all of the diamond framework will also be presented. These attempts are based on observations from New Zealand (as a complement to Porter’s analysis), Ireland (a small EU nation) and Turkey (a neighbouring country with a similar industrial structure to Greece).

The first European nation mentioned by Porter (1990: 307–331), as a post-World War II winner, is Switzerland. Switzerland was competitive in a wide array of manufacturing and service industries. Natural resources were little related to Switzerland’s success, as Porter (1990: 318) considers only the available hydropower and the pleasant landscape as advantages. Location and political neutrality had been much more important as was a highly educated and skilled pool of human resources. Low interest rates and easily available capital, along with a world-class transportation infrastructure, complete the picture for basic factors. These factors were upgraded through the educational system and the well-developed apprenticeship system, as well as the extensive in-house training of employees....