The Forgotten POW Camp

What images does the name “Sandakan” evoke for the Japanese? Many know of it as a place somewhere on Borneo, yet few know of its exact location. Some know of it through Yamazaki Tomoko’s novel Sandakan Hachiban Shōkan (Sandakan Brothel Number Eight), a story (also made into a film) about the military brothels located there and the Japanese women—the karayuki-san, or “women travelers”—who worked there. In World War II, Sandakan was a key strategic point that linked the oil fields of the east coast of Borneo to the Philippines and to the whole of the Japanese-occupied Asia-Pacific. It also contained a large POW camp.

Few people outside Japan are familiar with the name “Sandakan,” and even in Australia fewer still know of the extraordinary events that occurred there. By September 1943 Sandakan POW camp held about 2,000 Australian POWs and 500 British POWs; only 6 survived to the end of the war—a survival rate of 0.24 percent. At Ambon POW camp 123 out of a total of 528 Australian POWs survived;1 in this case the survival rate was 23 percent. A total of 60,500 POWs worked on the construction of the Burma-Thailand railroad; about 12,000 died, a survival rate of more than 80 percent. Of the 9,500 Australian POWs who worked there, the survival rate was 72 percent—2,646 died.2 Of course, comparison of the survival rates should not overshadow the raw figures.

Construction of the Burma-Thailand railway and other such incidents have remained vivid memories in Australian history, yet Sandakan has been forgotten. Why is this so? It may be that the relatively large number of survivors of the more notorious incidents has ensured that many stories, memories, and publications circulated through the Australian community in the postwar years. The survivors of Sandakan were so few, and their experience was so extreme, that in some respects it is beyond telling. The psychological legacy is so overpowering that the remaining survivors find it difficult to talk about their experience at all. It was only in the early 1980s—when interviews were recorded with the survivors for an ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) radio program—that the name of Sandakan began to be heard.

Sandakan is similarly forgotten in Japan, though for a different reason. All of the guards at the Sandakan camp were Formosans (Taiwanese), under the command of Japanese officers, so there were few returnees to Japan who had any knowledge of the incident. And all documents relating to the camp were burned sometime toward the end of the war.

I conducted several interviews with surviving former Japanese military officers, soldiers, and Formosan guards who dealt with POWs in Sandakan. However, it was quite difficult to obtain honest accounts of their wartime experiences because of the nature of their inhumane acts against the POWs as well as the stigma attached to the label “war criminal.” In particular, Formosans are extremely reluctant to tell of their ordeal, first because of the shame about their own conduct in dealing with the POWs and second because of a deep mistrust of the Japanese, including me. These former Formosan guards regard themselves as victims rather than perpetrators of war crimes, much more so than the Japanese do. This seems to be quite natural since they did not voluntarily become POW guards but were forced to work for the Japanese forces. As a result, the amount of valuable information obtained through the interviews with the Japanese and Formosans was quite limited.

Yet the Sandakan incident provides the clearest picture possible of the relationship between the power structure of the Japanese army and the occurrence of war crimes. Warrant Officer William Stiepewich, one of the survivors of Sandakan, gave evidence at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal about the ill-treatment and ultimate massacre of POWs there. Stiepewich’s testimony, together with an affidavit from another survivor, Keith Botterill, ran to 109 pages.3 This testimony, the documents and transcripts from the B and C Class trials, and the interviews recorded for the ABC give us a fairly clear picture of the three-year ordeal of those who lived and died in Sandakan.4

Establishment of the Camp and the Labor Issue

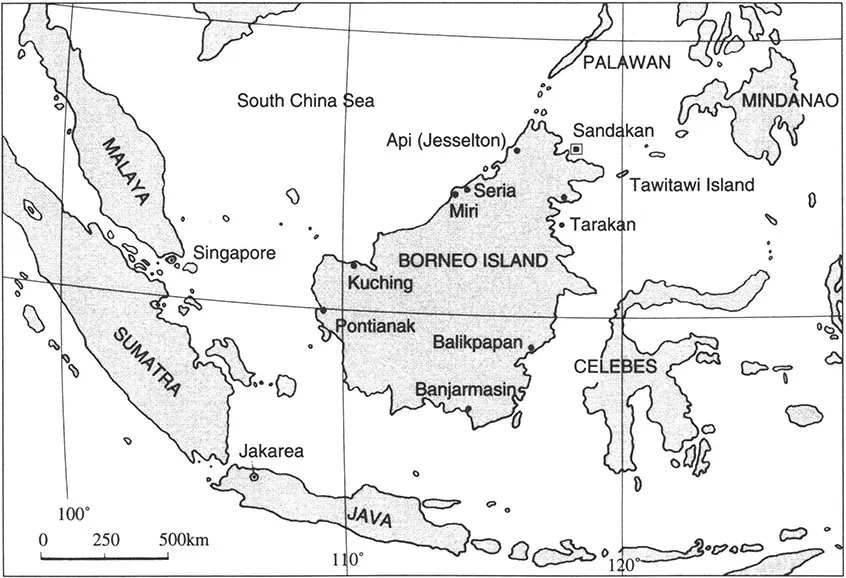

Prior to World War II Borneo was divided into two regions, Northwest Borneo, occupied by the British, and Southeast Borneo, which was a Dutch colony. The conquest of Borneo, Java, and Sumatra was a high priority for the Japanese forces, as the area had a number of major oil fields—Tarakan, Sangasanga, and Balikpapan on the east coast and Seria (now Brunei) and Miri on the west coast (Map 1.1). The destruction of Pearl Harbor and the siege of Singapore in late 1941 made it possible for an invasion force sailing from China to take these islands without fear of being outflanked by British Commonwealth forces, the South China Sea already being under the firm control of the Japanese forces. Seria and Miri oil fields and the refinery in Lutong were captured in mid-December, and on January 11, 1942, Japanese paratroops attacked Menado. Tarakan was taken on the fourteenth, Balikpapan on the twenty-third, and Pontianak, the largest city on the west coast, on the twenty-ninth. By the end of the month the whole of Borneo was in Japanese hands. The invasion force was followed in by the Oil Corps, a division of the Army composed of drafted engineers, who took over the operation of the oil fields and refineries from British and Dutch operators.5

The distance between the Philippines and Singapore (both of which had fallen to Japanese forces by early 1942) was too great for Japanese aircraft to fly in one stretch, and so it was decided there should be an airfield at Sandakan to provide a refueling point. The Sandakan airfield would also serve as a refueling point for aircraft en route to islands to the south, such as Java, the Celebes, and Timor.6 It was clear to the planners that construction of this airfield would require an enormous amount of forced labor. However, the Japanese forces had difficulty in gaining local laborers because most of them were mobilized for the construction of essential roads and military facilities in the Sandakan area at that time. Therefore, a POW camp was established at Sandakan for the purpose of exploiting the labor force of POWs. The Sandakan camp was established as a branch of the larger Kuching POW camp, the center of the Borneo POW camp network.

The notorious Changi camp in Singapore was used as a pool from which to draw POW labor. Changi held more than 50,000 prisoners, most of them British, Australian, and Indian men who had been captured in Singapore, Malaya, and Timor. From these prisoners a number of labor groups were formed. The first, A Force, consisting of 3,000 Australian POWs, was sent to South Burma in May 1942 and was mobilized to build an airfield there. These men were later sent to work on the Burma-Thailand railway. B Force, consisting of 1,494 POWs (145 officers, 312 NCOs, and 1,037 enlisted men) was sent to Sandakan.7 Some prisoners were conscripted into B Force by the Japanese, but the majority were prisoners who had volunteered for a work detail. They were not told by the Japanese what sort of work they would be given, but they were told that they would receive better rations and be located in a healthier environment than those who remained at Changi. B Force was moved from Changi in July 1942. By this time a number of Japanese war crimes had

already been committed against Allied POWs in other parts of the occupied Asia-Pacific. An example is the Bataan death march, which occurred in April 1942. About 16,000 Filipino and 2,000 American POWs, who had been captured during the fall of the Philippines, died after being forced to march 100 kilometers with little food and water.8 A Force had already commenced work in the extremely harsh conditions that were to become standard for POW labor, yet the prospective members of B Force knew nothing of these events.

POWs in all of the camps located in the Singapore area were obliged to take part in work details, but the work was not excessive and the treatment of prisoners by Japanese guards was relatively humane. (At this stage, prison guards were all Japanese. Conscripted Korean and Formosan guards were not used before May 1942.) But there were 50,000 prisoners in Changi, and they often went hungry. The opportunity to join a work detail, in which promised rations were relatively generous, must have been the major attraction for many.

Others might also have believed that their chances for escape would be greater in a smaller and more remote prison camp. Many found the atmosphere of Singapore—the city as well as the camps around it—extremely depressing. An air of humiliation and shame hung about the place. There were other, grisly reminders of death and defeat, such as the decapitated heads of Chinese and Indian civilians who had resisted Japanese rule, which were on display in the streets of the city and often seen by the prisoners when they were trucked from place to place on work details.9

The 1,500 members of B Force left Singapore in the 3,000-metric-ton Ubi Maru on July 7, 1942.10 Conditions were extremely uncomfortable. The Ubi Maru was a cargo ship, and the prisoners were camped on deck with no space to move around. They were also given little food and water throughout the journey. The ship took 10 days to reach Sandakan, sailing via Miri. During the voyage many of the prisoners noticed that the Ubi Maru had no naval escort and that relatively few guards or sailors were on board. This led to discussion of the possibility of taking over the ship by sheer force of numbers. Ultimately, however, it was decided by the ranking officers in B Force that it was “too early” to take over the ship and that the force should wait for a better opportunity for a mass escape to present itself. Subsequently, they were informed that a Japanese submarine had been following the ship at all times.11

B Force arrived in Sandakan on July 17 and was held 13 kilometers inland from the port, in what had previously been a British experimental farm. An internment camp had been built there by the British for Japanese residents of Borneo at the outbreak of the Pacific War. It had internment quarters with an intended holding capacity of 200, in which all 1,500 members of B Force were held. However, aside from the overcrowding, conditions were relatively good at first. The healthy POWs walked the 13 kilometers, and the POWs who were ill were ferried from the port to the camp by truck together with all heavy equipment.12

Several weeks after arrival in Sandakan, B Force was mobilized to build the airfield and the road that would be used to connect the airfield and the town. The original plan called for two landing strips each 850 meters long and 50 meters wide, which were completed in the first three months. But in order that large bomber-type planes could land, airstrips had to be extended to 1,400 meters long. Both ends of the 850-meter airstrips were valleys, and thus the extension work of filling up the valley was extremely hard.13 The prisoners left camp at 7:30 every morning and walked to the construction site eight kilometers away. They worked until 5:00 in the evening with a lunchbreak and even special rations, such as coffee, for those who had worked hard. There was no work on Sunday, so the prisoners usually held entertainment functions, such as a concert or a boxing match, on Saturday night. Prisoners received a small amount of pay, and there was a camp canteen from which they could purchase coconuts, turtle eggs, bananas, tobacco, and other goods.14 They also set up vegetable gardens within the camp. Thus, although the rations could not be said to be plentiful, they were at least sufficient for basic good health. Colonel Suga Tatsuji, the head of the POW camps in Borneo, appears to have been a relatively humane officer, as a number of events show. On the occasions when he visited the Sandakan camp, the prisoners’ rations would be improved (although they usually reverted to normal on his departure) by the prison officers, who must have presumed Suga would be impressed that the POWs were receiving relatively good rations (rather than the reverse). On another occasion he granted prisoners a three-day holiday, an extremely unusual act for a camp commandant. When he visited the civilian camp at Kuching, he would bring biscuits and other gifts and play with the children of the interned Commonwealth and Dutch families.15

It was not a war crime to put POWs to work, so long as they were paid. Article VI of an annex to the Hague Convention of 1907 (which was ratified by Japan) states that

The state may utilise the labour of prisoners of war Work done for the state is paid at the rates in force for work of similar kind done by soldiers of the national army, or, if there are none in force, at a rate according to the work executed. When work is for other branches of the public services, or for private persons, the conditions are settled in agreement with the military authorities.16

This article was further developed in Section 3 of the Geneva Convention (1929) governing work by prisoners of war. The Japanese government had signed the Geneva Convention but never ratified it because of strong opposition from the Japanese military.17 Soon after the Pacific War began, the Allied nations demanded that the Japanese government make a commitment to abide by the convention, a demand to which the Japanese government agreed.18 In accordance, the Japanese government enacted a regulation regarding POW wages in February 1942, which guaranteed wages for working POWs along the lines suggested by the convention. Further regulations of this sort were enacted regarding transport of POW labor (October 1942), treatment of POWs (April 1943), and work by POWs (May 1943). Overall, the content of these regulations was in line with the conditions set down by the two conventions.19

But one clause present in the convention articles regarding work by POWs was conspicuously absent from the Japanese regulations of 1943: the clause that prohibits putting POWs to work on projects directly connected to “the operations of war.” Furthermore, in May 1943 the Japanese government amended the October 1942 regulation regarding transport of POW labor to specify that the military was prepared to receive requests from vital industries—such as munitions or aircraft factories—for the supply of POWs as labor.20 The Japanese government went to great lengths to obscure the degree to which POWs were being used for war work. Yet the amendment cited clearly demonstrates that the use of POWs for war work was part of official policy.

Because of the discrepancy with the Geneva Convention and the complicated nature of the official Japanese position in relation to the convention, there was immediate conflict between the Allied POW officers and the Japanese camp commandants as to the legality of putting prisoners to work on the airfield. Australian officers complained to Captain Hoshijima Susumu, the commandant of Sandakan POW camp, and to Colonel Suga that putting prisoners to work on the airfield was a breach of international law. Both commandants told the Australians, untruthfully, that the airfield would be purely for commercial use.21 This lie was to become a major point of contention at the B and C Class trials held in Labuan after the war. However, both Hoshijima and Suga were caught in a bind, for the Japanese government did not formalize its guidelines for treatment of prisoners until the enactment of the 1943 regulations on POWs and work.22

In August 1942, when work on the airfield began, existing Japanese regulations contained no guide as to what types of work, if any, could not be undertaken with POW labor. Furthermore, individual initiative was not a highly regarded virtue within Japanese military culture, and middle-range Japanese officers were expected to follow closely and enact orders from higher authorities. It would have been completely out of military character for them to make their own interpretation of Japan’s relation to the Geneva Convention over and above the carrying out of their explicit military duty. In fact, the use of POWs as labor on military projects was not merely a common occurrence during the war; it was an important part of the overall war strategy and was explicitly ordered by Minister of Army General Tōjō Hideki in his July 1942 address to newly appointed POW camp commandants.23 Therefore, the final responsibility for this problem lies with the Japanese war leaders who refused to make explicit their divergence from the Geneva Convention on this matter or to create regulations that acknowledged their clear intention to use prisoners for military work. Instead they left a gray area, where the military imperative to use prisoners for war work was clear, but the regulatory framework within which this could legally occur remained obscure.

O...