![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Patterns and Explanations

Asian communist countries demonstrated a different pattern of transition that was characterized by gradual, experimental, phased and partial reform as compared to the former communist countries in Russia and Eastern Europe that were illustrative of a "neoclassical" big bang or radical approach. The debate between shock-therapists and gradualists has dominated professional discussions on transitions from communism throughout the 1990s. On one hand, the proponents of the big bang approach argue for a quick and simultaneous introduction of all reforms. Works by authors in this category include David Lipton and Jeffrey Sachs, Anders Aslund, Andrew Berg and Jeffrey Sachs, Kevin Murphy et al., Jeffrey Sachs, Roman Frydman and Andrzej Rapaczynski, Wing Thye Woo, Jeffrey Sachs and Wing Thye Woo.1 On the other hand, those who favor a more gradualist approach emphasize the sequencing of multi-stage reforms and the virtues of gradualism. Works by authors in that category include Richard Portes, Ronald McKinnon, Gerard Roland, Mathias Dewatripont and Gerard Roland, John McMillan and Barry Naughton, Peter Murrell, John Litwack and Yingyi Qian, Philippe Aghion and Oliver Jean Blanchard, and Shang-Jin Wei.2 The ultimate intellectual difference between the two schools of thought lies in the extent to which each school accepts the validity of neoclassical economics in guiding the economic reforms and each school recognizes the role of political factors in economic policymaking. This difference in faith in neoclassical economics has influenced every debate in economic policy in the 20th century, and the debate between the two schools is unlikely to result in final agreement soon.3

The experience of the early 1990s was that big-bang approaches in Eastern Europe were painful, leading to unexpectedly large and persistent reductions in output growth after the radical departure and transition from state socialism, while gradualist approaches in Asian communist and post-communist states were surprisingly successful, leading to significant accelerations in output growth, except North Korea.4 Nonetheless, the North Korean economy has revived in positive growth, particularly since it adopted more open and liberal economic policies since the late 1990s, even though it has been crippled by very unfavorable external conditions and constraints. To provide readers with a visual picture of the five communist and post-communist states in East and Southeast Asia, a map of their relative geographical locations and basic statistics of economic development are presented (see Map 1.1 and Table 1.1).

Map 1.1 China, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia

Table 1.1 Statistics of five communist/post-communist countries (2005)

However, both theoretical and empirical work "has not established the superiority of one course of reform over another... There are cases where fast and gradual reformers have succeeded and where they have failed."5 Therefore, the debate remains controversial and inconclusive in the literature. To learn some valuable lessons about the choice of reform strategy from the different patterns of transition, it is useful to put the Asian transition in a broader comparative context in which transition has taken place across the two regions. China is often cited as the leading example of a successful gradualist approach to transition from communism. Some smaller Asian communist countries such as Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and North Korea have also adopted the similar gradualist approach. The key features of the Chinese model or the gradualist approach were an initial emphasis on agricultural reform and a gradual opening of the previously closed economy.6 Asian communist states have by and large followed a similar strategy of transition, which resulted in a similar pattern of transition, which can be compared to the shock-therapist approach in Russia and Eastern Europe (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Comparisons of gradualist and shock-therapist approaches

| | Gradualist Approaches7 | Shock-therapist Approaches8 |

| Characteristics | An initial emphasis on agricultural reform and a gradual opening of the previously closed economy; Reforms were partial, incremental, and often experimental; caused no initial downturn and avoided declining incomes and high unemployment; made no use of large scale privatization; gradually reformed prices and trade control; maintained exchange controls; and adopted active state industrial policy while maintaining the party-state control | An all-out approach to replacing the traditional central planning economy with a market economy in a single burst of reforms; a rapid, all-out program including as many reforms as possible in the shortest possible time; caused initial economic downturn, declining incomes, and high unemployment; made use of mass privatization of SOEs through voucher or sale-out programs; rapidly lifting state control over the major factors of production and exchange while maintaining minimal macro-economic control |

| Outcomes | The result of such gradual or incremental changes is that these Asian countries continue to remain Leninist one-party states, embrace an eventual goal of communism, and move toward market socialism | The result of such rapid or radical changes is that Leninist one-party states and centrally planned command economy collapsed in Russia and East Europe and these countries move toward market capitalism |

The central question is why these Asian countries adopted a gradualist approach to their transition that was different from their counterparts in Eastern Europe. Some explanations have been offered to address this question. Most of these explanations focused on exogenous economic and political conditions or different economic structures prior to reform in Asian countries that differed from those prevailing in Russia and Eastern Europe.9

- Unlike Eastern Europe that was more industrialized and overly specialized in heavy industry, Asian communist countries were predominantly agrarian societies with a huge surplus rural labor force ready to develop some new economic sector to support the old sector.

- The trade shocks due to the collapse of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) were so enormous that trade within the former Soviet bloc was totally disrupted and a more radical approach to trade liberalization was imperative in these countries unlike in the early stages of Asian transition.

- The decline in the power of the Communist Party in most of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union was coupled with the weakening of centralized political control over the economy while the power of the Communist Party was strengthened as a result of economic growth and improvement of living standards in these Asian countries.

From this perspective, the pattern of transition was predetermined by the initial conditions or macroeconomic and structural differences between Eastern Europe and Asia and therefore no real lessons could be learned from the comparative experience of transition from communism. This explanation is well deduced from the structuralist approaches of transition theory.

Structuralist approaches place major emphasis on macro-level social conditions or socioeconomic and cultural prerequisites of transition, particularly the long-term influence of the level of economic development, industrialization, urbanization, education, social structures, political culture, the role of civil society, and other social conditions, because they assume that these macro-socioeconomic conditions can explain the causes, paths, and outcomes of transition.10

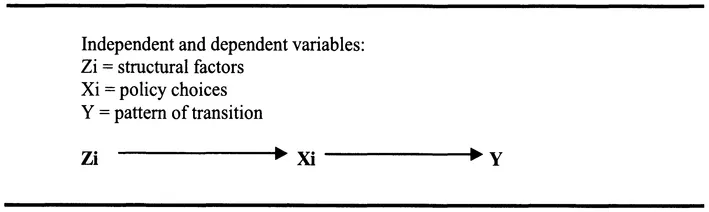

Structuralist approaches help us to understand why the old regime is challenged, threatened, or forced to reform, but can not tell us why and how the elites make the change in one way or another, in other words, why different countries take different approaches to transitions. Social and structural conditions may help to explain the dynamics of social change and transition, but they can hardly explain why different political actors make different choices, why their preferences change and policy choices shift from one to another, and why one choice prevails over another within the same social and structural context. Moreover, fundamentally flawed in these approaches is that the path of transition is predetermined by the initial conditions or macro-level economic and structural differences between Eastern Europe and Asia and therefore no lessons could be learned from comparative experiences. This is really deterministic. While initial conditions are important in determining and explaining why reforms are adopted, elite strategic policy choices best explain how reforms have been carried out, because it is elite strategic interactions and policy choices that have played a direct role in shaping the pattern of transition while structural factors an indirect one. Initial conditions, elite policy choices, and the pattern of transition should look like a set of antecedent causal relationships between z, x and y (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Causal relationship between Z, X, and Y

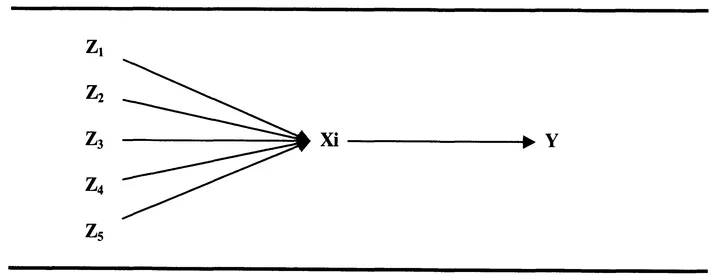

The initial conditions or antecedent causes of transition may differ significantly in different countries. However, these different pre-reform conditions or antecedent causes (such as predominantly agrarian societies, deepening economic recession or trade and financial difficulties) could prompt a common response or policy choice if the communist elite in the different countries shares a common belief in the efficacy of that response or policy choice, for example, the leadership's perception of the necessity for economic growth on one hand and the need for maintenance of communist power and preservation of party-state interests on the other. Just as individuals may take the same medicine to cure different physical problems, these countries may simultaneously choose similar reform policies to cope with different sets of political and economic problems. In this case, the specific antecedent causes (Z1, Z2, Z3, Z4, Z5) in different countries prompt the leadership to act on a common set of policy choices, Xi, to produce a similar pattern of transition, Y (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Explanation of the pattern of transition

In either case, the choice of similar reform policies, X, in coping with their economic and political problems (pre-reform conditions), produces a similar pattern of transition in these countries that is different from that of Eastern Europe. This analytical model of explanation is well deduced from the theoretical approach of strategic choice.

- Strategic choice approaches concentrate on the micro-level critical role of political elites and the interaction of their strategic choices, the splits within the old regime, the compromise or "negotiated agreements" between the "softliners" and "hardliners" on policy choices, and the process of transition.

- Strategic choice approaches emphasize the autonomy of elite strategic choices and political processes rather than the initial conditions and socioeconomic determinants of political and economic change, because elite calculations and preferences, strategic choices, and the interaction between the choices are viewed as decisive in determining paths and outcomes of transition though they do not deny the importance of economic factors.11

- Recent economics literature on the political economy of reform recognizes the critical role of political constraints, such as conflict of political ideologies, political resistance, political support, political acceptability and sustainability, asymmetric information, uncertainty regarding the outcome o...