![]()

1

Chapter

Introduction to Video Production

Video production has always been a field that offers both excitement and opportunities for creativity, leadership, and personal growth. The field attracts all kinds of people—artists, technicians, organizers, and problem solvers, to name just a few. The process of putting audio and video elements together into something that tells a coherent story is more difficult than many people realize, and it is often more rewarding than they expect. It sounds like a cliché to say that video production offers something for nearly everyone, but in fact it is true.

As a field, video production has always been subject to rapid change. Since it is so dependent on equipment, it is always evolving in new and transformative ways as technology makes the tools smaller, faster, lighter, more efficient, less expensive, and more capable. However, the changes that have taken place over the past decade have been remarkable even by the standards of an industry that is used to rapid innovation. These changes—which involve the development and use of digital-based equipment and the availability of fast electronic connections between video producers and consumers—have affected both the way video production is done and the way people are viewing video programming.

Digital technology is described in greater technical detail later in this chapter and in various places throughout the book. For now, let’s just say that it allows video and audio equipment to function more like—and be able to interact more effectively with—computers. Digital technology has also been the driving force in making various production equipment more capable and less expensive. This is perhaps nowhere better seen than in the area of smartphones, which today offer not only the ability to access the Internet, countless apps, and messaging capabilities, but also in many cases function as very capable video cameras. In fact, some of today’s smartphones can record video rivaling the quality of that shot by equipment that would have cost thousands of dollars several years ago. This kind of development has been mirrored throughout the industry, as low-cost, medium-cost, and high-cost video and audio equipment has gotten better, more accessible, and easier to use. In a modern video production facility, everything is digital—from the time the light images go into the camera until they are shown on a monitor, and from the time sound waves are picked up by a microphone until they are broadcast over a speaker. As you will see throughout the book, this all-digital workflow affects nearly every aspect of video production.

The increased availability of fast connections between video producers and consumers has created changes that are perhaps even more profound. These connections—available via physical wire links or wirelessly through the air—are fundamentally changing the way people access and consume video content. You now no longer need to have an actual television to watch video—you can do it on your computer, tablet, or smartphone. Increasingly, you needn’t even watch your video according to a television station or network’s schedule—you can watch your favorite program when you want, you can watch it over and over, and you can even “binge watch” an entire season of a show in one afternoon if you like. An increasing number of consumers are “cutting the cable”—cancelling their cable television subscriptions and instead using the Internet and streaming services such as Amazon and Netflix for their video viewing. The rise of these new content producers has created increased demand for new programming and, hence, increased demand for video production.

In addition, digital technology and fast connections have made the range of types of video greater than ever before. This refers not only to subject matter (drama, documentary, comedy, etc.) but also to the source of the video content and the level of production quality. Digital technology has in many ways democratized video production, providing average people with access to near-professional level tools. That means that more people are creating and sharing video online through sites like YouTube and Facebook and that you can access videos from a wide variety of different sources—not just television networks or movie studios. This video content may vary widely in production quality, but today’s consumer for the most part has learned to accept video that is perhaps somewhat poorly lit or that has some shaky camera shots as long as it is conveying something interesting. In fact, someone may spend two hours watching a multimillion-dollar movie on his or her laptop, then go directly to YouTube and watch a series of cat videos that cost almost nothing to create. As long as people find the content compelling, they will often overlook lapses in quality.

That is not to say, however, that you shouldn’t strive for quality no matter what level of video production you’re doing. There are basic concepts and aesthetic considerations common to virtually all levels of video production, such as how to focus or how to properly frame a shot. This book is designed to introduce you to those basic concepts and aesthetic considerations, providing a basic foundation for video production at any level. It concentrates on traditional, studio-based video production, but also acknowledges more informal production techniques as well. Video production is an exciting field. Whether you are putting together a video of your college graduation ceremony to upload to YouTube or directing a hit show for network TV, you will find that the art of combining audio and visual elements into a meaningful whole is a creative process that is both stimulating and rewarding. In video production, you must interact with people and equipment. The purpose of this book is to give you the skills to do both.

Types of Productions

Imagine yourself in a cable network TV studio directing a show where famous actors discuss their careers and films. Imagine yourself interviewing dignitaries in China to report on the growth of the Chinese economy. Imagine yourself on the sidelines at the Super Bowl, hand-holding a camera to capture comments from the winning coach. Imagine yourself editing shots of an emotional medical drama, building the tension in the story as you work. Imagine yourself producing a web-based show that goes viral and becomes a national sensation. Imagine yourself in Antarctica experimenting with various microphones to pick up the noises made by penguins.

The above examples are just a sampling of the many ways to produce and classify video material. Video production can be divided into genre—drama, documentary, news, or reality, for example. It can be divided by its method of distribution—broadcast network TV, cable TV, satellite TV, or Internet. However, for the purposes of learning basic production techniques and disciplines, it is most useful to divide it in terms of studio production, field production, and remote production.

Studio production uses either a purpose-built studio or other controlled, indoor environment to produce video content. The studio will also be accompanied by a control room, where video and audio shot in the studio are channeled and mixed. News programs, game shows, talk shows, morning information programs, situation comedies, and soap operas are a few of the program types that are generally shot in a studio. Field production takes place outside of a controlled studio environment, venturing into the “real world” to gather footage. While field production offers less control over the shooting environment, it allows a broader range of scenes to be captured. Documentaries and dramas are shot primarily using field production, and many studio productions may also contain material shot through field production: interviews with witnesses of a robbery that are included in a newscast, the scene at an airport filmed for a soap opera, or footage of vegetables being grown on a farm used as part of a cooking show. Remote production is a combination of studio and field production. The control room is housed in a truck or set up temporarily in a designated area, and the “studio” is in the “field”; it might be a football stadium, a parade route, or an opera house.

Studio Production

Studio production is the main focus of this book, but many of the principles related to the studio apply equally well to field and remote production. The main difference is that field and remote production must take into account the technical problems created by the “real world,” such as rain, traffic noise, and unwanted shadows. The studio is a controlled environment specially designed for television production.

Figure 1.1A typical TV studio. (Courtesy of Shutterstock.)

The Studio

This section describes an ideal studio; the studio you use may not have all of these features, or it may have additional features. To begin with, a television studio is typically housed in a large room at least 20 feet by 30 feet without any posts obstructing its space. (See Figure 1.1.) Usually, a set occupies one end of the studio, and the cameras move around in the other space, but, if a studio is large enough, there may be several sets and the cameras move among them. The floor should be level, usually made of concrete covered with linoleum or another surface so camera movement is smooth. The ceiling should be 12 to 14 feet high to accommodate a pipe grid from which lights are hung.

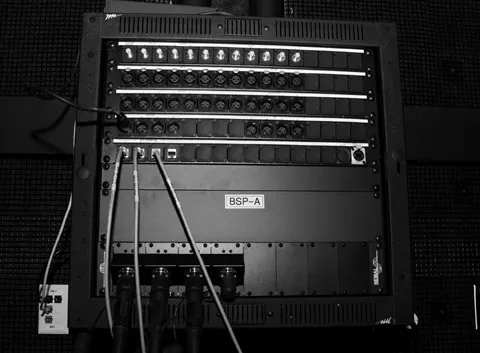

A studio is best located on the ground floor with large doors that open to the outside so set pieces and other objects can be brought in easily. Walls and ceilings should be soundproofed. The air-conditioning and ventilation systems need to be quiet so that the sound is not picked up by the microphones. Because lighting and other equipment require a lot of power, studios need to have access to much more electricity than the average room. Wall outlets must be provided not only for power but also to connect cameras, microphones, and other equipment to the control room, as shown in Figure 1.2.

Performers—who are often called talent—work in the television studio while one or more cameras pick up their images and microphones pick up the sound. Dedicated lights are usually necessary so that the cameras can pick up good images. Each camera’s shot is different so that the director, the person in charge of a studio production, can choose which shot to use.

A studio usually has TV sets called monitors that allow crew members and talent to see what is being shot. There is also a studio address loudspeaker system that personnel in the control room (see below) can use to talk to everyone in the studio, both talent and crew. This, of course, cannot be used during production because the microphones would pick up the sound as part of the program audio. That is why there is also an intercom system that allows various crew members to communicate with one another over headsets while a program is being recorded or aired. Many studios also have an IFB (interruptible foldback) system that enables control room personnel to talk to the talent, who wear small earpieces.

Figure 1.2 Connectors on the wall of a television studio allow video, audio, and other signals to be routed to the control room and other locations.

The Control Room

The control room, which is the operation center for the director and other crew members, is usually located near the studio. (See Figure 1.3.) It usually has a raised floor so the cables from the studio equipment can be connected to the appropriate pieces of equipment in the control room. Often, a window between the studio and control room allows those working in the control room to see what is happening in the studio. This window consists of two panes of glass, each of which is at a slightly sloped angle so that sounds do not reflect directly off the glass and create echo. The window should be well-sealed so sounds from the control room do not leak into the studio. Some control rooms, especially those used in teaching situations, have an area set aside for observers.

Figure 1.3 A TV control room.

The control room contains a great deal of equipment, which wi...