![]()

1

The due diligence process

Contents

The value of due diligence

Stages of the due diligence investigation

Negotiating a due diligence study period into a “deal”

Negotiation objectives

Negotiating the length of the study period

Negotiating physical access to the property

Negotiating access to pertinent property records

Negotiating the option to “stay or go”

Drafting the due diligence agreement

Beware of notice provisions

Sample due diligence study period agreement

Using the due diligence checklists

Bibliography

The value of due diligence

Within the real estate industry, “due diligence” is the term used to refer to a structured and comprehensive investigation of a real estate investment prior to its actual purchase, net-lease, or financing. Due diligence is the cornerstone of every successful real estate deal. Such investigations help investors select the most promising opportunities and filter out those deals which are best avoided. The investigation process collects qualitative and quantitative data about a property and its ownership history through primary and secondary research methods. During the due diligence period, the real estate investment is analyzed from a variety of perspectives so as to equalize what economists refer to as “information asymmetries” between the current property owner, who possesses the most information as to the quality of the asset, and the prospective purchaser or lender who enter the deal with little or no information about the property apart from what is easily observable. In his seminal work on the economic effects of asymmetric information, George Akerlof used the example of a used car transaction. The seller of a used car knows the vehicle’s maintenance and accident history, whereas the buyer cannot know from the price alone whether or not a used car is a “lemon.” Since the seller may be dishonest, the purchaser’s problem is to identify quality and distinguish good quality from bad quality (Akerlof, 1970).

While information imbalances are inherent to every commercial exchange, they pose a heightened degree of risk for parties to a commercial real estate transaction. As an investment asset class, commercial real estate is far more difficult to value than stocks and bonds. Real estate is fixed, heterogeneous, and illiquid. These characteristics limit the flow of available market price information. Furthermore, like a used car, a parcel of real estate may present hidden risks, some of which may actually be concealed by the current owner of the property. A visual inspection of a property by a prospective investor will provide some insights as to its physical condition, but cannot reveal a forged deed in the chain of title, environmentally contaminated soil, or a boundary line encroachment, for example. Yet each of these conditions may adversely affect the asset’s value. Similarly, a prospective investor must ferret out information as to whether a property under consideration is encumbered with any tax or mortgage liens, and whether zoning or land-use constraints would limit the property’s future development. For income-producing properties, existing tenancies pose both opportunities and risks. Lease provisions require analysis in order to project future cash flows and returns on an investment. As with a used car, the real estate investor’s problem is to identify quality real estate assets, and distinguish good quality from bad quality. It has been suggested that information asymmetries may be more important in real estate markets than in Akerlof’s classic example of the used car market (Garmaise & Moskowitz, 2003). The due diligence process is aimed at solving this problem. Its objectives are to confirm material facts about the property as provided by the seller (or the seller’s agent), and to uncover undisclosed potential financial and legal issues about the property that could impact value or expose the investor to risk. In addition to identifying legal and economic risks, a systematic due diligence investigation assists with the evaluation of a property’s potential to generate value through rental revenue and market appreciation.

For homebuyers, federal and state consumer protection laws have mitigated the harsh effects of the doctrine of caveat emptor, “let the buyer beware,” that has long applied to real estate acquisitions.1 For example, federal law requires all sellers of homes built before 1978 to disclose the presence of known lead-based paint and other hazards on the property using a form issued by the federal Environmental Protection Agency and they provide a government pamphlet on lead hazards. In addition, many states have adopted new home warranty acts that require developers of new homes to remedy major structural defects discovered by homebuyers within a specific time period after the closing of title. Further, most states have enacted real estate disclosure statutes that create a legal duty for sellers of one- to four-family homes to disclose (or at least, not conceal) known physical defects such as leaky roofs and potentially hazardous environmental conditions such as radon, mold or underground fuel oil-storage tanks. California’s residential real estate disclosure act is considered the most stringent in the US. In addition to disclosing known physical defects and malfunctions, the California law requires that property owners disclose a wide variety of possible risks, including the existence of any building settlement or soil compaction issues, any prior damage from fire, floods, earthquakes, and landslides, and whether appliances and fixtures are operable (Ca. Civ. Code § 1101 et seq.). These federal and state laws are designed to provide consumers with a contractual remedy against the seller in the event that residential real estate is sold with a substantial defect that was not properly disclosed.

For commercial real estate transactions, however, the doctrine of caveat emptor still applies. The general rule is that owners of office buildings, shopping centers, multifamily properties, and industrial property do not have any legal duty to disclose any information about the property to prospective purchasers, tenants, or lenders. It remains every commercial real estate investor’s obligation to verify key facts about a property and to discover potential risks posed by the real estate investment prior to “closing” the transaction. In the commercial arena, consumer protection laws do not protect disappointed investors from undisclosed property defects or unfair deals. Moreover, most commercial real estate is sold in “as-is” condition, with no seller warranties as to the property’s condition or fitness for the investor’s intended use. The law assumes that commercial real estate investors are sophisticated enough to know the importance of conducting reasonable investigations as to a property’s condition and value before acquiring an interest in a real estate asset. Those who fail to uncover defects and limitations relating to a property’s title, boundary lines, condition, permitted use, or development potential do so at their peril. In Futura Realty v. Lone Star Building Centers, for example, the buyer of environmentally contaminated land in Florida sued the seller of the land for fraudulent concealment. The buyer claimed the seller knew that the land was polluted and had a duty to disclose it because the pollution was not readily observable to the buyer. The state appeals court ruled that commercial real estate sellers have no duty of disclosure, noting that commercial property buyers may protect themselves through careful inspection of the property and price negotiation (Futura Realty v. Lone Star Building Centers, Fl. 1991; see also Jones v. Texaco, Inc., S.D. Tx. 1996). By conducting due diligence, the investor may avoid, or at least mitigate, real estate investment risks and resulting economic harm. Although commercial sellers are not under a legal duty to disclose, sellers may be willing and able to provide some representations about the seller’s ownership and authority to sell the property or other warranties about the property. Chapter 2 discusses warranties and covenants.

This book focuses on the legal aspects of real estate due diligence. It provides an analytical framework for the investigation of a variety of US real estate assets, ranging from undeveloped land to a single-family house or condo, multifamily apartment community, shopping center, office building, or industrial property. Equity investors are not the only parties interested in the due diligence process. Specified due diligence reports are required by lenders who finance commercial real estate in order to satisfy the underwriting requirements of secondary mortgage market credit rating agencies such as Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch, as well as government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This book includes legal due diligence issues typically investigated by lenders during the financing of a real estate transaction. Importantly, the value of a due diligence investigation is not limited to deal transactions such as sales, leases or mortgages. A comprehensive and systematic property investigation provides asset managers with key information on which to base recommendations for repositioning an asset in the marketplace or within an investment portfolio. For property managers, a due diligence investigation is a valuable approach to collecting information and data about new properties as they come under management. And, for real estate students, understanding the approach that investors take when evaluating the legal aspects of a real estate deal provides insights as to how seemingly archaic legal principles translate into practice.

Stages of the due diligence investigation

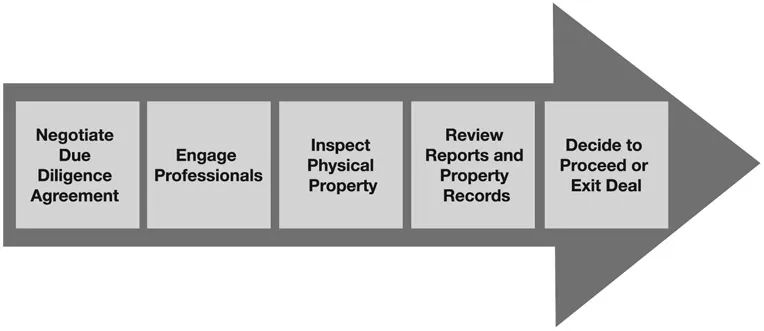

The necessity for due diligence arises whenever a real estate investor locates a property that appears to meet his or her investment criteria. Faced with obvious information asymmetries as to the quality of the investment, the investor must obtain physical access to the property to survey the property’s boundary lines and assess the integrity of the soil and any structures. A prudent investor also requires access to the owner’s title and property records in order to identify any legal or financial risks posed by the investment. Public land records must be searched to identify any mortgages, liens or other encumbrances recorded against the property. In addition, zoning and land-use entitlements for the property under consideration must also be analyzed.

For investors, the first stage of the due diligence process is negotiating access to the owner’s property and records—without becoming contractually bound to buy, lease or finance the property. This chapter describes how investors customarily negotiate access to a property and its business records, and identifies the practical business issues that must be resolved to arrive at a mutually agreeable understanding between the property owner and the investor. Once negotiated, a due diligence agreement may be included in a non-binding letter of intent, deal proposal, or other term sheet. Alternatively, the due diligence agreement can be included in a purchase option contract, which provides the investor with a right—but no obligation—to purchase the property during an agreed-upon option period. Finally, it could be incorporated as a contingency clause in a purchase and sale contract. Like any contract contingency, it must be satisfied before the contract is fully binding on the parties. A sample due diligence agreement is set out at the end of this chapter.

Once the investor and owner have hammered out a written agreement, the due diligence investigation begins. The investor receives and reviews the owner’s title and property records to confirm that the deal is as advertised, and to identify any economic or legal risks posed by the investment. For income-producing properties, the investor also analyzes current tenants and leases to project future cash flows. Depending on the complexity of the property under consideration, the investor engages one or more professionals to undertake land surveys, soil tests, and building inspections. Environmental assessments may also be required. This can be a time-consuming process because when real estate markets are strong, talented professionals are in high demand. Moreover, institutional lenders usually require borrowers to obtain engineering and environmental reports from the lender’s approved list of professionals. Accordingly, the best practice is to negotiate as long a due diligence study period as possible so as to permit ample time to secure the services of appropriate land surveyors, architects, engineers, and environmental consultants, to coordinate their access to the property, and for the professionals to produce reports of their findings before the end of the study period. In addition to reviewing the owner’s records and professional reports, the investors use the study period to review public records for mortgages, liens, easements, and other encumbrances that may be recorded or filed against the property. Commercial land title insurance companies provide title search services for this purpose. Zoning and land-use entitlements are also investigated and considered, particularly if the property under consideration is being acquired for development or redevelopment.

Before the end of the due diligence period, the investor must analyze all of the data and make a decision as to whether to proceed with the transaction or reject the deal. Depending on the terms of the due diligence agreement that was negotiated between the investor and property owner, the investor may have absolute discretion to walk away from the deal for any reason. As explained later in this chapter, some purchase and sale contact due diligence contingency clauses limit the investor’s right to exit the deal on the receipt of adverse engineering or environmental reports, for example. The following sections of this chapter explain the due diligence negotiation process and identify common business issues that must be resolved to reach an agreement.

Figure 1.1 Stages of the due diligence investigation

Negotiating a due diligence study period into a “deal”

Given the importance of due diligence, how does an investor obtain access to the property and its records to conduct a full investigation prior to a sale, lease or financing? The best practice is to negotiate a due diligence “study period” as early as possible in a deal, preferably before the signing of a binding contract. The investor objective is to obtain the opportunity to “kick the tires” at the property before becoming contractually bound to complete the transaction. Generally speaking, this is accomplished by means of a written agreement between the property owner and the investor which is included in a pre-contract letter of intent (LOI), term sheet, or other deal proposal. Similarly...