eBook - ePub

Environmental Protection

Regulating For Results

Kenneth Chilton, Kenneth Chilton

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 192 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Environmental Protection

Regulating For Results

Kenneth Chilton, Kenneth Chilton

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This book presents a perspective on environmental regulation that is underreported in the national media. It addresses the need for environmental protection at two levels: analyses of ecological concerns and policy responses and general principles that apply to various environmental issues.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Environmental Protection un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Environmental Protection de Kenneth Chilton, Kenneth Chilton en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politica e relazioni internazionali y Politica. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part One

Key Concerns

1

Municipal Solid Waste Management and Myths

Kenneth Chilton

Trash—technically, municipal solid waste—is on the minds of nearly all Americans today. Most people are disturbed by televised reports of barges of garbage from New York on a worldwide search for a port to call home, medical wastes floating up on East Coast beaches, and tractor trailers that carry produce from the midwest to the east and return laden with garbage.

The public's concerns about waste disposal deserve a serious response. The problem of handling the nation's garbage is real and increasingly difficult to solve. Almost every important public issue, however, generates emotional responses. Within limits, this is helpful. Dramatic headlines arouse public support for change. But experience also tells us that there are important limits to the good that public outrage can do.

Workable solutions to complex issues do not arise from ten-second sound bites. Effective answers require a different approach—the less dramatic but equally essential step of careful analysis. To address the problem of properly managing America's municipal solid wastes, we must put our trash woes in proper perspective and match public policy to the critical components of the dilemma. In the process, it is necessary that several widely held myths be demolished and attention focused on the substantial issues, ones that cannot be placed readily on a bumper sticker.

Fighting Mythology

Myth #1: America Is Running Out of Landfill Space

What are some of the myths that are widely accepted about America's trash-disposal problem? First of all, most people believe this situation is a "crisis" because, supposedly, we are running out of safe landfill space. After all, 50 percent of the landfills in the United States will close in the next five years; 80 percent will close in twenty years.1 The specter of a significant portion of the 190 million tons of consumer trash expected to be disposed of in the year 2000 having no place to go is truly worrisome.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) surveys indeed do show landfill capacity declining dramatically over the next decade. There were 5,500 operating landfills processing 187 million tons of consumer and industrial solid wastes in 1988. Less than 2,200 of these sites will remain open in the year 2000, and they will be capable of handling only 76 million tons of trash a year.2

In addition, recent actions by state and local governments will accelerate the closure of substandard landfills. This is both good news and bad news: future landfilling practices will be more environmentally sound, but the cost of waste disposal will be substantially higher and a solid waste disposal capacity crunch will be that much more likely. Proposed EPA landfill guidelines will likely accelerate closings. These guidelines exempt landfill owners from costly closure and cleanup requirements if their facilities are shut down within one-and-a-half years of the adoption of the guidelines.3

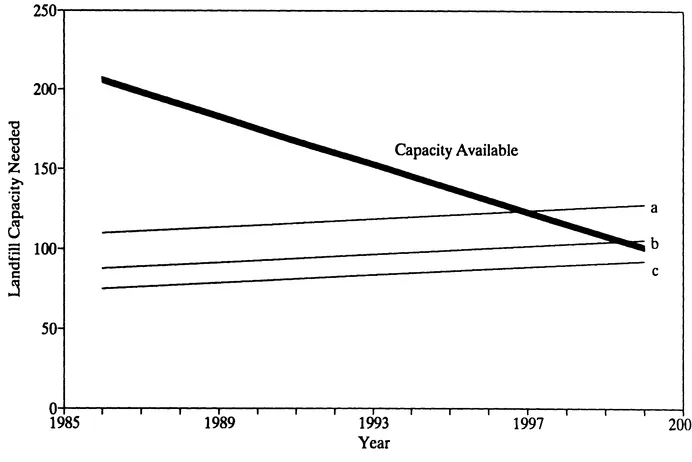

However, the fact that landfills close is not news. By design, most landfills remain open only 10 or 20 years. The landfill dilemma is caused by the paucity of new landfills. Current construction rates will add only about four million tons of new capacity a year. Figure 1.1 reflects the consequences of this greatly reduced rate of landfill siting. Depending upon the amount of recycling and combustion (incineration) being done, a capacity crisis could be expected as early as 1997 or as late as 2000.

Building safe landfills hardly requires space-age technology. The key requirements are systems to collect and process leachate—the liquid product of moisture seeping into the site combined with organic and chemical components stored there— and a method to collect and vent (or burn) methane gas generated by organic decomposition. Modern sites have a single- or double-composite liner or a liner of clay, a collection system, and pumps to send leachate to the surface for processing. They also have a system for monitoring and safely disposing of methane gas, often burning the gas to generate heat to be used by a nearby plant or public building.

FIGURE 1.1 The Impending Landfill Crunch (landfill capacity in millions of tons per year) a 15% of waste stream recycled; 15% of waste stream burned in resource recovery plants.

b 25% recycled; 25% resource recovery.

c 25% recycled; 35% resource recovery. Source: Landfill Capacity in the Year 2000 (Washington, D.C.: National Solid Wastes Management Association, 1989), p. 4. From 1986 EPA data.

Of course, not all locations are environmentally acceptable. A high water table or a porous subsurface would present serious leachate and groundwater-contamination problems. Long Island is not a desirable site for a landfill, for example, because of its high water table.

Yet, we are not running out of sites that are geologically suited for landfills. A recent environmental survey of less than half of the state of New York pinpointed potential sites totalling 200 square miles. In general, geologically acceptable sites abound in America.4

Landfills, even when made environmentally safe, are difficult to make desirable to the surrounding community. Thus, the siting of new facilities presents what economists term a public goods, or free-rider, problem. A large geographic area benefits from concentrating trash disposal at a relatively small site. However, the landfill lowers neighboring property values and causes affected citizens to oppose the facility. The observed Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) syndrome is not difficult to understand. Moreover, NIMBY naturally leads to LULU—charges that siting the landfill in the targeted area is "Locally Unacceptable Land Use." It is NIMBY that is the true impediment to siting, not a lack of technological expertise or safe geological sites.

Although the public goods problem is not new, the political potency of NIMBY and LULU is on the rise. In the early 1970s, municipal landfills were constructed at a rate of 300 to 400 a year. In the decade of the 1980s, this rate decreased to between 50 and 200 a year.5 Heightened environmental awareness has increased resistance to new landfills even while the environmental risk from these facilities has decreased significantly.

Myth #2: Americans Are Trash Junkies

Americans are admonished almost daily about their inordinate wastefulness. A typical U.S. citizen discards 3.5 pounds of garbage a day (1,300 pounds a year). U.S. consumers toss 1.6 billion pens, 2 billion razors and blades, and 16 billion disposable diapers into the trash every year.6

We are told that this wastefulness is far greater than our foreign counterparts and is a symptom of the "throw-away society" that ease-loving Americas have created. For example, an EPA report on solid waste notes that "an American generates approximately one pound per day more waste than his/her counterpart in West Germany."7 The Japanese recycle 40 percent of their municipal solid waste compared to our puny recycling rate of 13 percent.

What we are not told, however, is that municipal solid waste (MSW) data—foreign information and ours—are of uncertain quality. Most U.S. figures come from estimates of "materials flow" generated by a computer model written by Franklin Associates for the EPA. The EPA/Franklin model calculates the composition of MSW by weight, in terms of different materials and products in much the same way that economic activity can be broken down into industrial categories using input/output tables.8 The EPA/Franklin model estimates an average of 3.5 pounds of daily MSW per person in the United States. However, data from several landfill excavations indicate daily disposal rates of less than 3 pounds per person.9

Furthermore, the data quoted for daily solid waste disposal in other nations most often exclude recycled materials. When "net discards" are considered, the U.S. figure (according to the EPA/Franklin model) is about 3.2 pounds, for West Germany 2.6 pounds, Sweden 2.4, Switzerland 2.2 and Japan, a surprising 3.0 pounds. Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Hungary, New Zealand, and Korea have generation rates similar to the United States.10

Moreover, our "throw-away society" is not necessarily more wasteful than less-developed societies. According to Professor William Rathje, an archaeologist at Arizona State University who specializes in excavating landfills, "The average household in Mexico City produces one-third more garbage a day than does the average American household."11

Myth #3: Plastics Are the Problem

The leading villain in the municipal solid waste saga is the unnatural substance known as plastic. Plastic products shrink our landfill capacity by stubbornly refusing to biodegrade. According to some environmentalists, they also threaten our groundwater supplies and our ozone layer.

Plastic is ubiquitous. It is in disposable diapers and consumer packaging—beverage containers, microwave dinners, and shrink packs for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle toys. Worst of all, say the environmentalists, are polystyrene clam shells and beverage cups that are so popular with fast food outlets. Even the grocery stores have dared to replace the familiar brown grocery bag with thin, odd-looking plastic sacks.

One of the most interesting findings of Professor William Rathje and his "Garbage Project" is the lack of biodegradation in modern landfills. Perfectly preserved 30-year-old newspapers and ears of corn are typical of landfills in any climate. Each day's trash is covered with a layer of dirt to reduce odors, prevent runoff and discourage animal (and human) scavenging. As a result, biodegradation and photodegradation, which require sunlight, moisture and/or air, do not occur within the landfill except for yard wastes and other organic materials which degrade at a very slow rate.

Trying to make packaging "biodegradable" might have some benefits for reducing litter but may well be counterproductive for making landfills more environmentally sound. Biodegradable plastic often requires that more plastic be used to compensate for the loss in strength resulting from the use of a degeneration agent, such as cornstarch. Further, biodegradable plastics do not liquify. Totally degraded plastic is still plastic. The plastic has not disappeared, it has simply gone to pieces.

The fact that plastic does not biodegrade is not a sin; it is a virtue. Because it is inert, plastic does not release chemicals into streams or groundwater.

The grocery store that offers plastic bags instead of paper bags typically does so because the bags take less storage room. Given the lack of natural decomposition of paper in a landfill, it seems logical that plastic grocery sacks also take up less landfill space. Once again popular wisdom does not square with reality.

Furthermore, polystyrene—public enemy number one in the environmentalist's view—is not the threat that it is supposed to be. Its impact on stratospheric ozone depletion comes from the use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) as blowing agents in the production process, not from disposal of fast-food clam shell containers and coffee cups. Using CFCs as a blowing agent for production of polystyrene is being discontinued as a result of the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to phase out the production of CFCs. As for its role in wasting landfill capacity, studies indicate that all types of fast-food packaging combined comprise only 0.3 percent (by both weight and volume) of ma...